The Crucial Heart That’s Missing From Apple TV+’s Adaptation of the Bestseller Lessons in Chemistry

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This post contains spoilers for Lessons in Chemistry.

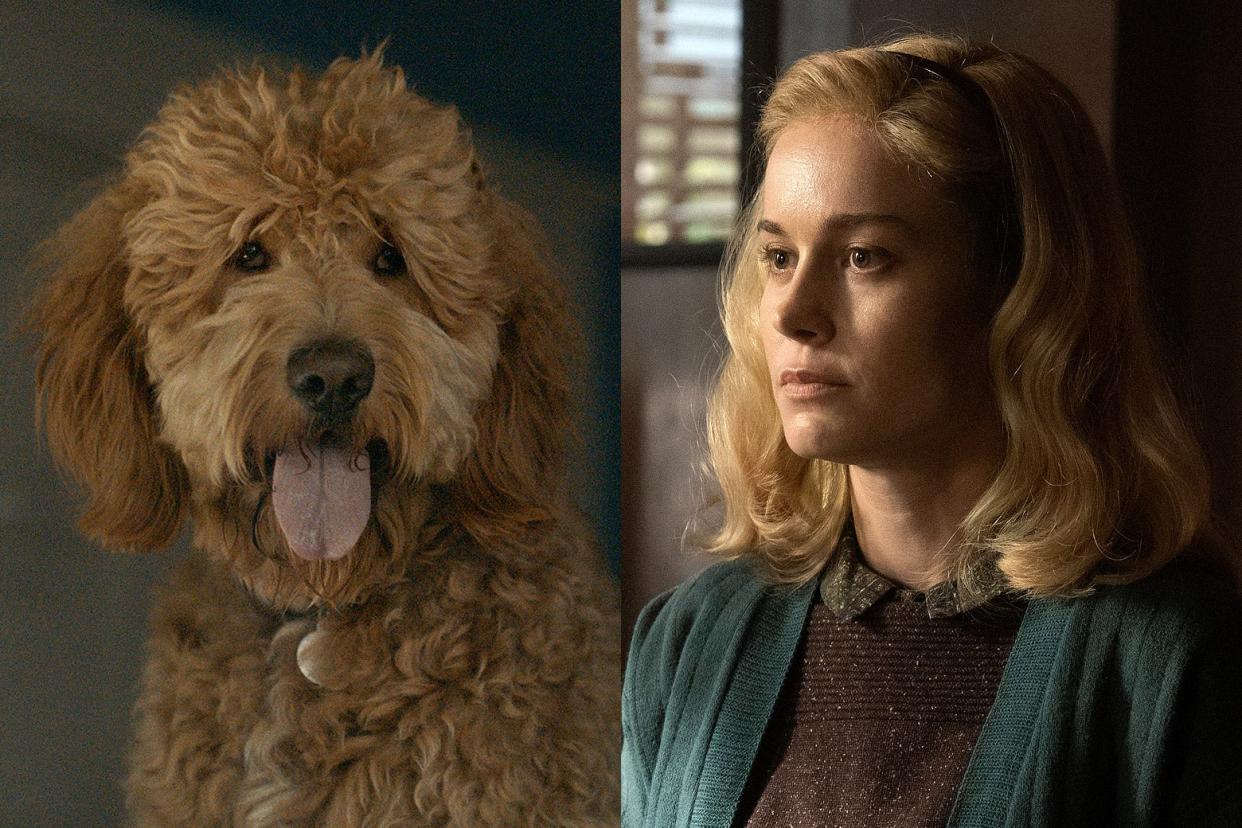

Lessons in Chemistry, the Apple TV+ adaptation of Bonnie Garmus’ bestselling novel of the same name, is less than faithful to its source material by design. In trying to translate for the screen the story of Elizabeth Zott (Brie Larson), a woman in the 1950s whose experiences with sexism prompt her to leave behind the world of science and become a popular cooking television show host, the show alters much from the book. These modifications aren’t bad per se, although I felt that some were unnecessary—others may disagree—but there’s one that will immediately stick out to any fan of the novel. Yes, I’m talking about the dog.

