NC governor orders Confederate monuments removed at Capitol after statues toppled

Gov. Roy Cooper ordered three Confederate monuments removed from the state Capitol grounds to protect public safety, he said in a statement, less than 24 hours after protesters pulled down two bronze soldiers from the 75-foot Confederate monument at the Capitol.

The monuments include memorials that have stood at the State Capitol for more than a century: the remainder of the North Carolina Confederate monument, the monument to the Women of the Confederacy and the Henry Wyatt Monument.

Crews removed the Wyatt Monument and the Women of the Confederacy statues Saturday morning.

Sunday, crews removed the biggest of them all — the Confederate artillery soldier holding a gun that has stood over Hillsborough Street for 125 years.

“I am concerned about the dangerous efforts to pull down and carry off large, heavy statues and the strong potential for violent clashes at the site,” Cooper said in a statement Saturday afternoon. “If the legislature had repealed their 2015 law that puts up legal roadblocks to removal we could have avoided the dangerous incidents of last night.

“Monuments to white supremacy don’t belong in places of allegiance, and it’s past time that these painful memorials be moved in a legal, safe way,” Cooper said.

Friday night, after protesters removed the bronze statues, they hung the statue of a cavalryman by its neck from a streetlight. The other statue, an artilleryman, was dragged through the streets to the Wake County Courthouse, and later was carried away by police in a golf cart.

On Saturday, crews removed the 7-foot-tall monument to the North Carolina Women of the Confederacy, dedicated in 1914, and The Henry Wyatt Monument, dedicated in 1912. The third monument has stood since 1895.

About 60 people crowded around the work crews, chanting “Black power” and singing “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

“Once we get past this, we’ll be a better nation,” said Marvin Taylor of Raleigh, holding his daughter. “We’ll be unified. This is a first step of a work in progress.”

Around 11 a.m., crews separated the statue atop the Confederate Women’s Monument from its concrete base. It took about two minutes to hoist the monument dedicated to women, off its pedestal and load it on a flatbed.

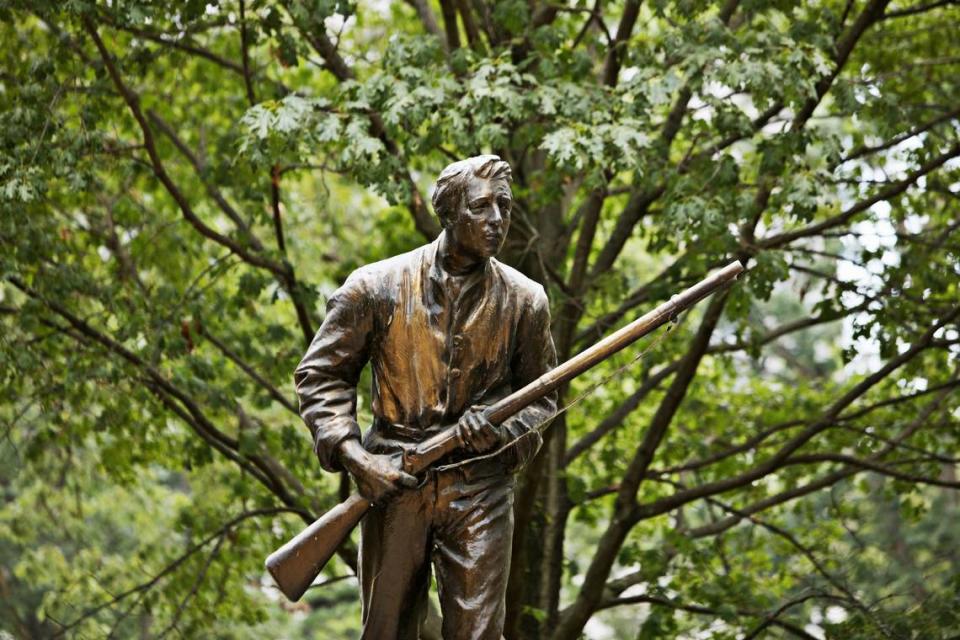

The Henry Wyatt Monument, a bronze statue atop a granite base, depicts the first Confederate solider to die in battle. It was removed shortly after the women’s statue was hauled away.

The Wyatt statue took a bit longer to remove when a corner of metal clung to the concrete, seeming to struggle against removal. But then Wyatt, too, dangled in the air, thick straps under his arms, carted away to cheers.

Some shouted at the statue, “See you never” and “Maybe you’ll get in a museum.”

Who gave the order?

The State Capitol Police, which falls under the N.C. Department of Public Safety, is tasked with keeping the Capitol grounds safe.

State Capitol Police Chief Chip Hawley was overseeing the Capitol Police response to the protesters and consulting with Department of Public Safety Secretary Erik Hooks, said Pamela Walker, a spokesperson for the department, in an email to The News & Observer Saturday afternoon.

