COVID: How medical professionals dealt with the unknown

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

ZANESVILLE − In late December 2019, the evening news began reporting about a mysterious virus in China.

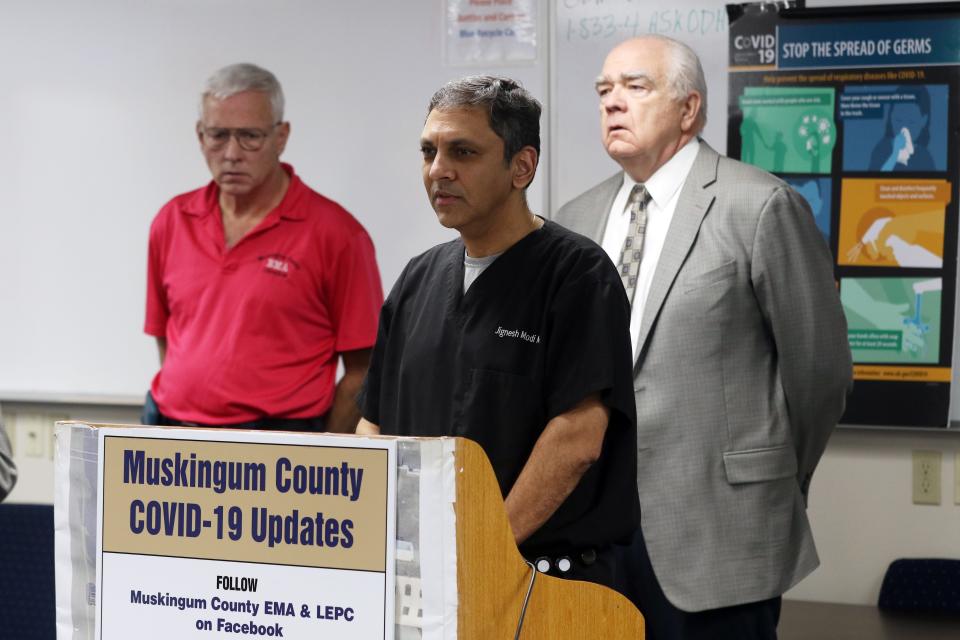

Dr. Jignesh Modi, who specializes in infectious diseases at Genesis HealthCare, said he knew early on that COVID-19 would be a problem, and, because of the way viruses spread, it would only be a matter of time before it appeared locally.

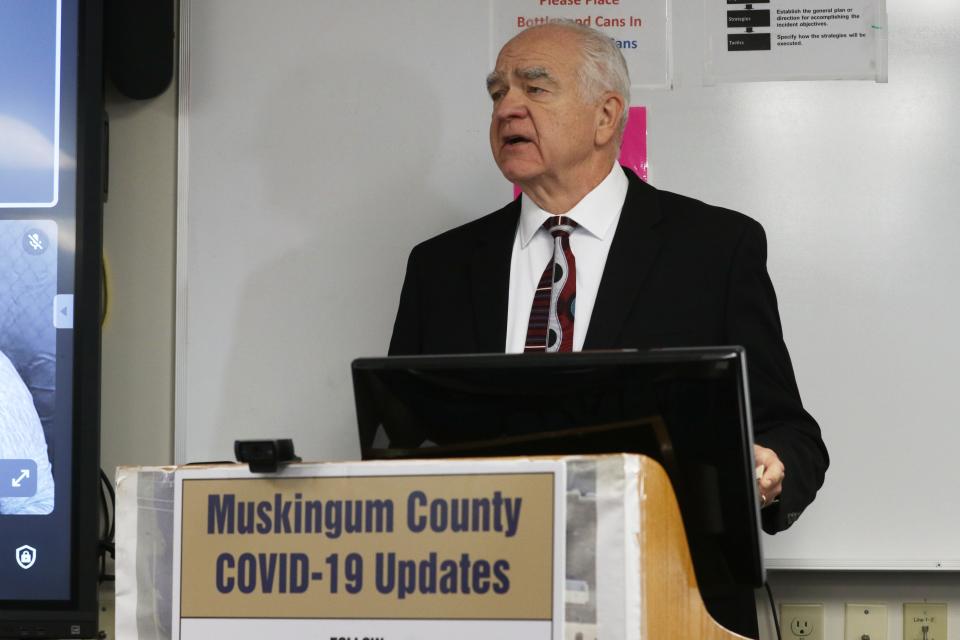

Chief Medical Officer of the Zanesville-Muskingum County Health Department Dr. Jack Butterfield said he remembered having discussions with Genesis Chief Medical Affairs Officer Dr. Daniel Scheerer in late December. "What is that thing, where did it come from?" Butterfield remembers asking. Much more urgent discussions followed by mid-January 2020 as the disease spread, the first case of COVID-19 in the United States was diagnosed that month.

