‘It’s a crime.’ Mogul aims to demolish famed architect’s Coral Gables masterpiece home

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

One of the most celebrated modern houses ever built in Miami-Dade County, famed architect Alfred Browning Parker’s waterfront “Sea Aerie” home in Coral Gables, appears headed for eradication by a Texas construction mogul who paid $36 million for the masterpiece in August to tear it down.

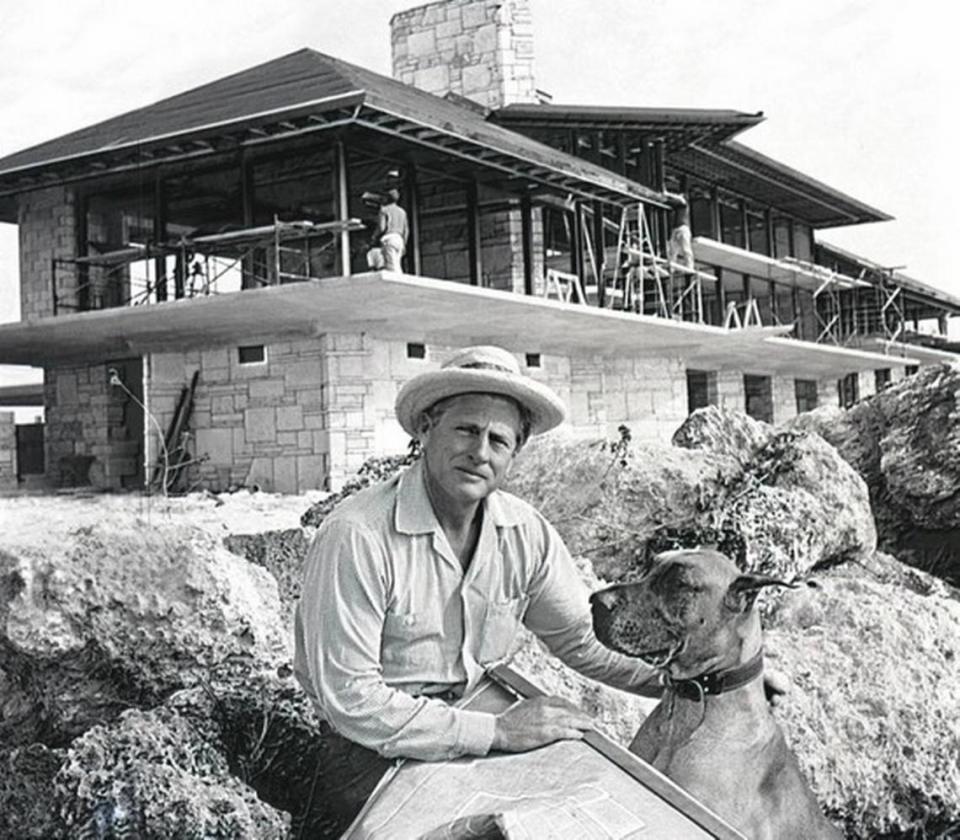

The richly appointed house, which commands majestic views of Biscayne Bay and the open Atlantic Ocean, has long been considered one of Parker’s most important and advanced designs. Parker, widely regarded as Florida’s preeminent Modernist architect and, in the words of the author of a book on his work, a “creative genius,” designed and built the 11,000-square-foot home for his family in 1963 in the city’s then-new Gables Estates section.

Architects and critics say the house, featured in numerous articles and books, stands as a well-preserved exemplar of Parker’s “organic,” environmentally-oriented approach to architecture. And it represents an unusually innovative response to South Florida’s subtropical climate and the need for buildings to absorb the wind and surging waters of hurricanes.

But Gables Estates, which consists of a series of low-lying artificial islands where all homes are waterfront and resale prices reach into the tens of millions, has become a focal point for teardowns as older mansions are replaced by ever more grandiose palaces. The family trust of longtime owner Mary Jean “Bunny” Bastian, a prominent Gables socialite and philanthropist, had put the house up for sale after her death last year, initially asking $45 million, before the Texas businessman eventually bought it for $9 million less.

As the application for total demolition of the Parker home at 140 Arvida Parkway now wends its way through the Gables’ building bureaucracy, shocked members of the Parker family, preservationists, city officials and architects across the country say they’re disconcerted that anyone would pay such a high price for an architectural landmark of its stature only to destroy it.

