Critics say KY House bill ‘criminalizes poverty’ with penalties for homelessness

Gregory Searight has “lived rough” outside in Lexington for years, including a stint under a Loudon Avenue bridge. His only contact with police officers came when they sometimes checked on him in the morning and brought him coffee and donuts.

“We was grateful for that,” Searight, 63, recalled in a recent interview. “They ain’t never run us off ‘cause we ain’t never made no trouble. As long as you don’t cause problems, you won’t have problems.”

However, a sweeping anti-crime proposal in the General Assembly — House Bill 5, designated the Safer Kentucky Act — could change things by taking aim at Kentucky’s homeless, among many other targets.

Sign up for our Bluegrass Politics Newsletter

A must-read newsletter for political junkies across the Bluegrass State with reporting and analysis from the Lexington Herald-Leader. Never miss a story! Sign up for our Bluegrass Politics newsletter to connect with our reporting team and get behind-the-scenes insights, plus previews of the biggest stories.

The bill would establish a new crime, “unlawful camping.”

Police would have to charge people trying to sleep or camp in specified public and private spaces that are not designated for camping, including on sidewalks or roadsides, under bridges, or in parks, parking lots, garages or doorways.

Sleeping in a vehicle could count as camping, as could sleeping in tents, huts or other “temporary shelters.”

Local governments could not opt out of enforcing the public camping ban, at risk of being sued by the state’s attorney general. A first offense for unlawful camping would be a violation, punishable by a $250 fine. Repeat offenses would be a Class B misdemeanor, which can bring up to 90 days in jail on top of a $250 fine.

Public camping bans have been controversial in other places. On Friday, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear a challenge to an Oregon city’s ban, to decide whether it violates the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment when there are no available shelter beds for homeless people.

In Kentucky, House Bill 5 also would make it easier to involuntarily commit someone to a mental health facility even without a demonstrated history of criminal behavior that has endangered or harmed others.

It would authorize local governments to designate a zone where homeless people can stay, as long as running water and toilets are provided and the zone is remote enough from population centers to be “separate from any area frequently used for public purposes.”

It would prohibit spending state or federal money on “Housing First” programs that have become popular over the past 30 years. Housing First prioritizes finding permanent housing for homeless people and then, once there is a roof over their heads, providing any mental health or addiction treatment they might need.

Finally, the bill expands the state’s “stand-your-ground” law to allow property owners and tenants to use physical force against homeless people who refuse to leave private property and who use force or threaten to use force.

The bill’s sponsors say it’s intended to prod homeless Kentuckians toward social services and housing assistance.