An avalanche of death followed. According to the Centers for Disease Control, more than 350,000 Americans died of the disease that year, enough to lower the country's life expectancy by nearly two years.

Genesis Chief Medical Officer Scott Wenger remembers a case that appeared to be COVID-19 arriving at the hospital, and trying to figure out how to treat it. As so little was known about the disease, they feared it would wipe out the hospital. It turned out the patient didn't have COVID-19, but the first case would arrive soon enough.

On March 9, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine declared a state of emergency, after the state's first three cases of COVID-19 were reported in Cuyahoga County. By mid-March Ohio's restaurant dining rooms were closed due to the spread of the virus. Schools closed next and then on March 23 DeWine issued a stay-at-home order. The state's unemployment rate rocketed up to nearly 18% as non-essential businesses closed.

The first case of COVID-19 in Muskingum County was reported on March 25, 2020.

"When you get the first patient, something changes, it becomes real," Wegner said. "The first patient ended up in the ICU and on the ventilator and it go real, real fast."

There was a lull during the summer, then a massive surge in cases and deaths hit Muskingum and surrounding counties. Genesis Hospital began to fill up, then waned as the winter broke and warm weather sent people outdoors. But in October 2021 and into early 2022, the health care system was pushed nearly to the breaking point.

"We were cancelling surgeries because we didn't have the capacity," Wegner said. "It was the only time in my medical career I have ever had to sit in a room and say we are not going to deliver care to somebody because we don't have the resources."

"That has never happened to me before and I hope it never happens again," he said.

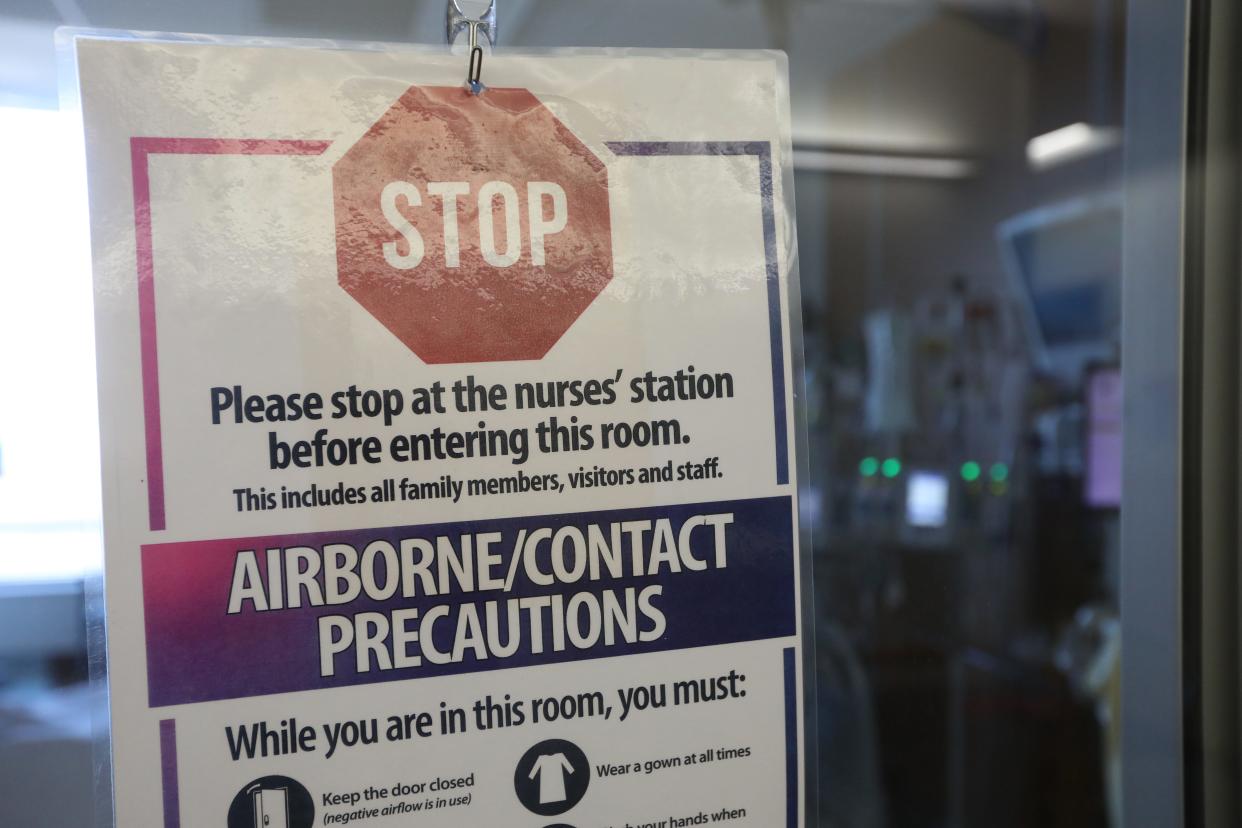

"Things held together, but it was stretched," Modi said. "We came across things we have never seen in this country. It still has repercussions because we still have shortages of things." Early on in the pandemic, masks and personal protective equipment were in short supply, which was well publicized, but also some medications, which the public never heard about, Modi said.