Though most of Parker’s designs were built in South Florida, his fame was international. His architecture broke with conventions and sought to provide the occupants of his homes and buildings a feeling of spaciousness, geometric variety and a close connection to the outdoors, with an appreciation for the environment of South Florida that has largely since been lost in the building field, architects familiar with his work say.

“I think it’s dreadful, unbelievable,” said the late Parker’s son, Coconut Grove architect Robin Parker, who worked as a dollar-an-hour laborer on the home’s construction while in high school. “This is a fantastic house. I can’t imagine anyone even contemplating tearing it down. It’s a crime.”

Stymied by Florida law

Yet the city — a well-known bastion of historic and architectural preservation that won a court battle a decade ago to save another Parker-designed home — finds itself powerless to block the impending disappearance of “Sea Aerie.”

If it falls, as seems probable, the house would be a victim of one of several developer-friendly preemption laws passed by the Florida Legislature to restrict local officials’ once-routine zoning powers.

The pertinent one in this case, effective July 1, 2022, bars cities and counties from designating homes as protected landmarks if they sit at or below the high-water line in designated flood zones, as the Parker house does. That means the Gables is obligated to issue the demolition permit without a historic-preservation review, typically a routine matter under city regulations.

The same state law paved the way for the demolition in August of mobster Al Capone’s manse on Miami Beach’s Palm Island, after a prolonged battle by preservationists to save it.

The law was passed ostensibly to allow homeowners to replace houses threatened by increased flood and storm-surge risk driven by rising seas and climate change, but that was already allowed by local authorities in most places and circumstances. Critics call the legislation a gift to developers, real estate speculators and ultrawealthy buyers increasingly looking to build mega-mansions on valuable coastal properties without hindrance.

Coral Gables commissioners decried the law in a resolution approved in August 2022, predicting it would lead to the destruction of historic properties, an “irreversible action which contributes to the loss of the city’s identity and sense of place.” The resolution urged the legislature to rescind the measure in this year’s session, but that did not happen.

Coral Gables Vice Mayor Rhonda Anderson said the law’s chickens are now coming home to roost, as predicted, and she fears the Parker house will be far from the last significant home in the city to fall.

The commission’s resolution noted that the coastal city, which is home to some 1,200 historic landmark properties, may in addition “have a significant number of undesignated properties that are potentially eligible for historic designation.” Buildings typically become eligible for consideration once they reach 50 years of age.

Anderson complained the law encroaches on city zoning powers and applies in blanket fashion, providing no flexibility or criteria to determine how vulnerable a historic home really would be to storm surge or flooding.

The three-story Parker home, for instance, features numerous forward-looking, climate-resistant features, including having most living areas on the second and third floors and what the architect called a Seaway, a wide breezeway on the ground floor designed to channel storm surge through the house to an open courtyard behind it. Support columns are angled to disperse the force of surging water. The swimming pool occupies an elevated platform.

But the state law doesn’t allow for consideration of such flood-mitigation design features, now common elements in new homes built in flood zones.

“I’m very frustrated,” Anderson said in an interview. “It is having consequences. What can the commission do? If we don’t have the power, we can’t do it. It’s pretty disturbing when you talk about significant architecture in our communities. We lose our history, and it’s sad.”

Meanwhile, the director of Docomomo U.S., a national group that advocates for the preservation of modern architecture, said the Florida law sets a “dangerous” precedent and called the impending loss of the Parker home “disturbing.” Demolishing homes and buildings, especially those made with quality materials, is wasteful and far from environmentally friendly, Liz Waytkus said.

“People should be aware of what’s happening. It’s a misinformed way of dealing with the climate crisis,” said Waytkus, whose organization will hold its national meeting in Miami next June. “Preserving historic places is critical in that we are retaining buildings and materials, and not adding resources to a landfill.”

New owner has nothing to say

Alex Almazan, a Miami attorney acting as trustee for the Parker home’s new owner, listed in public records as the 140 Arvida Parkway Trust, declined to comment. The buyer’s identity is shielded by the private trust.