Officers stopped an initial attempt to pull down parts of the memorial Friday, and several officers were injured, Walker wrote.

After dark, the crowds grew and the situation escalated again.

“In working to strategically balance the public’s safety and the safety of the officers, the chief determined it was best to not re-engage on the statue and as a result no one was seriously injured,” Walker wrote.

Kerwin Pittman, a Raleigh social justice advocate who has helped lead recent protests, said the monuments taken down Friday should have been removed long ago. But it was satisfying to see them come down on Juneteenth, which celebrates the end of slavery. He wasn’t expecting to see them removed, but also was shocked because of recent events.

“My initial reaction was bittersweet,” Pittman said. “It was sweet to see these relics of oppression come down on the Capitol grounds. It is bitter because it took the citizens, rather than the officials we actually elected, to bring them down.

Saturday, he was at the Capitol grounds to watch the Confederate Women’s Monument be removed.

“The question is, did they take it down because they didn’t want us taking it down?” Pittman asked. “Or because of the racism these Confederate statues represent? There used to be a lot of red tape you had to go through. Now all of a sudden you can just take them down. Shame on you, Raleigh.”

He called the removal of the statues history in the making, but only “a small step in dismantling the optics of what (the statues) stand for.” He wants to see policy change across education, housing, employment and most importantly, criminal justice and law enforcement.

“What you see is an outcry from the people,” he said.

By Saturday afternoon, a crowd of more than 100 people gathered to watch the obelisk come down, sprawling out on the lawn or setting up folding chairs under the trees. Cooper did not say when the monument would be removed.

Nearly all of them wore masks, but strangers shook hands and chatted in small circles, drawn by a common compulsion to witness a long-sought moment.

“I grew up here,” said Marcus Jones, 37, who is Black. “I’ve been down here 1,000 times. I’ve never understood why these are here. I understand caring for your dead. But it’s not right, what they stood for, and making people who look like me look at it. I’m happy. I never thought I’d see this.”

As the wait dragged on, the chats turned to heated arguments as a few spectators waded onto the crowd questioning the legitimacy of Black Lives Matter as a slogan. At 3:30 p.m., Capitol police cleared the square and began fencing it off.

But the obelisk remained standing into the evening as a new group of protesters marched to the monument’s base and chanted “No justice, no peace, defund the police.”

They shouted names of victims of recent Raleigh police shootings — Soheil Mojarrad and Akiel Denkins — along with Kyron Hinton, who was attacked by a Wake County sheriff K-9 dog while standing in the street.

“Hey hey, ho ho, that monument has got to go,” they shouted.

Monument legislation

The Confederate statues have received renewed attention following the police killing of George Floyd in May. Protesters in North Carolina and around the country have called for the end to racism and implementing police reforms. Asking for the removal of Confederate statues has been one of protesters’ calls to action.

But in North Carolina, those who have sought to remove the statues have been bound to a law passed in 2015.

Then-Gov. Pat McCrory signed a new law, backed by the Republican-led General Assembly, that essentially banned the removal of Confederate statues. Lawmakers named it the “Cultural History Artifact Management and Patriotism Act of 2015.”

The News & Observer previously reported that the law was passed as a response to increasing calls to take down Silent Sam, the Confederate statue on UNC-Chapel Hill’s campus that protesters eventually took down themselves in 2018.

The 2015 law passed the N.C. Senate unanimously, the N&O reported. But then a white supremacist named Dylann Roof killed nine Black churchgoers in South Carolina, which led to increased attention on Confederate symbols nationally. When the bill then went to the N.C. House, the N&O reported, it had become a partisan issue. Only two Democrats voted for it — one of whom, Rep. William Brisson, has since changed parties to become a Republican.

Last Monday, the N.C. Senate voted unanimously to spend $4 million on two African-American monuments downtown, one at the state Capitol building and one near the governor’s mansion. The measure is now at the N.C. House awaiting final approval. Cooper and Republican legislative leaders have previously voiced support for the project, the N&O reported

North Carolina native and NAACP board member Rev. William J. Barber II, a co-founder of the National Poor People’s Campaign, said racist statues need come down, but he is focused on the larger issues of policies and laws that need to be changed.

“There certainly is a place for the statues to come down, but we have got to change the statutes,” he told The News & Observer in a phone interview Saturday afternoon.

He said laws have blocked healthcare, living wages and quality education, while mistreating the people who are incarcerated and undocumented.

On Saturday, more than a million people watched on Facebook a virtual March of the Mass Poor People’s Assembly & Moral March on Washington, Barber said. The campaign is focused on fighting systemic racism, poverty and other issues.

The statues should have never gone up he said, but the larger issue is why they did.

“And that is those who have been committed to policy racism,” he said.

One arrest Friday, officer injuries

Walker said at least three Capitol police officers were injured during the protest Friday night.