"Resource limitation has never been something you'd ever have to consider in this country," Wegner said.

Hospital capacity was also hit hard by the disease's impact on the workforce. "Nationally we save waves of people getting out of health care, and we are still struggling to meet those gaps," Wegner said. The impact was increased by who was leaving the field; the most experienced personnel.

Something never seen before

"We were faced with something no one alive had ever faced before, and that was a world-wide pandemic," Butterfield said. "And we didn't know what we didn't know. Data was coming in from 1,000s of sources daily, and the CDC was trying to ferret out significant data from false data, which can be very challenging.

"We didn't know what this was, yet we saw people dying by the thousands." There was no easy way to test for the disease available, Butterfield said.

"Guidelines were developed in an effort to save lives when you didn't know that the fatality rate across the board was less than 1%, when we saw 1,000s and 1,000s of people dying and tractor trailers set up as morgues, it looked like Ebola."

Ebola had very high fatality rate, and Butterfield said officials pictured half the county's population dying from the disease.

Wegner said should the world face another pandemic, he hopes that officials will do a better job of explaining what is known about the disease, and what is not.

"In an attempt to keep the public informed but calm, there was a hesitancy by the main governmental authorities, the CDC, to be willing to say what we don't know," Butterfield said.

Instead, medical authorities should have explained what was known, but also what needed to be known, and what information their recommendations were based off of. The messaging should have included the fact that recommendations, like masking and sanitation, were based on what wasn't known as well. "We have to be completely transparent in what we know, and what we don't know," Butterfield said.

"Here is what we think, this may change," Wegner said by way of an example. Early in the COVID-19 pandemic "an expert would stand up and say this absolutely what everybody has to do and then the message would change, and I think that lead to an erosion of trust," Wegner said.

Early in the pandemic, medical officials downplayed the effectiveness of masks, based on what was known at the time, Butterfield said. "As new data came out, and refined how masks can be effective, they were accused of backtracking. They were trying to make decisions based on the best data they had at the time.

"The public doesn't really understand how medical science works, or we wouldn't have all of the internet experts out there telling us what we did wrong," Butterfield said.

As the pandemic raged, better data emerged, and the best mitigation efforts followed. Misinformation began to emerge as well.

"There was a lot of misinformation, I don't know if agenda is the right word, but people weren't seeking the truth," Modi said. "For the most part, they still aren't."

The damage from misinformation has been immeasurable, Butterfield said.

"Vaccine uptake was destroyed by (misinformation)," Wegner said. "Unwillingness for parents to vaccinate for other conditions has risen," leading to pockets of long-forgotten diseases emerging.

"In medicine, we don't see a lot of politics. This one stood out," Modi said. Wagner said the emergence of the HIV/AIDs epidemic in the early 1980s was similar.

COVID-19 is still out there, but its mutations have grown steadily less virulent over time. That means the virus has become less deadly but more infectious. Modi said people who are in the hospital with COVID are there for another procedure and just happen to test positive. On one day in early March nine people were in the hospital with COVID, all there for another procedure or ailment, and none of them required treatment. This a far cry from September 29, 2021, when 19 people were in the ICU, and 17 of those were on a ventilator. A total of 72 COVID patients were in the hospital that day.

"Coronaviruses have been around a long time and we would detect them on a test periodically, but they tend not to be particularly symptomatic," Modi said. For the virus to continue to spread, it has to evolve to be more contagious rather than more deadly. People who are sick tend to be sequestered, which means they won't spread the virus. If they die, they won't spread the virus. SARS-CoV-2, the official name for what became known as COVID-19, was a novel coronavirus, which means it had never been seen before. Early variations were the most deadly, but the Omicron variant was highly contagious, and the variant that threatened to swamp the health care system. Fortunately, Butterfield said, the current variants have descended from the Omicron variant, and thus far don't show any sign of becoming more deadly. "The evolutionary pressure is for more transmissibility and less virulence," Wegner said.

"That is not to say there couldn't be a random virulence mutation," he said, "but evolutionary pressure is the other way."

The most pernicious effect of the pandemic has been the reduction in vaccinations across the board, Wegner said. Modi points out that smallpox, a disease that has killed millions, was eliminated, and mumps, diphtheria and polio have been suppressed to the point they are rarely seen.

"There have been adverse effects of vaccines, and there will be, but looking at the big picture, there is no doubt vaccines changed the course of humanity the last 100 years," he said.

"It is a danger to assume that we are not going to have another pandemic in the future," Wegner said. "I think it is likely to happen." He said he hopes that rationality wins out over the culture of disinformation that formed around COVID-19.

This article originally appeared on Zanesville Times Recorder: COVID: How medical professionals dealt with the unknown