CT’s ‘baby bonds’ funding sufficient for 15K children born every year for next 12 years

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Each of the 7,810 babies to born to mothers on Medicaid in the last half of 2023 in Connecticut are potential beneficiaries of a $3,200 “baby bond” projected to be worth at least $11,000 when they turn 18, beginning July 1, 2041.

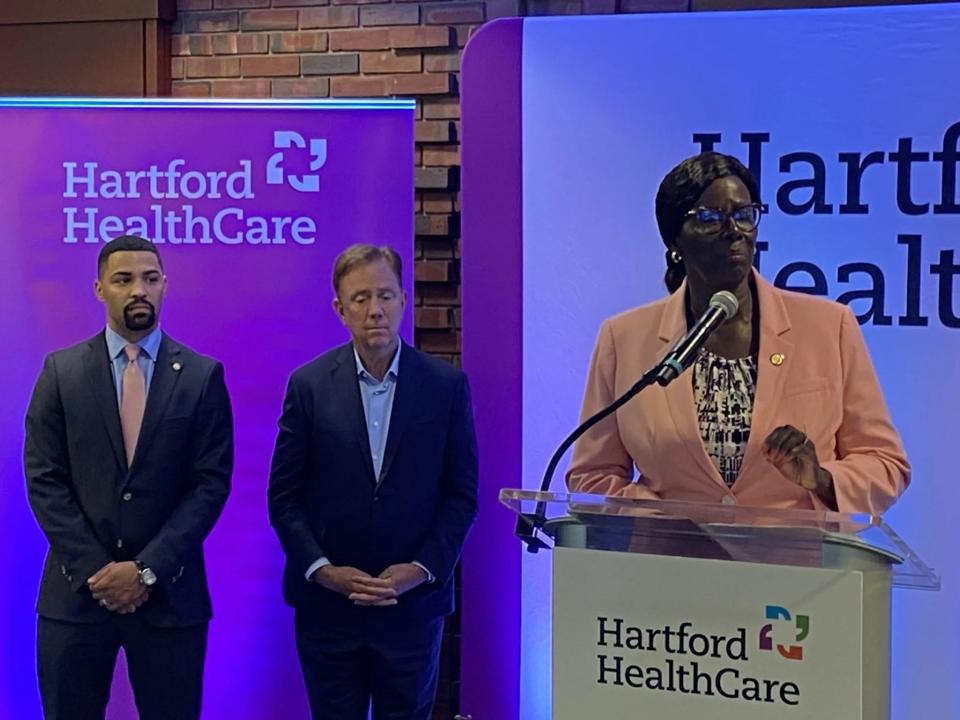

Treasurer Erick Russell and Andrea Barton Reeves, the commissioner of the Department of Social Services, gave the first update Wednesday about the state’s first-in-the-nation experiment exploring if a financial stake for education, a housing down payment or business opportunity can mitigate generational poverty.

All but five of the state’s 169 cities and towns are home to babies automatically enrolled for a baby bond, a reminder that financial need is widespread in a state that reliably ranks high in per capita income and financial inequality. The majority of those eligible live outside Connecticut’s five largest cities.

To cash in on a baby bond, an enrolled recipient must be between the ages of 18 and 30, pass a financial literacy test and be a Connecticut resident. The proceeds are intended to leverage opportunities that could generate the family wealth, modest or otherwise, that homeowners now pass from generation to generation.

Depending on the age at which a recipient accesses the money, the bond could be worth as much as $24,000, Russell said. Enrollments began on July 1, 2023.

“You want to build wealth in this society, nothing is more important than freeing yourself from debt and then [achieving] ownership,” said Gov. Ned Lamont, the beneficiary of multi-generation wealth and husband of a prominent venture capitalist.

Russell, who played a pivotal role in striking a deal with an initially skeptical Lamont to fund the bonds, acknowledged the limits of what a $24,000 windfall might bring in a state where public-college tuition already averages more than $14,000 for one year and the median house price exceeds $400,000.

“We understand that baby bonds by itself is not the silver bullet, and it’s not going to solve all of our problems. What we do know is that this is a piece to a much larger puzzle,” said Russell, a Democrat elected in 2022 to oversee more traditional investments such as pension funds.

Unclear is how more pieces of that puzzle will slip into place in Connecticut, a state with fiscal controls that have directed a significant share of budget surpluses into a rainy-day reserve fund and paying down one of the largest unfunded pension liabilities in the U.S.

The Lamont administration is committed to staying within those fiscal controls and instead has focuses on efficiencies, such an interagency effort to combat rising homelessness and one-stop Opportunity Centers operated by the Department of Social Services.

Russell said coordinated services — some which might not now exist — will be needed if baby bond recipients are to fully benefit.

“How we support those kids along the way will go a long way in determining how prepared they are to seize in this opportunity,” said Russell, who added that he has organized a working group on the subject.

The 7,810 babies born over six months to mothers receiving HUSKY, the state’s Medicaid program, is roughly consistent with expectations that 15,000 more children would become eligible and automatically enrolled each year. Bridgeport had the most, with 798, followed by: Hartford, 621; Waterbury, 615; New Haven 560; and Stamford, 376.

Nearly 5,000 of those enrolled were from suburbs and smaller cities.

“For example, in Ansonia there are 75 who are enrolled. In Bethel, there are 33. In East Haven, there are 59. In Killingly, there are 44,” Barton Reeves said. “In Meriden there are 229 children born who are eligible,” she said. “In New London, there are 129.”

The update came nine days after the 60th anniversary of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s first State of the Union Address, when he declared “all-out war on human poverty and unemployment,” an enemy that has proven resilient and well-entrenched in the decades to follow.

The official poverty rate dropped from 19.5% in 1963 to about 10.5% in 2019, though experts disagree if the number accurately captures poverty. One of those experts is Matthew Desmond, a Princeton sociologist and author of “Poverty, by America,” a book that Barton Reeves recommended.

The recommendation came despite Desmond’s argument that America has grown complacent with a double-digit poverty rate and that state and federal governments no longer are pressing for a victory in LBJ’s war.

“I think Connecticut is doing a lot of the right things,” Barton Reeves said.

But she acknowledged there are fundamental challenges posed to anti-poverty agencies by a shift in the economy to service jobs that pay poorly and offer no benefits.

“I recommend that book, because it was really transformational in the way that I’ve thought about poverty,” she said. “The job that I have means that every single day I have to think about the war on poverty. I go to every office, and I see them and I understand to the best that I can that this is a real struggle for 1.2 million people in the state that we serve.”

Lamont slowed the implementation of the baby bonds, which was proposed by Russell’s predecessor, Shawn Woodwen, and originally was to be financed by $600 million in borrowing — $50 million a year over 12 years.

Ultimately, the state was able to access nearly $400 million that had been set aside in a reserve fund to guarantee repayments after Connecticut restructured its teacher pension debt. The reserve no longer was necessary after the state used $2.7 billion in surplus funds to beef up the pension fund.

Russell said the funding was sufficient to provide baby bonds to about 15,000 children born every year for the next 12 years.

Mark Pazniokas is a reporter for The Connecticut Mirror (https://ctmirror.org). Copyright 2024 © The Connecticut Mirror.

This article originally appeared on The Bulletin: Conn. baby bonds program to help Medicaid families, Lamont on board