“One officer has a fractured wrist, another has lacerations to his hand and one had to have his eyes flushed due to having an unknown liquid thrown in eyes,” Walker wrote. “I am told that officers had paint and unknown liquids, possibly urine, thrown on them, as well as rocks and frozen water bottles thrown at them.”

One person was arrested on several charges, including assault on a law enforcement officer, trespassing, unlawfully resist, delay or obstruct a public officer, Walker wrote. Other arrests and charges may be forthcoming, she said.

Saturday morning, Republican Senate leader Phil Berger questioned why law enforcement were managing the crowd for some time but then “abruptly left” the area Friday night. That allowed protesters to go in and tear the statues down with no one to stop them.

“I’m aware of only one person in this state who has final authority over state law enforcement,” Berger continued, referring to Cooper. “Did Gov. Cooper order the police to abandon the Capitol grounds? If not, who is in control of this state?”

Cooper did not respond Saturday to criticism about him.

Republican Lt. Gov. Dan Forest called the removal of the statues Friday night “utter lawlessness” in a press release Saturday morning. He is running against Cooper, a Democrat, for governor this November. He said Cooper deserves blame for the police not stopping the protesters.

“Last night’s destruction occurred on state property, right next to his office,” Forest said. “It is clear that Gov. Cooper is either incapable of upholding law and order, or worse, encouraging this behavior.”

North Carolina House Speaker Tim Moore said Cooper’s administration told law enforcement to stand down “to justify removing the statues unilaterally instead of following the process laid out in state law.”

McCrory, the Republican defeated by Cooper in 2016, tweeted Friday night that it was “disgusting to watch” the protesters tearing down the statues.

No curfew planned

Raleigh Mayor Mary-Ann Baldwin said Saturday in an interview with the N&O that she believes “these statues should come down.”

“I think what is happening today is the right thing for us to do and the governor to do for history and public safety,” she said. “But if we ever needed any evidence that this was a public safety issue, last night was it. That was my biggest concern. That somebody was going to be hurt.”

There are no Confederate monuments on city-owned property, but a statue of Josephus Daniels, former publisher of The News & Observer and lifelong white supremacist, was removed from Nash Square earlier this week. Nash Square is owned by the state but is maintained by the city of Raleigh, Baldwin said. The Daniels family owns the statue and had it removed.

The city is not considering issuing another curfew, she said. A curfew was issued for about a week after protests following Floyd’s death turned destructive in Raleigh. The first two nights of protests — May 30 and 31 — began peaceful but became destructive after law enforcement fired tear gas, foam bullets and pepper spray and looters ransacked downtown businesses. Nightly peaceful protests in Raleigh have continued with few arrests.

“Everything is still so raw, angry and wounded that it is still hard to get beyond that,” Baldwin said. “After what happened, with the murder of George Floyd, the anger and outrage from that is still very strong. It’s raw. And then the rioting and looting that happened. That is raw. It makes people feel vulnerable and afraid. So it’s everything that has transpired the last three weeks that is contributing to this feeling of vulnerability.”

Council member Saige Martin shared a photo of one of the Confederate statues hanging from a lamppost and saying he is proud of his city.

“Overdue,” he said. “A reminder that y’all will not sit around and wait. Proud of my city, always. Especially tonight.”

In a Facebook group focused on local politics, Raleigh Council member David Cox wrote he agrees with the removal of the statues and the “time is long overdue for change.” But he supported removing the statues through a “democratic process.”

“We must be consistent and recognize that someone acting randomly for good can easily be another person acting randomly for harm,” Cox said. “Random people taking justice into their own hands is not sustainable. We must work through our democratic process. To do otherwise risks the very freedom and liberty that we all want and love.”

Women of the Confederacy

The bronze Women of the Confederacy memorial includes a scene of a seated older woman, holding a book, and a boy holding a sword.

It faces Morgan Street and has two stone benches facing each other, flanking the monument. It was donated by Ashley Horne, a Confederate veteran and one-term state senator.

It was dedicated June 10, 1914, and was intended to honor the the hardships and sacrifices of North Carolina women during the Civil War, according to Documenting the American South.

“The woman, representing the women in the South as the custodians of history, imparts the history of the Civil War to the boy,” the description says. “The two relief plaques portray the Civil War; the eastern side shows soldiers departing for war and leaving their loved ones behind, while the western side depicts a weary or injured Confederate soldier returning home.”

Wyatt statue

Wyatt is depicted holding a gun across his body walking into battle, according to Documenting the American South, an initiative by the UNC-Chapel Hill library.

Wyatt, an Edgecombe County native, was killed at the the battle of Battle of Bethel Church in Virginia on June 10, 1861, according to the N.C. Department of Cultural Resources, which keeps a list of state Civil War monuments. The statue was dedicated on June 10, 1912.

Research shows that across the country, most Confederate statues were put up not in the years immediately after the Civil War, but in the early 1900s, coinciding with the passage of Jim Crow laws that started in the late 1890s and continued into the 20th century.

Ashad Hajela contributed to this story.