But a source familiar with the house sale identified the buyer as Felix Sorkin, founder and president of General Technologies, a national firm based outside Houston that designs and makes products for reinforced concrete construction. Sorkin, who holds numerous patents, already owns a waterfront mansion in Coral Gables, in the Sunrise Harbour section, a short distance north of the Parker home. A limited liability corporation he controls paid $10.6 million million for the Sunrise Harbour home in 2021, the Miami-Dade property appraiser’s website shows.

Regarding Sorkin’s Arvida Parkway house, a pair of determination letters issued by Gables officials this year and in 2022 conclude the state preemption law ties the city’s hands because the former Parker property sits in a federally designated flood zone, at or below the base flood elevation. That’s the height of expected water levels in a storm at a particular location.

That the city would otherwise seek to declare the Parker house a protected historic landmark seems likely.

Three other Parker-designed homes already are designated Coral Gables landmarks, including 2 Casuarina Concourse, also in Gables Estates. Coral Gables officials beat a $7 million lawsuit filed in 2013 by owners of the house when a court, echoing numerous previous judicial rulings, ruled the city has the legal authority to block demolition of a historically significant property. George Washington Carver Middle School, which Parker designed, is also on the list of Gables historic landmarks.

Under Coral Gables ordinances, ordinarily all demolition applications are reviewed by the preservation office for historic or architectural significance. Those deemed eligible are referred to the city’s historic preservation board for possible designation.

Later this month, in fact, the board will consider yet another Parker-designed home for historic designation, this one in the Hammock Lakes section.

After a local developer sent the city a letter asking if the 1964 home, at 5005 Hammock Park Drive, is historically important, the city’s preservation office concluded it meets three of the criteria for designation for architectural significance. Meeting only one criterion is legally sufficient for designation, which bars demolition. The property, which according to online county records remains in the hands of longtime owners, does not appear to be listed for sale. A city spokesman said a full analysis by the preservation office is not yet ready. The board will hear the case on Oct. 18.

Unlike the Parker-designed Arvida Parkway home, which is open on all sides and features generous use of lavish materials typical of the architect’s grander designs — Honduran mahogany, oolitic limestone, terracotta, glass and steel — the Hammock Lakes house represents a different approach the architect often took on smaller lots in heavily wooded areas like Coconut Grove.

The Hammock Lakes house sits in a thick forest of trees and, reflecting its surroundings, is almost entirely made of wood, save for garden walls, a base and a large chimney sheathed in keystone, photos on file with the city show.

‘One of the best recognized modern architects’

The prolific Parker, who apparently designed more than 500 homes, churches and commercial buildings during a 60-year career launched in Miami in 1946, was in his heyday Miami’s equivalent of Frank Lloyd Wright. The most famous American modern architect inspired Parker’s designs and approach, which was finely attuned to the site of a home or building, and lavished rare praise on his Floridian counterpart.

“Parker was one of the best recognized modern architects in Miami and the U.S.,” said Allan Shulman, a Miami architect and University of Miami professor who helped organize a 2016 HistoryMiami museum exhibit on Parker’s work. “He was a believer that the house should be natural, that it should embody natural materials and natural principles of ventilation and co-existence with its surroundings.”

The Arvida Parkway house headed toward demolition, Shulman noted, was one of several “extraordinary” houses that Parker designed and built for his own and his family’s use, and is in some ways the most ambitious. Its elegant resiliency features, devised by Parker well before the concept became commonplace, are instructive even today, he said, “offering many lessons to us architects and builders working now.”

“I would say the house is one of his masterpieces,” Shulman said. “I think the house should stay.”

Yesterday’s marvelous homes, today’s teardowns

But in ever-changing, boom-and-bust Miami, yesterday’s architectural masterpieces are too often today’s teardowns, said Randolph Henning, an architect who helped organize the HistoryMiami exhibit and wrote “The Architecture of Alfred Browning Parker, Miami’s Maverick Modernist,” published by The University Press of Florida.

Many of Parker’s homes and buildings, including some of his best, have been lost to demolition and his name, once ubiquitous, has faded in the city he long called home, Henning said.

“He was a rock star when he was alive,” Henning, a Pompano Beach native who lives and works in North Carolina, said in an interview, alluding to the expected teardown of the Arvida Parkway house. “Money talks down there. It’s just a different attitude down there. It’s distressing.

“Parker was the best architect who ever practiced in Florida and this is one of his best houses. There is no reason for it to be demolished other than taste. But you can’t explain stupid. It’s like buying the Mona Lisa and throwing away the painting because you want the frame. It’s very arrogant and very selfish.”