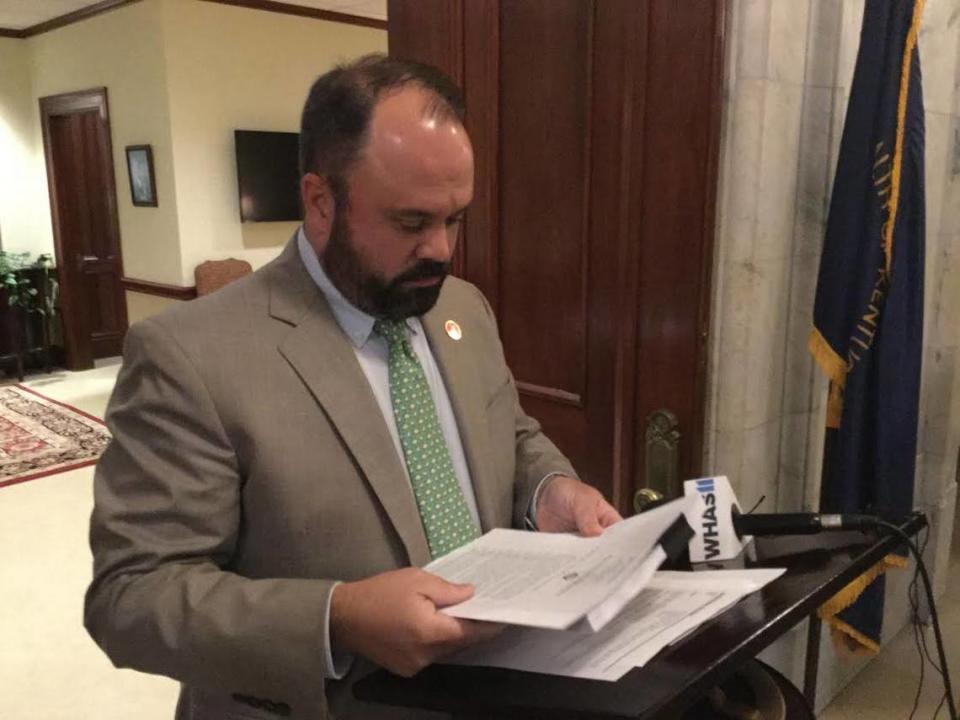

“There’s nothing compassionate about leaving someone on the street with untreated mental illness or drug addiction,” state Rep. John Hodgson, a Republican from Fisherville in Jefferson County, said at a recent news conference in Frankfort.

“Studies show they will spiral down to premature death,” Hodgson said.

“Along the way, they’re going to create other problems. They’re going to devalue the business community. Surveys show the people don’t like to go where unsheltered homeless people are panhandling them on the street or camping on the sidewalk.”

Hodgson warned of a homeless man who raped a woman in broad daylight in downtown Louisville last August.

“We certainly don’t want to suggest that an entire population is like that, but among the unsheltered homeless population is a high-risk element for panhandling, petty crime and things that generally endanger the public,” he said. “And the public health, with things like feces on the sidewalk and drug paraphernalia.”

‘Criminalizing poverty, homelessness’

The House bill has shocked some of the estimated 2,400 homeless people in Lexington and their advocates.

They say it’s cruel to criminalize sleeping outdoors when there sometimes aren’t enough shelter beds in the city (there are about 500 beds year-round, 700 in winter), and the cost of housing is soaring. Rent growth in Lexington last year was among the highest for any U.S. city, with a median apartment price of $1,232 a month.

Activists lobbied the General Assembly this month for $200 million to build or rehabilitate sorely needed affordable housing in Lexington, Louisville and the state’s rural communities.

House Bill 5 would punish people for not having a place to live without actually providing anyone with a home, advocates say. Individuals with no money could be jailed for failure to pay fines, and once they are tarnished with criminal records, they would find it even harder to be hired for a job or approved for an apartment.

“Our No. 1 concern is the message it sends,” said Ginny Ramsey, director of the Catholic Action Center, a privately run shelter on Industry Road in Lexington.

“Instead of our legislators standing up and being a light and saying, ‘We have got to take care of our people in the commonwealth of Kentucky, we have got to be sure they have what they need,’ in their frustration, they’re criminalizing poverty and homelessness,” Ramsey said. “And that’s not Kentucky.”

Ramsey worries that political rhetoric demonizing homeless people could inspire harassment, and even violence. People living on Lexington’s streets have been jeered, pelted with objects and even beaten over the years by those who saw them as less than human, she said.

“That is what these type of words create. They give people license to think, ‘Well, they’re the other.’ But they’re not the other. They are your mother, your father, your brother, your sister. I mean, they are human beings,” she said.

Searight said it’s easy for state lawmakers to push homeless people around because they live safe, comfortable lives and mistakenly believe they could never be in the same position.

“I had a house. I had the picket fence. But life shows up,” Searight said.

“What they need to do is take some of them politicians and put them out here for a whole week,” he said.

“Take their credit cards. Give them a backpack. Let them see how it feels to be out here in the cold, under a tree, out in the elements. It’s not fun. They wouldn’t even survive out here because they wouldn’t know what to do.”

Promoted by a Texas think tank

The homeless language in House Bill 5 is based on model legislation crafted by the Cicero Institute, a “free society” think tank in Austin, Texas, that was founded by and based on the philosophy of its board chairman, tech billionaire Joe Lonsdale.

The Cicero Institute spent nearly $10 million promoting its views in 2022, according to its most recently available tax returns.

Since 2021, legislation including at least some of the think tank’s ideas on homelessness, has passed in Texas, Missouri, Tennessee, Utah and Georgia.

“To date, we’ve achieved legislative victories in five states on this issue of homelessness, with full overhauls in two states and many more in the pipeline,” Lonsdale wrote in an essay in the New York Post in December.

“We’ve banned dangerous tent encampments in multiple states and cities,” he wrote. “We’ve made it easier to civilly commit those who are mentally ill and need treatment. And we’ve pulled money from failed Housing First programs.”

