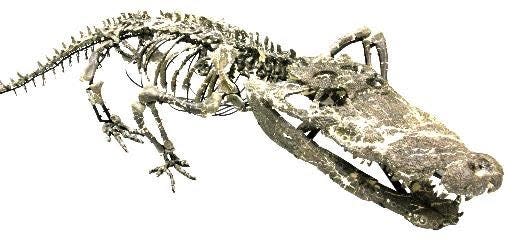

This crocodile ancestor discovered in Wyoming shows how it became the predator it is today

Researchers have discovered the fossil of a 155 million-year-old relative of the crocodile in Wyoming, and they say it shows how the species evolved into the ferocious animal it eventually became today.

Crocodiles could be considered living dinosaurs, as they are one of the few species that survived the asteroid impact over 65 million years ago, and they are still around to this day. Currently, there are 24 different types of crocodilians, according to the Crocodiles of the World Zoo in the United Kingdom.

Today, crocodiles like the saltwater crocodile usually reach up to 17 feet and weigh over 1,000 pounds, according to National Geographic. This ancient crocodile, which was discovered in 1993 and is named Amphicotylus milesi, was around 7.5 feet long and weighed around 500 pounds. It ate fish and small dinosaurs.

When you think of a crocodile hunting prey, you think of it leaping out of the water, viciously attacking its prey and bringing it into the water to eat. But when the dinosaurs were roaming the Earth, the early ancestors of modern crocodiles had a tough time doing so because they were still adapting to being water creatures and could drown themselves.

"We suspect that the animals that were crocodilians had a much more difficult time trying to ambush prey and bring them in water because the chances of trying to struggle with a prey underwater and then ingest water in your lungs were really high," said Michael Ryan, professor of earth sciences at Carleton University in Ontario.

However, what researchers discovered in the Wyoming fossil was this ancestor had a valve-like extension in the back of its throat that allowed it to shut down the airway passage from its nose to its lungs. By having this body part, the crocodile would be able to eat prey while underwater, as long as its nose was above the surface.

The team's findings were published in the Royal Society Open Science journal on Wednesday.

"It allows them to ambush prey and pull them underwater without actually drowning while they're there trying to fight with prey," Ryan said, who is a co-author of the study along with a team from Hokkaido University in Japan.

'Horned crocodile-faced hell heron?': New species of dinosaur unearthed by fossil hunters

More: Crocodile lives at this Florida golf course — and is there to stay

Ryan added that the discovery opened up "a whole new evolutionary realm" of crocodiles and offers answers on how they are still around today.

"We think that it might have been at least one of the things that contributed to crocodiles being one of the most successful long-lived group of land vertebrates," he said. "If you look at their evolutionary history from when they originated back in the Triassic (period), they have an unbroken evolutionary history that goes for more than 250 million years."

Ryan said this discovery can hopefully lead to learning more about the connection between crocodiles and dinosaurs, but most importantly, helped understand crocodiles today, how they live and how to help them survive any potential climate changes.

"Without understanding the deep past, it's going to be very difficult to understand what is going on today," he said.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Crocodile ancestor in Wyoming shows how the species is still around