On Arvida Parkway, the architect aimed squarely at grandeur.

Parker, looking to build a new home for his wife and five children, scouted the area by helicopter in the early 1960s for a suitable site. To promote his new development, Gables Estates developer Arthur Vining Davis promised Parker a discount on a lot if he finished a new house within a year. The architect did so.

Parker was at that point already a sought-after architect, a leader in an informal group of Coconut Grove architects who sought to work with the local climate and work with natural materials at a time when the growing prevalence of air-conditioning was changing how homes and buildings were designed and built. No two Parker designs were the same, because he tailored each project to its surroundings. Some of his homes and buildings were rectilinear, some were round and others shaped like triangles.

An environmental approach to design

Parker sought to maximize his environmental approach at Gables Estates.

“Dad worked with everything. He worked with the site, he worked with the breezes, he worked with the angle of the sun,” son Robin Parker said in an interview.

The elder Parker acted as general contractor and lived on the Gables Estates site in a trailer and later in the garage maid’s quarters during construction, overseeing every detail, his son recalled. The terracotta roof tiles, for instance, were custom-made by the famed Ludowici factory in Ohio in a green tint the elder Parker picked from ooze in the bay, his son said.

He designed the house, oriented to the southeast because of the site’s location, to maximize panoramic views and take advantage of prevailing breezes for natural cooling, while shading its terraces and windows from the sun’s heat and glare. They are principles South Florida architects have moved away from in favor of sealed air-conditioned spaces, although the approach has seen something of a recent revival.

The side of the house facing the water boasts floor-to-ceiling “persiana” doors of bug-resistant Honduran mahogany, a favorite Parker material, that allows the interior to be fully open to the environment. A frame of steel beams and reinforced concrete columns provide strength in the face of wind and surging seas. So do angular planting boxes, terraces and support columns designed to disperse the impact of wind and water.

A prow-like glass enclosure on the soaring interior stairway made for heady views that created an experience of high altitude — thus the house’s “Sea Aerie” nickname. That was only one of numerous perceptual tricks Parker used in his design, some gleaned by his study of Venice’s Piazza San Marco, to amplify the feeling of spaciousness inside and out.

The main house is connected to a separate garage and service wing by an elevated pool, wider at one end to give the impression of distance. The courtyard isn’t entirely square, but slightly irregular at the corners to make it seem larger than it is to an arriving visitor.

The Seaway, the columned opening at the base of the house designed to channel floodwater, actually worked, Robin Parker said, recalling the time he bodysurfed through the house during a storm.

Art was integrated into the house design, including an antique Japanese screen later valued at millions of dollars, and concrete sculptures on exterior support columns by artist Albert Vrana, a Parker friend, of crabs and other sea creatures found in nearby waters.