It was obvious from the start that one of the best aspects of the book was one that the show could never nail. Six-Thirty, Elizabeth’s dog, is a big part of what makes the novel so charming (that, and the fact that it’s obviously affecting to see a smart, capable woman know what she wants and behave as such, despite the world’s ideas of how she ought to move through it). Six-Thirty—in the book, named for the time of day when he, as a stray dog, follows Elizabeth home; in the show, named for the time he always wakes Elizabeth up—serves as one of the novel’s main points of view. We learn of his most intimate thoughts and of his history, including an ejection from military canine bomb-sniffing training that led him to wander around unclaimed. This is all delivered in perfect English that, while quirky, admittedly does not feel particularly caninelike but is easily explained away in the novel by the assertion that Six-Thirty is an unusually smart dog, as evidenced by his ability to learn almost 1,000 words taught to him by Elizabeth.

But Six-Thirty’s point of view isn’t just a fun, rarely seen gimmick: It’s also important to Garmus’ depiction of the human characters and the way they process grief, guilt, and understanding. This is seen most clearly in one of the most pivotal plot points in the book: the death of Elizabeth’s partner, Calvin. In the novel, in accordance with a new law requiring dogs to be tethered to their walkers, Elizabeth gives Calvin a leash to use on his morning runs with Six-Thirty, despite man’s and dog’s insistence that the leash isn’t necessary. A leashed Six-Thirty, frightened by a loud noise in front of a parking lot, tries to run away from Calvin, resulting in Calvin tripping and hitting his head right as a vehicle leaves the parking lot. The car runs over his prone body, and Calvin is killed.

Elizabeth and Six-Thirty both feel directly responsible for Calvin’s death. This affects Six-Thirty’s mindset throughout the story, inspiring his overprotectiveness of Elizabeth and her precocious daughter, Mad (Alice Halsey), whom Six-Thirty cutely refers to as “the creature.” This culminates in Six-Thirty overcoming his fear of explosives and detecting a bomb in an audience member’s purse during a taping of Elizabeth’s cooking show, ultimately saving her life. It couldn’t have happened without the loss of Calvin and the growth that the tragedy sparked in Six-Thirty. The book shows us that actions and emotions have consequences and that those effects ripple out to a wider community.

I knew that the television adaptation would try to convey Six-Thirty’s story, and try it did. In the show, Elizabeth gives Calvin a leash merely for extra safety. One morning, Six-Thirty, still acclimating to the leash, has a tug of war with Calvin, who wants Six-Thirty to cross the street with him. This leads to Calvin stepping into the street, right into the path of a bus. It may not sound radically altered from the book’s version of his death, but the crucial difference is in how the two works approach the question of guilt. To be fair, the show does dip a toe into the inner workings of Six-Thirty’s mind. In Episode 3, “Living Dead Things,” B.J. Novak voices the inner monologue of Elizabeth and Calvin’s scruffy companion. We hear Six-Thirty’s backstory in his own voice, including how that affects his feeling that he failed to protect Calvin—which, it should be noted, is different from feeling directly responsible for his death, as the book’s Six-Thirty does. However, the dog’s voice isn’t present throughout the show like it is in the novel, woven into moments both big and small. Though it’s much appreciated, it’s not a constant in the way that most readers probably wish it were.

But how could it be? It was clear from the start that this is simply one of the sacrifices a screen adaptation of Lessons in Chemistry would have to make. A miniseries has limited screen time to convey a story, and it makes more sense to focus on telling Elizabeth’s from her point of view. And even if the show had thoroughly incorporated more of Novak’s voice-over, it might have felt too hokey: Inner monologues are one of the things screen adaptations of novels often whittle down—they’re not the most conducive to a visual format. Still, I wish the show had incorporated more one-off lines from Novak. Or, at the very least, that the dog’s quirky use of language had stayed. (The dog refers to Mad as a “baby” in the show, versus the book’s “creature.”) Something, anything, to nod at the significance of Six-Thirty’s role in the novel as a narrative device, as an emotional linchpin, as a fresh look at life beyond the rigid viewpoint of Elizabeth Zott’s. Lessons in Chemistry is still a pretty good show, especially if you’re unfamiliar with the source text. But watching it, you might be struck by the distinct feeling that something about the story’s appeal still eludes you—a sign that the TV adaptation perhaps didn’t fully understand what made readers fall in love with the book, that it misunderstands, at times, where the story’s heart is.