We Crash Four Cars Repeatedly to Test the Latest Automatic Braking Safety Systems

The kick-drum thump of a harmless 30-mph shunt into an inflatable faux car rouses the same visceral remorse as a real car crash. The stomach knots with nausea. Mortification burns deep in every muscle. Within seconds, the brain catalogs the near trauma under Things That Should Not Be Repeated, right next to beer pong played with Captain Morgan.

Against our instincts, we keep taking runs at the balloon car. We nudge, punch, and plow into the generic air-filled Volkswagen again and again and again, not unlike American drivers, who, in 2016, drove into the back ends of other vehicles 2.4 million times. The rear-end collision is America's favorite way to bend sheetmetal, accounting for nearly one-third of all crashes.

But for every hit in our testing, there are several more kamikaze runs where the test car shudders to a halt just inches from the half-a-car punching bag. This is the work of automated emergency braking (AEB), which can detect an imminent rear-end collision and apply the brakes to mitigate or prevent the impact. Twenty automakers, whose products account for 99 percent of all new-vehicle sales in the U.S., have agreed to equip their full lineups of cars, SUVs, and light-duty trucks with AEB by 2022. But you don't have to wait. AEB is already ubiquitous in new vehicles at every price point, either as standard or optional equipment, and the data suggests that it's working as intended. A 2016 Insurance Institute for Highway Safety study found that vehicles equipped with forward-collision warning (an audible, visual, and/or vibrating alert given when the system detects a hazard ahead) and AEB were involved in 39 percent fewer rear-end crashes than vehicles without the technologies.

