This COVID study has been tracking immunity for 3 years. Now it's running out of money

A long-running study into COVID-19 immunity has unearthed promising insights on the still-mysterious disease, one of its lead researchers says — but she's concerned its funding could soon dry up.

The Stop the Spread project, a collaboration by the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (OHRI) and the University of Ottawa, has been monitoring antibody responses to COVID-19 in hundreds of people since October 2020.

For the first 10 months of the project, about 1,000 people sent in monthly samples of their blood, saliva or sputum — a mixture of saliva and mucus — for analysis.

The researchers then winnowed that group to about 300 and kept following them as vaccines were developed and new variants emerged.

While there are other longitudinal COVID-19 studies underway, Stop the Spread is notable because it launched so early in the pandemic that some participants hadn't even fallen ill yet, said Dr. Angela Crawley, a cellular immunologist with OHRI and one of the project's co-investigators.

That gave them access to cells and plasma untouched by the COVID-19 virus — a unique baseline, Crawley said, from which they've since tracked changes in immune responses and antibody levels.

But with the pandemic approaching the four-year mark, she and other researchers worry enthusiasm to fund COVID-19 research like Stop the Spread is waning — and that could have implications for how Canada tackles future outbreaks.

"Research funding has dwindled, and, you know, things change," she said. "So a lot of what we've built is under threat of collapse."

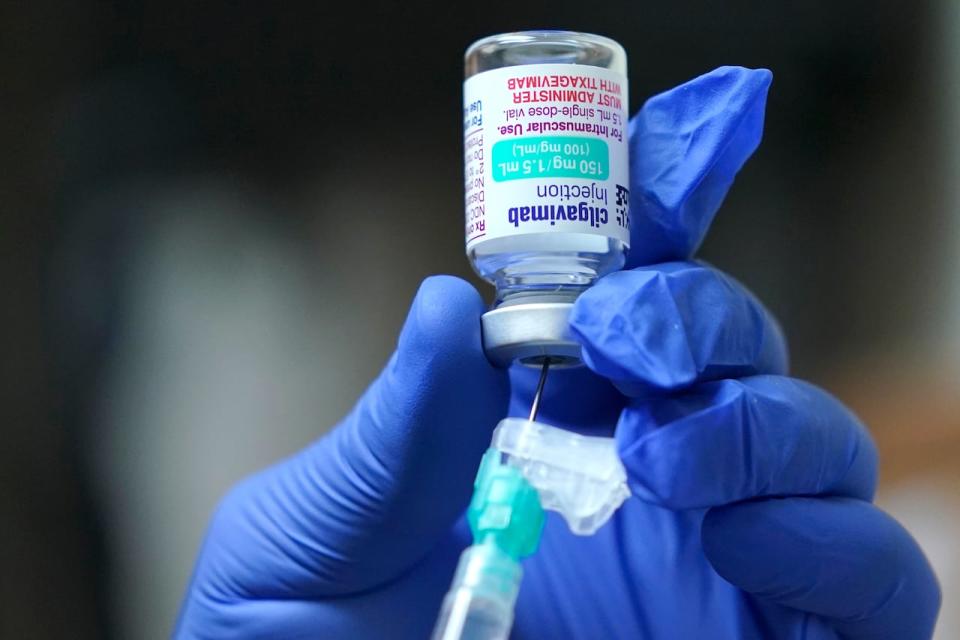

Stop the Spread is one of nearly 1,000 projects that has received funding from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, or CIHR, since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. (Associated Press/Ted Warren)

Sex and antibodies

Stop the Spread got roughly $2 million from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the country's health research granting agency, to follow that first 10-month cohort, and then leveraged that initial work to keep the money flowing for several more years.

During that time, and thanks in large part to advanced machine learning — a form of artificial intelligence that allows computers to adapt and draw inferences from data without explicitly being programmed to do so — the team teased out intriguing relationships from all the COVID-19 data in their hands.

For instance, Crawley said they've uncovered "pretty compelling" evidence of a link between one's sex and one's ability to generate and maintain antibodies.

Across all age categories, the data seems to suggest women are slower to shed antibodies than men, Crawley said. The distinction is sharpest in younger age groups, with rates of antibody loss gradually converging the older people get.

That sort of data, Crawley said, can help "fine-tune" future public health responses to COVID-19, which could include vaccines that better account for those differences in age and sex.

