For criminal justice reform to work, Biden must dismantle damage done by 1994 crime bill

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I am an adjunct lecturer in New York University's school of social work. I have seen what happens to young Black and brown men trapped in the injustice of our criminal system. I've also lived it, spending 19 years cycling in and out of prison before earning degrees in social work and turning my life around.

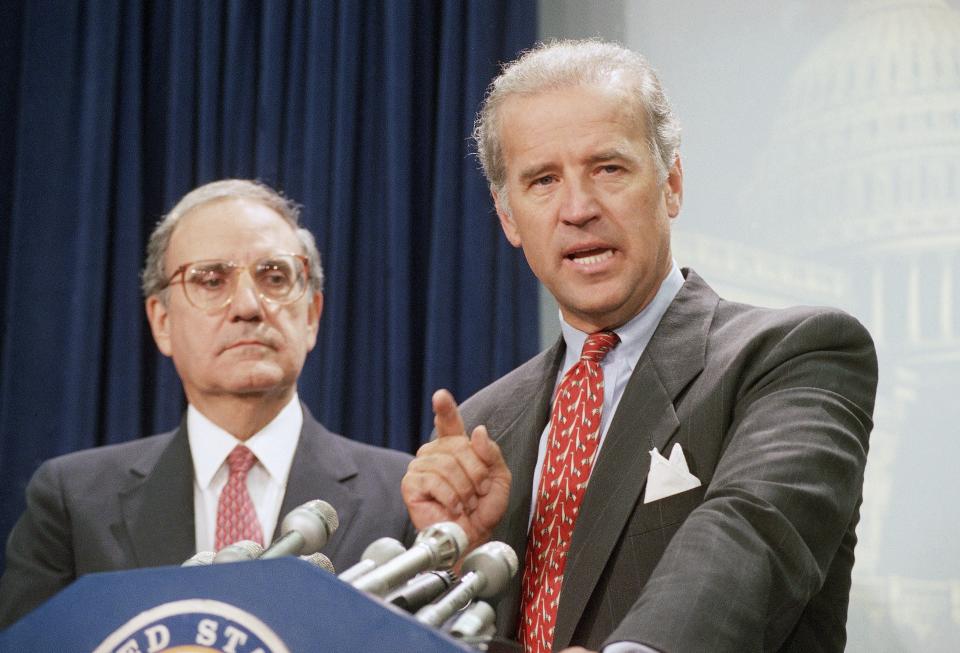

So I've been watching closely as President Joe Biden has shaped the beginning of his presidency as one that champions equity and racial and social justice reform. But he has yet to fully address how he will fix the damage caused by his 1994 crime bill – the act is, in part, responsible for the severe overincarceration of young Black and brown men who disproportionately populate the country's juvenile and adult prisons.

He was the head of the Senate Judiciary Committee, and created and pushed the legislation through Congress that prompted men like me to be called "predators."

Dismantle biases

It's impossible to bring equity to criminal justice without fully dismantling the biases in the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. Biden should use executive orders to eliminate the most damaging aspects that the 2018 First Step Act hasn't already addressed. One example: He could adjust the 85% rule found in the crime bill. That regulation rewards states that force offenders to serve 85% of their time before they are eligible for parole.

Since Biden's famous speech on the Senate floor in 1993 advocating for the crime bill and its passage, much has changed for the worse. Scholarly articles, criminal justice movements and documentaries such as Ava Duvernay's "13th," as well as famed activist and author Michelle Alexander's bestselling book "The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness" all highlight the adverse impact and racist undertone of this legislation.

T-Pain: A year after Floyd's death, nation must do more for Black and brown victims of crime

In November 2008, the night former President Barack Obama was elected, I was sitting in a state correctional institution when the wheels of change began happening in my life. His election inspired in me a sense of hope, as it did for so many Americans. I learned that not only could America change, but I could, too.

Before then, I had spent 15 years absorbing the "superpredator" messaging that started in the 1990s.

Those most impacted by the crime bill were people from poor Black and brown communities who, after serving their time, were released to the same impoverished neighborhoods with no access to employment or educational opportunities and no access to government assistance programs.

Severely stigmatized by society, this was only part of the collateral damage that would ensue for Black and brown inmates. For so many, the cycle of incarceration continues. Each year since that legislation, more young Black and brown folks have found themselves trapped in a caste system, with no remedy or relief.

Biden was right in 1993 when he shared on the Senate floor that society had failed these communities. But he was wrong in his assessment of how America should address the issues: "Cordon them off from the rest of society."

Column: Release people incarcerated under draconian marijuana laws

He was wrong to tell the American people that it didn't matter how Black and brown people got stuck at the bottom. It was wrong to demonize entire groups of people as a "cadre of young people ... born out of wedlock," deprived, without parents, having no socialization skills or conscience. He made them scapegoats for political gain.

A rippling effect over decades

This is not an attack on the Biden administration. In spite of Biden's crime bill mistake, I voted for him and Vice President Kamala Harris.

I watched with intent every comment and speech that he, as well as other candidates, made while on the campaign trail on the issue of justice reform in America. I also watched every debate.

Even former President Donald Trump highlighted the disproportionate criminal justice impact this legislation inflicted on Black and brown communities. Trump also signed the First Step Act – the first major attempt since the Obama administration’s Fair Sentencing Act to undo some of the damage caused by the 1994 crime bill.

REPAIRING AMERICA: Exploring fight for reparations, racial justice across the country

It is my hope that this column will put a human face, a lived experience and a voice of reason on that disproportionate impact. It has had a rippling societal impact far beyond the lengthy prison sentences this legislation called for. There was a time when the most difficult question for me to answer when seeking employment was, "Do you have a high school diploma?" After 1993, the most difficult question became, "Have you ever been incarcerated?"

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

The crime bill brought more emphasis to that last question, and in my experience and that of others, employers started pressing more for information. They were afraid to hire us. We were considered liabilities. Without access to employment opportunities, some attempted to access government benefit programs, only to learn that because of provisions in the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (signed by President Bill Clinton two years after the crime bill), convicted felons who had served time for drug offenses were restricted from participating in government programs.

Although the crime bill called for more than $380 million in drug treatment programs, the funding was limited to certain prisons, in certain states. And the programs themselves were ineffective, providing no continued services or resources to returning citizens upon release. Addiction is not a one-shot or a three-strike deal but a lifetime process; low-level offenders who were no more than recovering addicts were given life sentences.

POLICING THE USA: A look at race, justice, media

I commend this administration for moving forward to end contracts with private prisons and for submitting a request to the Supreme Court to give low-level crack offenders the same opportunity for sentence reductions given for other low-level offenses under the First Step Act. I also commend Biden's admission that the 1994 crime bill was a mistake.

But the damage has been done.

In 1993, Biden stated that there was a consensus that the crime bill was the best way to solve this "cadre of young people" problem. Nearly three decades later, we know that the consensus was wrong.

Today, the bill is seen as an utter failure – one that has created more damage to Black and brown communities than nearly any other legislation in American history. It has propped up mass incarceration and is discriminatory.

President Biden, exercise executive power. Hear the pleas, cries and pains of Black and brown communities across the country who stand with and by you.

Terrance Coffie is an adjunct professor at New York University, a contributing author to "Race, Education, and Reintegrating Formerly Incarcerated Citizens," and the founder of Educate Don’t Incarcerate.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Biden must dismantle damage done by the 1994 crime bill he supported