Covid is leading cause of death for police, so why are police unions still resisting the vaccine?

Last year was the deadliest period for law enforcement in nearly 100 years. But rising crime rates weren’t responsible for the roughly 458 officers who died in the line of duty in 2021 — Covid was.

For the second year running, the coronavirus was the leading cause of death for active-duty law enforcement, killing 301 people, according to a report from the National Law Enforcement Memorial and Museum released last week. That’s 65 per cent more Covid fatalities than 2020, likely a result of the highly contagious Delta and Omicron variants.

"This year’s statistics demonstrate that America’s front-line law enforcement officers continue to battle the deadly effects of the Covid-19 pandemic nationwide," the report reads.

Police officers receive hours of medical training. They’re called on to protect public safety. And they were among the earliest groups of people to get access to the vaccine. So why, in nearly every large police department around the country, are police unions fighting so hard to block Covid vaccine mandates?

The answer is a complicated mix of labour tensions and partisan politics, and goes back to the strange, singular position police unions occupy in American life.

Unions in major metro areas around the country have pushed back against mandatory vaccines for their officers, often via lawsuit, with arguments ranging from city officials skirting the official bargaining process, to questions about the efficacy of vaccines themselves.

Many unions have often framed vaccine mandates as a staffing issue: if police officers were forced to get the vaccine, they say, cops would leave in droves.

"We have to protect jobs. Whether it’s one or a couple hundred. That’s our mission here, to protect jobs. It’s not vaccinated versus unvaccinated," Mike Solan, president of the officers’ union in Seattle, told CNN. "It’s about the mandate in and of itself is a problem and they need to bargain this. Jobs are on the line. That’s our purpose as a union."

The department lost around 170 officers in 2021, with some thought to have left because of the Covid policy. In November, the police department was found to have the highest number of employees on leave because of the policy of any department in the city.

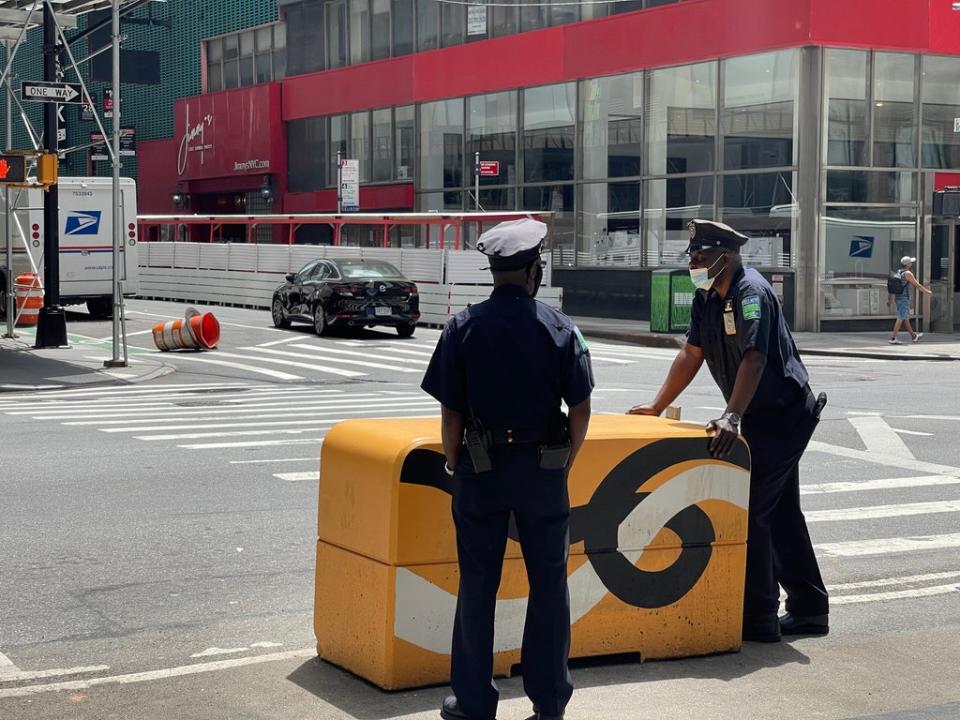

In New York, police unions warned of “chaos” if officers were forced to be vaccinated and sued the city over the “irrational” mandate, even though most of the NYPD’s roughly 36,000 officers have gotten the jab. Still, police unions there argued the city’s policies should do more to protect religious exemptions to vaccines, and should include an alternative for unvaccinated people who submit to regular testing, like the Biden administration’s proposed vaccine mandate. Nearly 7,000 officers have sought an exemption from the policy so far, according to the city’s Police Benevolent Association.

In Chicago, the former head of the city’s main police union died of Covid in October, and the current head of the Fraternal Order of Police has compared the vaccine mandate to Nazi Germany.

“This vaccine is not a vaccine. It is a COVID treatment at best,” said union chief John Catanzara, who got Covid himself, earlier this month. “Far too many people who are vaccinated are getting the virus for it to be called a vaccine. That needs to stop. All we can do is continue to distance a little better, wash your hands more, and be a little smarter about how you interact with other people.”

Last year, the city and the police union filed competing lawsuits and labour complaints against each other, with the police arguing the mandate wasn’t negotiated in good faith and forced officers who remained unvaccinated to pay for their Covid tests. The city, meanwhile, argued the union was encouraging its members to participate in an illegal strike and resist the new policy. Police crowd-funded nearly $300,000 for a “Hold The Line Hero’s Fund” to support officers whose pay had been cut off for refusing the new policy.