"How sophisticated our antibody response is relates to how well we can neutralize the virus," said Crawley. "We're not talking about protection against infection — that's a different conversation — but protection against disease severity, which means a lot when you talk about respiratory infections."

In addition to the CIHR funding, Stop the Spread also got money from the COVID-19 Immunity Task Force (CITF), which was established by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) in the pandemic's early days.

Its mandate is — among other things — to fund research into COVID-19 immunity that would help Canadian policymakers make "evidence-based decisions." According to PHAC, It's handed out nearly $230 million to support scientific endeavours since launching in 2020.

It's definitely a labour of love, but there's so much to learn from this. - Angela Crawley

But there's increasing worry among researchers who study COVID-19 that the overall pot of money is evaporating, said Dawn Bowdish, a professor at McMaster University and Canada Research Chair in Aging and Immunity.

"The number of outbreaks that we have for COVID is still disrupting care. It's still costing people their health and their lives," said Bowdish, who's been following more than 1,000 long-term care residents as part of her own COVID-19 research.

"But there's just no appetite to acknowledge that this is still a problem, and it's incredibly frustrating, because the work that we do applies to all sorts of different infections."

Christine and Jim Bonta, two longtime Stop the Spread participants, say a premature end to the study would mark a lost opportunity to learn more about pathogens like COVID-19. (Trevor Pritchard/CBC)

'Breaking our hearts'

The federal government has invested $430 million through CIHR into nearly 1,000 COVID-19 research projects since the start of the pandemic, said PHAC spokesperson André Gagnon.

The agency still acknowledges the virus "poses a grave health threat," Gagnon wrote in an email to CBC, with CIHR now home to a research centre focusing on pandemic preparedness and other health-care crises. And while it's still funding projects on topics such as COVID-19 misinformation and long COVID, it also "recognizes the need to shift funding priorities to respond to current events."

"[CIHR continues] to run 100+ funding competitions every year to invest research into other priority areas for people in Canada, such as cancer, heart disease, dementia, the opioid crisis and ways to strengthen Canada's health-care systems," he wrote.

The CITF, meanwhile, is slated to wrap up its work in March 2024, Gagnon added.

Bowdish says her research only has funding until the end of this year. Crawley, meanwhile, says Stop the Spread's CIHR funding is running out in March, and they're trying to stretch that out to follow a smaller cohort of about 100 people until mid-2025.

(Crawley is conducting parallel research into T-cells and immunity that's only funded through CITF until the end of this year. With all the work they have ahead, she says there's no way they'll get that done to her satisfaction.)

"It's literally breaking our hearts. We hope that we can find a way to sustain this for Canadians," she said.

Ending the Stop the Spread project would make for a missed opportunity, said participants Jim and Christine Bonta, who've been part of the cohort since 2020 and recently signed on to continue into 2024.

"It would be knowledge lost, in particular about the effects of long COVID," said Jim Bonta. "I don't have long COVID, but I guess I would be [part of] a comparison group."

"COVID is still circulating. And we don't know when this is going to go away, if it will go away, and what else is going to emerge," added Christine Bonta, a retired nurse.

"We need to be prepared to deal with that, [because] in 2020, we were not prepared."

Crawley says her team has uncovered 'pretty compelling' evidence suggesting a link between one's sex and one's ability to generate and maintain antibodies that fight the COVID-19 virus. That work is now being submitted to a 'high-impact journal,' she added. (Trevor Pritchard/CBC)

The ideal scenario

For Crawley, who's also director of the biobank for the CIHR-funded Coronavirus Variants Rapid Response Network (CoVaRR-Net), the ideal scenario would be to get stable funding to continue Stop the Spread beyond 2025 while also making that biobank truly national in scope.

That would mean a physical facility with samples stored in freezers, with back-end infrastructure that would allow other researchers across Canada to easily access the data and share their own findings.

All the contracts would be in place so that scientists, governments and industry could all get at that information — something that would "break down silos" in scientific research and foster collaboration, she said.

"When there's a pandemic, it's no longer about, how can my career advance?" said Crawley. "It shouldn't be like that. It should be, how can we all work together?"

Crawley also said her team has great respect for the Bontas and everyone else who's committed three-plus years of their lives to Stop the Spread.

They feel an almost "crushing responsibility," she added, to eke as much knowledge as possible out of the data they've collected — and continue to collect, at least for another year and a half.

"It's definitely a labour of love, but there's so much to learn from this," she said. "And we do feel a pretty strong responsibility to make sure that we can learn as much as possible."