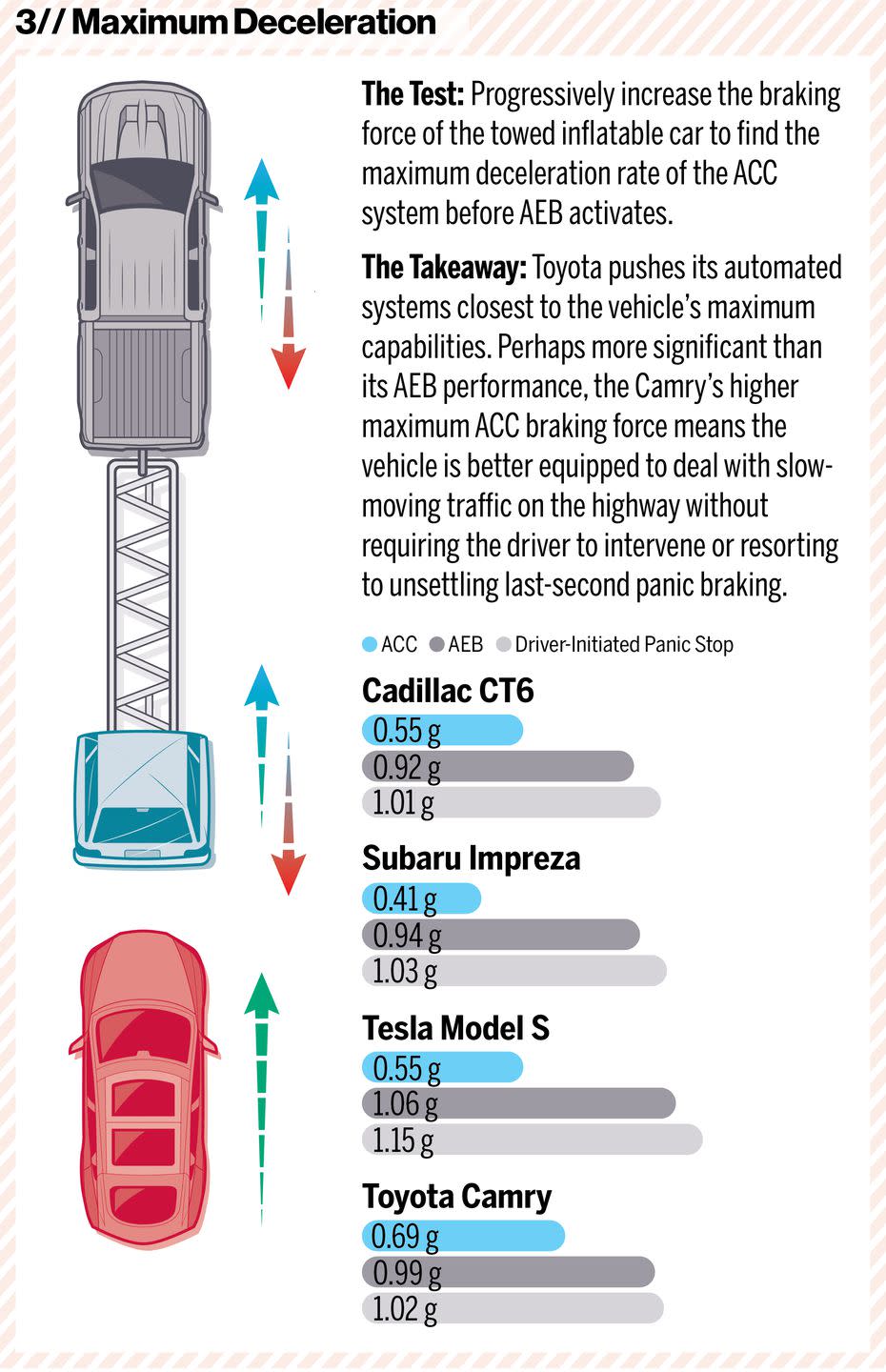

To understand the strengths and weaknesses of these systems and how they differ, we piloted a Cadillac CT6, a Subaru Impreza, a Tesla Model S, and a Toyota Camry through four tests at FT Techno of America's Fowlerville, Michigan, proving ground. The balloon car is built like a bounce house but with the radar reflectivity of a real car, a five-figure price, and a Volkswagen wrapper. For the tests with a moving target, a heavy-duty pickup tows the balloon car on 42-foot rails, which allow it to slide forward after impact.

The car companies don't hide the fact that today's AEB systems have blind spots. It's all there in the owner's manuals, typically covered by both an all-encompassing legal disclaimer and explicit examples of why the systems might fail to intervene. For instance, the Camry's AEB system may not work when you're driving on a hill. It might not spot vehicles with high ground clearance or those with low rear ends. It may not work if a wiper blade blocks the camera. Toyota says the system could also fail if the vehicle is wobbling, whatever that means. It may not function when the sun shines directly on the vehicle ahead or into the camera mounted near the rearview mirror.

There's truth in these legal warnings. AEB isn't intended to address low-visibility conditions or a car that suddenly swerves into your path. These systems do their best work preventing the kind of crashes that are easily avoided by an attentive driver.