The Cicero Institute has Kentucky connections. It hired Bryan Sunderland, who was deputy chief of staff to former Republican Gov. Matt Bevin, as director of advocacy to lead policy outreach across the states. Bevin’s chief of staff, Blake Brickman, is an adviser to the think tank and works for one of Lonsdale’s companies.

In a phone interview, Sunderland said the Cicero Institute’s approach, when adopted, has started to clear away the homeless encampment “tent cities” ailing so many American downtowns.

“Where I think most people come down on this is that it’s not compassionate to leave someone on the streets. It’s inhumane, it’s not the best place for them, and it’s not the best place for the community,” Sunderland said.

“So, it’s incumbent on the community, like in Louisville, where they are looking for an alternate space, to say you can’t camp here because it’s interfering with this business,” he said.

“It’s interfering with this public park. It’s creating a situation in our community where mothers don’t want to take their children shopping because of what’s going on in a particular area. And it’s becoming a nuisance to the community in some measure, but it’s also becoming unsafe, because these areas can’t be properly cleaned or secure.“

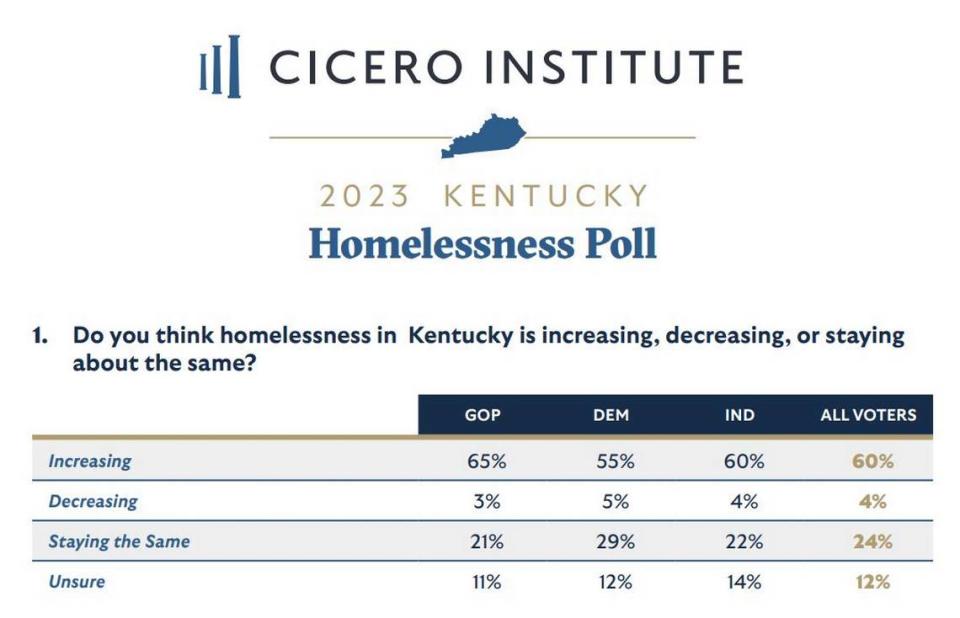

As part of its lobbying efforts in Kentucky this winter, the Cicero Institute has released a poll of 1,507 likely Kentucky voters that it surveyed in late December, asking them about their views on homeless people in public places.

Fifty-nine percent of the respondents favored a statewide ban on panhandling, according to the poll. Fifty-six percent supported a ban on homeless camps in the streets and other public places. Thirty-nine percent said they always or usually avoid going into areas where homeless people are living on the streets.

However, the National Homeless Law Center of Washington, D.C., says that criminalizing people who sleep in public hasn’t solved the problem of homelessness. Places that have started doing it are only shoving homeless people out of view, to the fringes of cities, the center says.

In Austin, Texas, which has a two-year-old public camping ban, as well as soaring housing costs, the number of homeless in the city steadily increased to more than 5,500 as of last fall, according to a local count.

But many homeless people simply drifted away from downtown neighborhoods for parks, nature preserves and other green spaces farther out, away from police scrutiny but also the social services they need.

Austin police officers clearing urban street camps say they often have nowhere else to send the homeless people they’re evicting, the Texas Tribune reported in 2022.

