COVID: School has reopened in Haiti. But students, teachers are protesting on the streets

Two weeks after schools were ordered reopened in Haiti, classrooms around the country remain empty because teachers are refusing to come to work over back pay and poor working conditions amid the global COVID-19 pandemic.

It is unclear how many schools are in essence closed, but since schools officially resumed on Aug. 10 — with national exams first and classes starting a week later — sporadic protests by teachers and students alike have erupted in several cities including Gonaives, St. Marc and most recently Jacmel.

While teachers have taken to the streets with their demands, students have done the same to demand that teachers return to the classroom. Some public school students have gone as far as attacking fellow students at private institutions that are in session, to let out their frustrations.

On Tuesday, a clash in the southeastern town of Jacmel between police and a student protester, Joanès Dory, left human rights observers and a former minister of education horrified.

Men kouman sa pase nan peyim. Men kouman elèv kap batay pou sa chanje nan koze edikasyon rive mete ak polisye kap lite pou jere fanmi.

Bagay yo anpil. pic.twitter.com/APTICqko81— Deus Deronneth (@Deronneth_Deus) August 25, 2020

Two members of the Haiti National Police’s specialized Departmental Unit of Maintenance of Order, or UDMO, were videotaped punching Dory while dragging him down Avenue Baranquilla in the Saint-Cyr zone of Jacmel. Dory, who attends Lycée Pinchinat in Jacmel, was subsequently arrested and taken to the nearby police station.

“What happened this morning is totally unacceptable,” said Nesmy Manigat, who served as minister of education and professional training from April 2014 to April 2016. “In no country does this make any sense where you have police reacting like this when students are in the streets.”

A spokesman for the Haiti National Police did not return a call. Neither Haiti’s Minister of Education, Pierre Josué Agénor Cadet, nor a spokesman for the ministry responded to a text and email from the Miami Herald seeking comment.

The situation, says Manigat, is beyond the issue of teacher pay or closed classrooms. COVID-19, which temporarily shuttered schools, has only added to the inequality gap.

It’s not Big Bird. Meet Tilou and Lili in this Sesame Street-inspired Haiti series

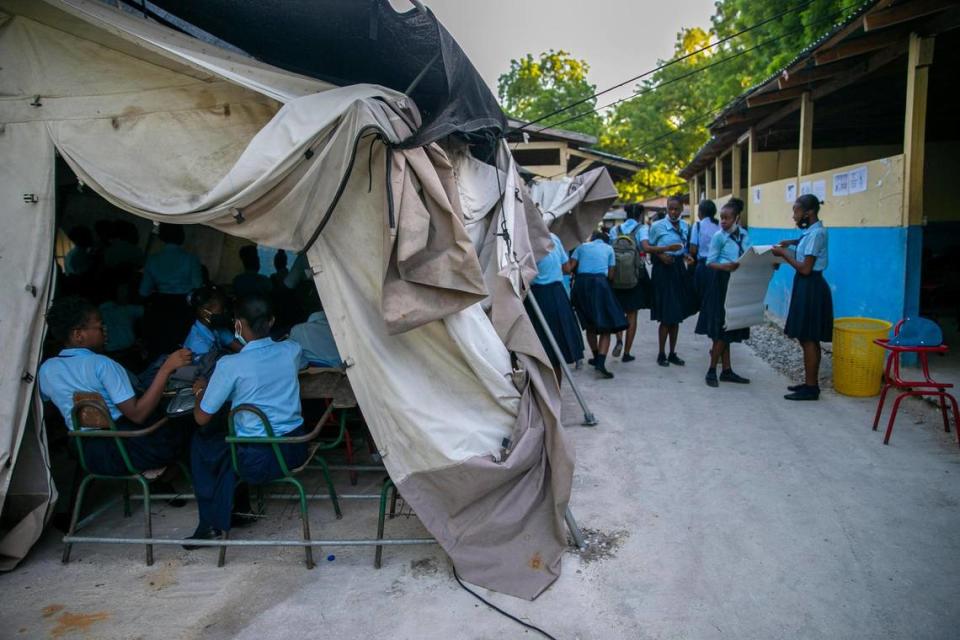

Even before the coronavirus pandemic forced the temporary closure of schools, education was already facing challenges. Parents spend about 80 percent of their income for schooling that is often lackluster, and mostly privatized with little government oversight. With education receiving about 11 percent of the national budget, the ministry struggles to not just give children a basic education but pay teachers on time and provide a bare minimum in terms of classrooms.

During the pandemic’s shutdown, children, who had already missed months of schooling last year due to violent anti-government protests, continued to fall behind because many lacked the technology or electricity or both for virtual learning. Students at wealthier schools were able to complete their studies and will return to classes on Sept. 7.