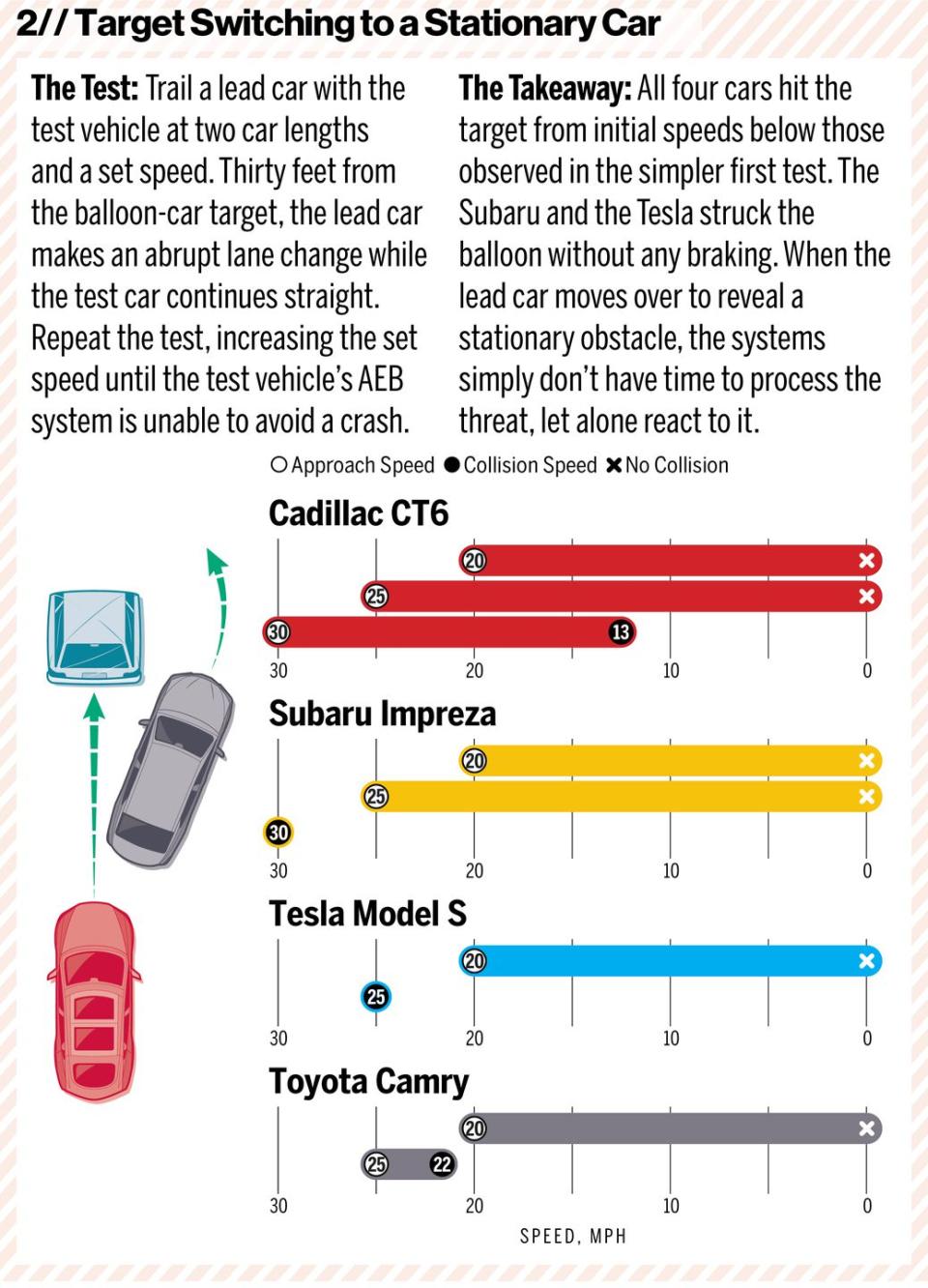

The edge cases cover the gamut from common to complex. Volvo's owner's manuals outline a target-switching problem for adaptive cruise control (ACC), the convenience feature that relies on the same sensors as AEB. In these scenarios, a vehicle just ahead of the Volvo takes an exit or makes a lane change to reveal a stationary vehicle in the Volvo's path. If traveling above 20 mph, the Volvo will not decelerate, according to its maker. We replicated that scenario for AEB testing, with a lead vehicle making a late lane change as it closed in on the parked balloon car. No car in our test could avoid a collision beyond 30 mph, and as we neared that upper limit, the Tesla and the Subaru provided no warning or braking.

