COVID variants have been renamed to avoid ‘stigmatizing’ labels. Here’s what to know

It has been common practice to name new diseases based on where they emerged, such as the Middle East respiratory syndrome, or Zika virus, dubbed after a forest in Uganda.

But in recent years, public health officials have acknowledged that doing so fuels stigma and discrimination against those regions or people. Such negative impacts were clear when top figures, including former President Donald Trump, consistently referred to the coronavirus as the “Wuhan virus” or “China virus,” blaming the country and its people for the pandemic.

In February 2020, the World Health Organization officially named the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) and the disease it causes (COVID-19) to avoid “unintended consequences in terms of creating unnecessary fear for some populations, especially in Asia.”

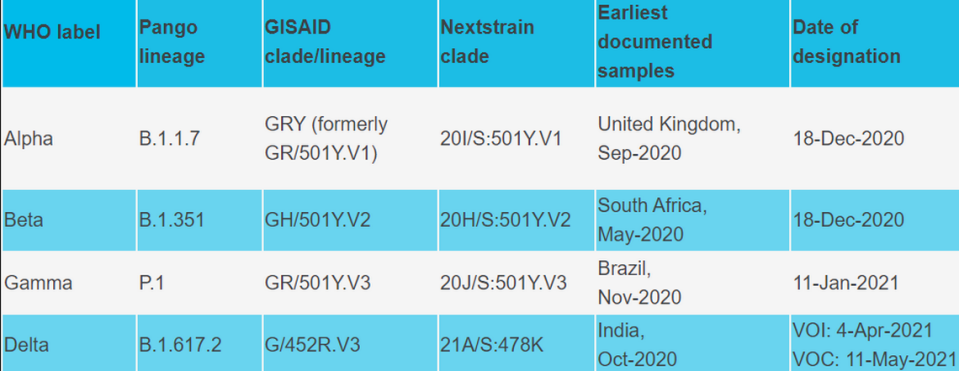

Now, the WHO has officially renamed the coronavirus “variants of concern” and “variants of interest” — previously labeled with a series of numbers and letters by scientists but mostly referred to by the public by the region it was first discovered — using letters of the Greek alphabet.

B.1.1.7, the variant that first emerged from the U.K., is now Alpha; B.1.351, the variant first discovered in South Africa, is now Beta; and so on.

The new naming system mirrors that of hurricanes after the 21-name rotating list is spent, like it was last year during a record-breaking season. Although as of this year, the Greek alphabet will no longer be used “because it creates a distraction from the communication of hazard and storm warnings and is potentially confusing,” the World Meteorological Organization said.

The “simple, easy to say and remember” labels for the non-scientific community were selected by an international group of experts who are members of existing naming systems, knowledgeable on virus classification, researchers and national authorities, according to the WHO. It’s unclear if the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — the national public health agency of the U.S. — will encourage the new names, too.

Previous labels for the coronavirus variants will not be replaced, but will continue to be used in research.

“While they have their advantages, these scientific names can be difficult to say and recall, and are prone to misreporting. As a result, people often resort to calling variants by the places where they are detected, which is stigmatizing and discriminatory,” the WHO said. “To avoid this and to simplify public communications, WHO encourages national authorities, media outlets and others to adopt these new labels.”

Asian people still suffering from discrimination, hate crimes

Despite an early renaming of the coronavirus and the disease it causes by WHO officials last year, Asian people from all over the world have been targets of discrimination and xenophobic attacks since the pandemic began.

Hate crimes against Asian people continue to occur and have seen recent spikes in the U.S., particularly after a March 16 series of mass shootings at three spas or massage parlors in Atlanta that killed eight people, six of whom were Asian women.

President Joe Biden signed a COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act into law on May 20 that emphasizes the increase in violence against Asian Americans. The legislation helps make state and local hate crime information more accessible to the public.

“This behavior, and the stigma associated with referring to an illness in a way that deliberately creates unconscious (or conscious) bias, can keep people from getting care they may desperately need to get better and prevent others from getting sick,” Dr. Marietta Vazquez, vice chair of diversity, equity and inclusion for pediatrics at Yale School of Medicine, wrote last year.

“When faced with this type of constant, heightened discrimination our friends, neighbors and colleagues of Asian-decent can feel uncomfortable in places they should feel welcome, included and safe,” Vazquez added. “This type of discrimination may also put their mental health at risk.

“Pathogens do not discriminate.”