Last month, in St Paul, Minnesota, the police won a temporary restraining order on the city’s vaccine mandate. They argued they were “not anti-vaccine, nor are we conspiracy theorists,” but rather they saw the imposition of a vaccine mandate as a labour issue.

Mark Ross of the St Paul Police Federation told The Independent the department has been skilfully managing the pandemic since it began “without missing a beat,” implementing safety rules like masks, temperature checks, and prioritising answering calls when possible by phone or conducting interviews with witnesses outside, well before vaccines were available.

No St Paul police officer has died of Covid, he added, and about 80 per cent of union members are vaccinated. Given this track record, he says officers should be trusted to submit to testing if they don’t get the vaccine. Vaccines merely provide a “false sense of security” given the raging Omicron variant, he added.

“To lose even one officer to a Covid mandate that the city was going to implement without a testing option, would be far more dangerous to our community than someone that is unvaccinated and managing themselves correctly and takes steps to keep people safe,” he said. “It’s kind of a patronising thing to say to a cop, to a person who puts their life on the line.”

He also argued, bringing up a recent shooting that required multiple officers to respond, that community members don’t particularly care if officers are vaccinated.

“Not one person gives a rip if those officers responding to that shooting are vaccinated or not. Not even a question. Nobody cares,” he said.

This presumes, however, a level of community trust in police that may not exist in the Twin Cities, however. Following the police killings of Black men like Jamar Clark and Philando Castile, both St Paul and Minneapolis have seen massive racial justice protests for years against police brutality, well before those protests spread nationwide in 2020 after the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

Taken together, the nationwide controversy suggests something is clearly afoot in the nation’s police unions, who are perhaps the labour group most militantly resisting vaccine mandates, according to University of Minnesota labour historian William Jones.

“It’s odd that organisations designed to protect their members would be going so far out of their way to do something that clearly makes them vulnerable. That’s clearly a contradiction,” he says. “But it shouldn’t be. Police unions are undeniably conservative, in that they are really the only major unions that have allied themselves on the right side of the political spectrum.”

It’s been that way since the beginning. Police were only given union rights in the 1960s. Previously, one of the main roles of urban police forces was breaking up organised labour demonstrations and strikes on behalf of businesses, and officials fretted that if cops got the right to collectively bargain, they would sympathise with the working poor too much, or go on strike themselves.

That didn’t quite turn out to be the case. Once police in states across the country began winning the right to bargain in the late 1950s and 1960s, they quickly used their bargaining power to resist many reforms called for by the civil rights movement, which saw organised labour groups and racial justice protesters explicitly unite around causes like police brutality. In 1970s Philadelphia, the police union rallied behind Frank Rizzo, a former police commissioner known for his vehement opposition to racial integration, public housing, and explicit calls to “vote white.” In 1992, under the tenure of David Dinkins, New York City’s first Black mayor, thousands of off-duty police officers rioted around New York City Hall and occupied the Brooklyn Bridge at a union event called to protest his plan to create a civilian review board overseeing police misconduct.

”They very quickly mobilised to respond to that criticism, often allying themselves with mayors who really sort of invented the language of ‘law and order politics’ that Trump has claimed to represent,” Mr Jones added. “You get this emergency of a hyper-politicised police unionism that skews to the right in a way that police unions had not really been able to before. To a certain extent you’ve seen that since. We’re in a particular moment of a revival of that kind of politics.”

During his campaigns for president, Mr Trump actively courted police unions with his tough on crime message, winning the endorsement of hundreds of thousands of police officers across unions nationwide.

Over time, this militant relationship with outside oversight has hardened into a culture of insularity and embattledness, according to Marcia L McCormick, a professor at Saint Louis University School of Law who studies police unions. Residency requirements, strengthened police discipline, vaccine mandates — police unions have come to see all these as restrictions imposed by outsiders who cannot understand, let alone are not brave enough to carry out, police work.

“It is partly part of the culture of really reflexively resisting any changes that take away the autonomy of individual officers,” she told The Independent.

And unlike many other union leaders, Professor McCormick says, the American cultural veneration of police officers, particularly on the right, means that police union leaders are extremely visible in the media during political spats. You will scarcely see a pipe-fitter or dock-worker on Fox News, but police union officials are mainstays.

It’s an ironic reversal. During the 1980s, police unions were pushing extensively for personal protective equipment (PPE) out of fear of a new disease, the HIV/AIDs epidemic, with some unions arguing officers shouldn’t have to render medical aid at all to those suspected of being positive. One Playboy report from 1987 captured the dynamic of the time: a group of 20 Washington DC police officers raided a gay bar, wearing masks, gloves, and bullet-proof vests.

But it’s not just officers who are affected by police vaccine mandates. It’s the people they serve, Ms McCormick adds, people who don’t have a powerful union looking after their interests and getting booked on cable news. As officers and critics alike will note, police can’t do their job from behind a desk. They interact with people, often vulnerable ones, each and every day.

“If the officer’s health is at risk, the officer can take care of themselves,” she said. “There just isn’t the same kind of acknowledgement that the officers might be posing risks to people they’re pulling over or otherwise encountering. There hasn’t been as much focus on that.”

During a global pandemic, to “protect and serve” now means something new, more expansive. What that means to police unions is still a live question.