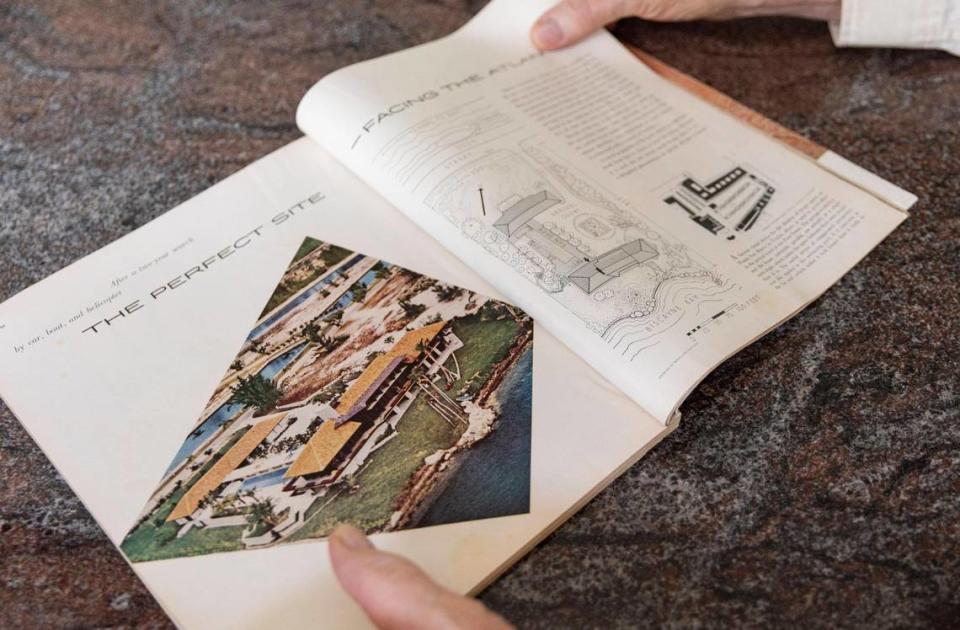

Featured in House Beautiful in 1965

So spectacular and innovative were the results that House Beautiful dedicated its entire May 1965 issue to the house, naming it its Pace Setter Home of the year — a significant honor at the time that Parker had received twice before. The extensive, dramatic house pictures in the issue were by renowned architectural photographer Ezra Stoller.

“Seascape, landscape, sunscape, cloudscape — from every corner ... a different vista delights the eye,” the magazine noted.

Its editor added: “It is a home that makes a heroic statement in its inner vistas and serenities, its lofty prisms of glass and stone. A true Pace Setter in concept and innovations.”

Parker’s work is receiving renewed national attention. PBS will broadcast a new documentary, “Perfect House, Magic City: the World of Alfred Browning Parker,” which features the Gables Estates house among other designs, starting in December.

The seven-bedroom, five-bath home proved too much for Parker’s changing family needs, as his five children went off to college or left the nest as adults. After barely three years, he sold it in May 1966 for $675,000 to entrepreneur James Ryder, who started Ryder System Inc. and made a fortune leasing trucks before passing away in 1997.

In 1984, Bunny Bastian and her husband, James Bastian, bought the vast Parker-designed home for $1.2 million. James Bastian, who died in 2000, was a controversial figure — a former Central Intelligence Agency attorney who owned the notorious Southern Air Transport, a cargo airline long associated with the spy agency and unsavory doings. Under Bastian’s ownership, Southern Air played a central role in the Iran-Contra weapons scandal under the Reagan administration in the mid-1980s.

Henning said Bunny Bastian was well aware of the home’s architectural distinction, calling on Parker to consult on renovation work before his 2011 death, and at times hosting visitors from around the world wanting to tour it.

Parker-designed buildings preserved

It’s unclear how many Parker buildings are protected as historic landmarks. The city of Miami in recent years preserved one home, now owned by Carrollton School of the Sacred Heart in Coconut Grove, but allowed two others nearby to be demolished — including a house Parker designed for his mother, Jewel Parker. That 1957 house, which backed up to the home Carrollton now owns, was set in a wooded grove and called Jewel-in-the-Treetop, but a subsequent owner allowed it to fall into ruin.

Others, though not protected, are nonetheless cherished by owners and command high prices. Parker’s longtime studio, built alongside the first home he designed for himself in 1943, still stands in the Grove and remains in use. A 1959 Parker-designed house in unincorporated High Pines, abutting Coral Gables, sold for nearly $4.3 million in 2021.

The iconic home Parker designed in Coconut Grove for himself after the Gables Estates house, Woodsong, is clad entirely in mahogany and consists of separate pods connected by an elevated a swimming pool that runs through the compact compound like a stream. It was purchased earlier this year for $4.2 million by Los Angeles developer Pamela Day. She told an interviewer she considers herself a custodian of the 1968 house, named to Wallpaper magazine’s “ten best residential builds” in the world in a 2006 issue.

Familiar Miami churches and commercial buildings designed by Parker include the flying-saucer-like St. Louis Catholic Church in the village of Pinecrest and the octagonal restaurant at Bayside Marketplace in downtown Miami that’s today occupied by the Hard Rock Cafe, though it’s been significantly altered.

Still hope for reconsideration

Some preservationists still hope that the Texas buyer of Parker’s former Gables Estates home will reconsider and recognize its cultural and architecture value and significance.

“People come here from all over the world and there is no appreciation because there is no foundation of knowledge,” said Karelia Martinez Carbonell, president of the Historic Preservation Association of Coral Gables. “We thought that maybe because of the legacy of the architect and the pedigree of the home, someone would buy it and keep it.

“Yes, they have the right to tear it down. But they also have the right to appreciate the fact that they have a masterpiece on their hands,” she said.