The reopening of most public and some private schools in early August was received with mixed reactions. Union leaders harshly criticized the decision, saying the government has not put in place the proper sanitary measures to help schools minimize transmission of the coronavirus, which continues to spread in the country.

“Some schools do not even have water,” said Magalie Georges, a career teacher and secretary general of the National Confederation of Educators of Haiti (CNEH). “They closed the schools in March when there were only two cases of COVID-19. Now they are opening it when there are thousands of cases. The health and security of the professors and students are in danger.”

Some Haitians abroad have tried to help. Fleur De Vie, a nonprofit education charity based in New York, recently contributed 5,000 masks for schoolchildren in 14 communities around the country. But the needs are much greater.

From uniforms to apps, transforming Haiti education, one reform at a time

In the city of Gonaives, just north of the capital, there are between 500 to 600 schools, only about 70 of them public. Though buckets of water have been provided for the classrooms, and students are wearing masks, a school director said social distancing is impossible in the classrooms, which are already overcrowded. He also said doing a teacher rotation schedule would require the government, which has been unable to meet teacher demands for pay increases or even back pay, to hire more teachers.

“Add to that the economic crisis and it means that teachers’ salaries don’t account for anything,” Georges said, noting that teachers’ pay has not kept up with the rising cost of living. “All we are asking is for these issues be addressed in order for schools to be open.”

After Georges went public with her criticism on Haitian radio earlier this month, she was abruptly transferred from Canape Vert to Croix-des-Bouquet, a suburb on the outskirts of the capital that is currently under attack by an armed gang.

Speaking to the Miami Herald on Tuesday, she accused the government of using “repression” to try to silence its critics, including students and teachers.

“Jacmel, St. Marc, is where the mobilization is strong, and everywhere where there are forceful protests is where the repression is strong,” she said, listing some of the cities that have been at the center of recent school-related protests.

On Tuesday, protests were reported in Jacmel and in Hinche, a city in the Central Plateau region.

During the Jacmel student protest, the specialized unit of the Haitian national police showed up and started firing tear gas at protesters.

A report from the National Human Rights Defense Network said that police refused to let anyone approach one of its observers, and that Dory, the student who was arrested, still in his school uniform, had a swollen lip and was in handcuffs.

‘It’s revolting,” Renan Hédouville, director of the National Office for the Protection of Citizens, said about the police response.

Dory and the other students, Hédouville said, have a right to exercise their right to an education and not have police react violently.

“The schools are open, but the children do not have teachers in the classrooms and they are demanding the right to an education,” Hédouville said. “We at the Office for the Protection of Citizens, who are responsible for promoting the protection of human rights, believe that the demands of the children are legitimate and we believe that the Ministry of Education should provide teachers with the means to do their jobs as educators.

“When a teacher hasn’t been paid in 10 months, 12 months, 15 months, it’s difficult for that teacher to do his or her job because they have children to send to school, and has a family to take care of,” he said. “The Ministry of Education has not assumed its responsibility and has decided to open schools without doing what was necessary for schools to reopen. ... He promised he would put water in the schools and there is no water; he promised masks and the children don’t really have masks. He promised he would pay the arrears of teachers and up to now there are a bunch of teachers who have not been paid.”

On Tuesday, the director of the Pan American Health Organization, Dr. Carissa Etienne, expressed concerns that across Latin America and the Caribbean, countries such as Haiti, which last month ended its emergency COVID-19 order, have gradually relaxed restrictions, resumed commerce and are gearing up to head back to school.

“In far too many places, there seems to be a real disconnect between the policies being implemented and what the epidemiological curves tell us,” Etienne said. “This is not a good sign. Wishing the virus away will not work. It will only lead to more cases, as we’ve seen over these past six weeks.”

As of Tuesday, Haiti had recorded 8,110 cases of COVID-19, and even with the country’s testing limitations, there are signs that the number of cases was beginning to increase. That concern only grew this week after Tropical Storm Laura left at least 20 people dead as it battered the country, washing out roads and bridges in cities like Jacmel.

Manigat, the former education minister, has for some time expressed concerns not just about the reopening of schools amid a global pandemic but leaders’ failure to properly finance education in the national budget.

With inflation around 23 percent annually and Haiti’s domestic currency depreciating, the average public school teacher, he said, is getting paid less than $120 a month. Some private school teachers make even less.

It’s only right, Manigat said, that the government address teacher salary demands over months of back pay and payment promised during the shutdown.

“There is a real problem here and it’s not just about whether to open schools or not, but there is a real lack of resources; education isn’t a priority for the authorities in the country,” he said.

Reopened public schools are scheduled to end the 2019-2020 school year in October and reopen on Nov. 9. Some private schools, mostly those that are well off and able to put in place distance learning, have been authorized to start the new school year in September.

“That doesn’t make any sense,” Manigat said. “For me, the government has created most of the problems we are living here today. It’s a total mess that we’re in.”