“With these laws, you’re putting law enforcement on the front lines of the homeless crisis, and they don’t want to be there,” Eric Tars, senior policy director at the National Homelessness Law Center, told the Herald-Leader

“In many ways, you’re really setting them up for the next viral body-cam video incident where you’ve sent an officer into a camp where people are living, often sleep deprived, probably stressed, possibly with mental illness, and you’re telling him to go break up their camp, take their things and maybe arrest them. That’s not going to end well for anyone.”

Worse, the expansion of a state’s “stand-your-ground” law against homeless people seen as threatening raises “some really chilling prospects,” Tars said.

“This basically authorizes vigilante justice against unhoused persons if they are sheltering themselves on private property,” he said. “To call that a public safety bill just defies comprehension.”

The Lexington police department said it had no comment on House Bill 5. The Kentucky State Fraternal Order of Police has endorsed it.

Housing First starts with a roof

House Bill 5’s restrictions on Housing First, a program model that prioritizes putting people in permanent, subsidized homes ahead of mental health or addiction treatment, would cost Kentucky millions of dollars a year in federal funds for affordable housing, state and local housing officials say.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development cites evidence-based studies supporting the Housing First model, and it requires housing programs it funds to run on that model, said Charlie Lanter, Lexington’s commissioner of housing advocacy and community development.

“We would no longer be competitive for any new funds,” Lanter said. “And when I say we, I mean the entire state of Kentucky.”

The city of Lexington serves 234 people annually through nine different housing programs, “all operating on a Housing First model,” said Jeff Herron, the city’s homeless prevention manager.

The Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government launched its first Housing First program a decade ago through a $250,000 grant to the Hope Center, taking 18 carefully screened men and women off the streets and out of shelters and putting them into their own subsidized apartments.

Once the people were permanently housed, caseworkers offered them an array of services, including mental health care and addiction treatment, rather than the previously traditional model of requiring people to undergo treatment before they could be placed in housing.

All but one of the early participants accepted the offer of help.

The University of Kentucky Center for Business and Economic Research studied the first two years of Lexington’s Housing First outreach and declared it a success.

In a 2018 report comparing the early participants to control groups, UK researchers said Lexington saved thousands of dollars per permanently housed person on reduced shelter demand and fewer trips to the jail and hospital, to say nothing of incalculable “improvements in quality of life” for people no longer struggling to survive outdoors.

But the Cicero Institute opposes Housing First.

The think tank says that two decades and 200,000 permanent, subsidized housing units after the model was adopted by the federal government, many American cities still grapple with “street homelessness.”

Housing First fails because it does not first address the mental health and addiction problems that plague so many chronically homeless people, the Cicero Institute says.

“These individuals are reluctant to accept assistance without mandates and requirements, and a house without such mandates will not encourage use of these services,” it states on its website.

Echoing the think tank, Hodgson, the House bill’s sponsor, said, “Every case study I have looked at in the last year suggests Housing First is an abject failure and resulted in more unsheltered homeless and exorbitant costs to the taxpayers.”

‘Not a crime to be homeless’

Families live in their vehicles in Lexington parking lots because they have nowhere else to go, which would qualify as camping under the House bill, said Kim Bottom, 58, speaking at the Catholic Action Center, where she’s currently staying.

“Sleeping outside in a car or whatever they’ve got to do — I mean, it’s wrong, but they’ve got to do it sometimes,” Bottom said.

Locating an empty shelter bed in Lexington can be difficult on any given night, she said.

“I was lucky that I had somebody pulling for me. But normally, it’s really, really super-hard to find a place,” Bottom said. “There’s only one women’s facility in the whole city and one (women with families) facility. They really need to do something. They need to have another Salvation Army or something.”

Another woman temporarily staying at the Catholic Action Center, Julia Davis, also 58, said she was the victim of a robbery that wrecked her finances and nearly put her out on the street. She desperately wanted to avoid that fate because “Lexington is kind of rough,” Davis said.

The House bill would imprison people who need help, not punishment, Davis said.

“It’s really not a crime to be homeless. It can happen to anybody under different circumstances,” Davis said. “Build another homeless shelter. There’s enough money around here with all of this horse money, this tobacco money, you could build another homeless shelter instead of putting people in jail.”

“This bill should not be passed. It’s wrong,” she added.