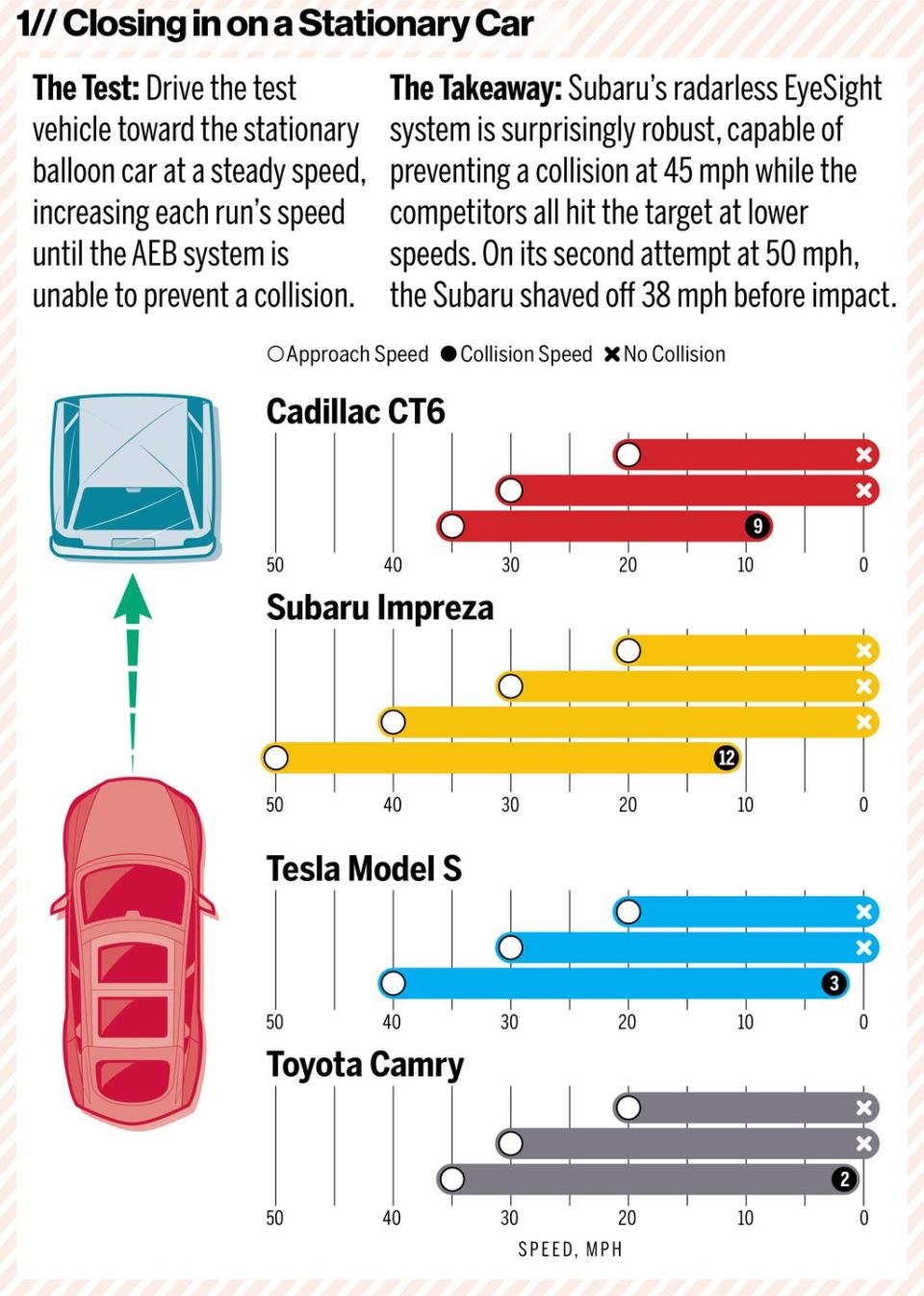

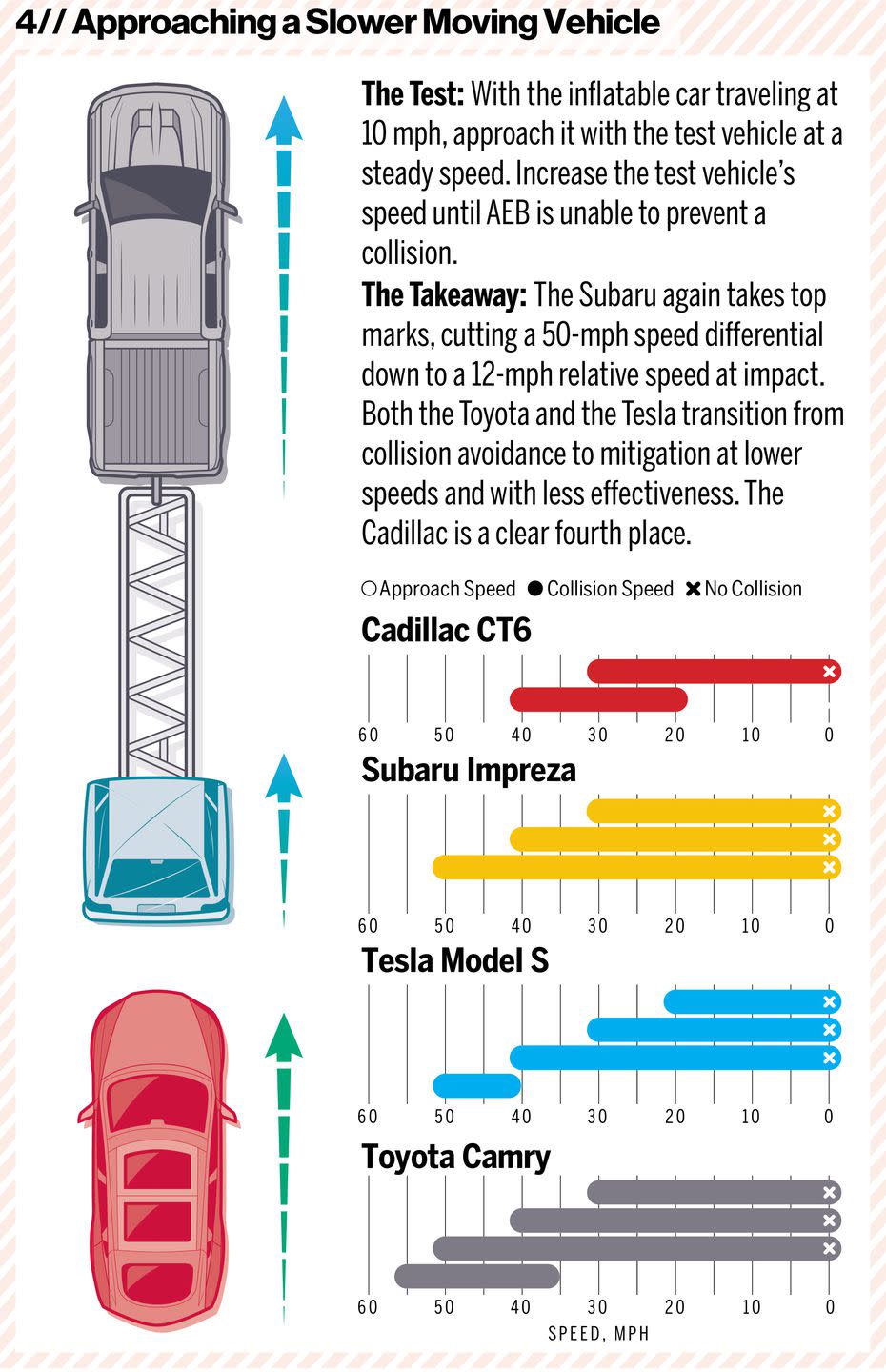

At the moment, automakers have few incentives to push AEB performance beyond the tests already used in regulatory assessment programs and safety ratings. NHTSA's stationary-vehicle AEB test is performed at a single speed, 25 mph, and it only requires that the vehicle scrub off 9.8 mph before impact. In our testing, all the cars easily cleared that low bar, but one model stood far above the rest. The Subaru Impreza-the least expensive car of the four, with a stereo-camera system that eschews the usual radar sensor-still prevented a collision at 45 mph, a higher speed than any other car here, before it nosed into the stationary inflatable target.

The balloon car is firm enough that we only ran our test cases until we found the speed at which an impact was unavoidable. But Thatcham Research, the U.K.'s analogue to America's IIHS, has conducted similar trials at high-enough speeds to know that these systems ultimately reach a threshold where they will neither alert nor brake for a stationary vehicle. Instead, they'll slam into a stopped car at full speed. "As speeds get higher, physically the car can't understand the situation and stop quickly enough. We've seen that with the ACC systems as well," says Matthew Avery, director of insurance research at Thatcham.

Avery explains that manufacturers also face a challenge in deciding whether the system should intervene if there's a possibility that the driver intends to steer around a stopped car or that the vehicle might move out of the way. Along those lines, carmakers are also rightfully self-conscious of how often an AEB system acts on a false positive, with the computer applying the brakes in the absence of a threat. In 2015, NHTSA opened a yearlong investigation into 95,000 Jeep Grand Cherokees following reports that the SUVs were braking for no reason. The probe turned up 176 complaints of inexplicable emergency braking, but the agency found no defects and ultimately decided not to issue a recall. For the moment, these annoyances simply have to be tolerated by automakers and their customers. "From a technological perspective, if you'd like to reduce the rate of false positives, the rate of false negatives [crashes in which AEB does not activate] has to go up, and vice versa," says Raj Rajkumar, co-director of the General Motors-Carnegie Mellon Autonomous Driving Collaborative Research Lab.

Our tests also exposed the infallibility myth that surrounds computers and automated vehicles. Driving the same car toward the same target at the same speed multiple times often produces different results. Sometimes the car executes a perfectly timed last-ditch panic stop. Other times it brakes late, or less forcefully, or even periodically fails to do anything at all. In our stationary-vehicle test, the Impreza's first run at 50 mph resulted in the hardest hit of the day, punting the inflatable target at 30 mph. It was only on the second attempt that the Subaru's EyeSight system impressively trimmed the speed to just 12 mph before the collision. All the results in the charts in this feature show a car's best performance.

Rajkumar says the next-generation AEB technology could improve on two fronts: Artificial intelligence may evolve to better identify collision threats and apply the brakes appropriately, and the addition of more-expensive lidar sensors could bring another level of certainty and precision to detecting obstacles. Collision-avoidance systems are the airbags of the 21st century, reframing automotive safety. But this time, the industry is shifting from technology that protects occupants in a crash to preventing the impact in the first place. Today's systems are impressive and likely to get only better, but know that even a good AEB system is no substitute for a diligent driver.

From the November 2018 issue

('You Might Also Like',)

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos