Cuba’s economic crisis is worse than after fall of the Soviet Union, economists warn

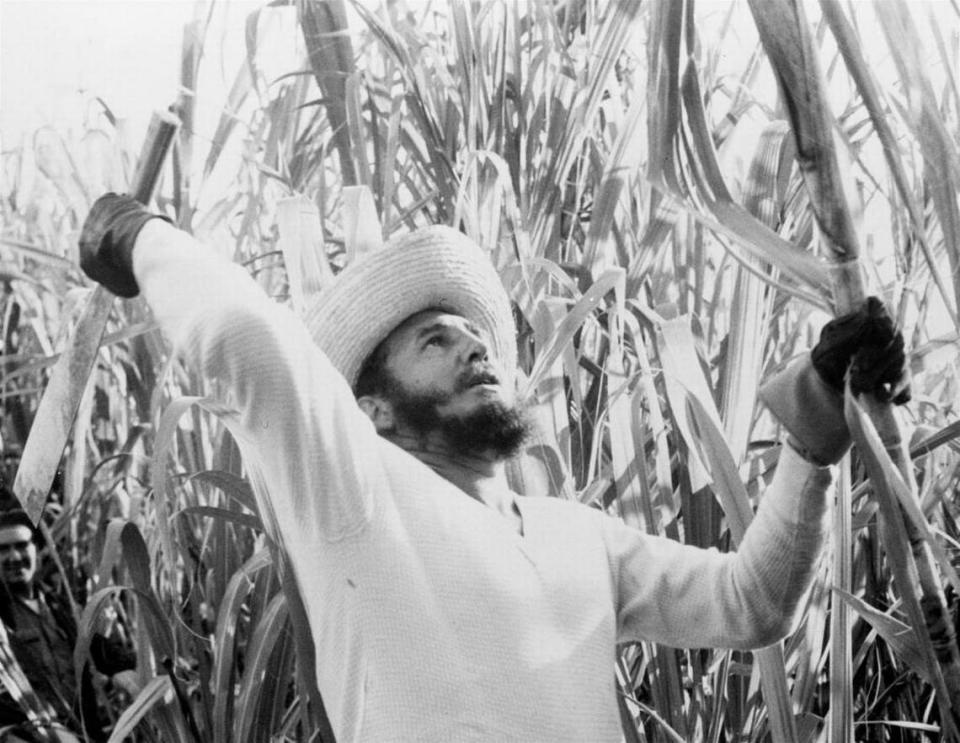

Cuba, which for decades was one of the largest exporters of sugar in the world, now has to import sugar to meet its domestic demand.

Six decades after the Cuban Revolution, the country is again undergoing a severe economic crisis, this time worse than the infamous “Special Period” in the 1990s, as the economic downturn that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union is known. But Cuba is also experiencing a boom in private enterprise, a contrasting reality fueling more inequality, economists gathered in Miami to analyze the situation on the island said.

“The economic crisis in Cuba that started around 2019 has worsened, approaching or surpassing the magnitude of the severe crisis of the 1990s,” Carmelo Mesa Lago, the most prominent expert on the Cuban economy, said at the annual conference of the Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy at Florida International University.

Using official Cuban data, Mesa Lago provided a devastating picture of the situation: Cuba’s economy was already in the red when it contracted almost 11% in 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic and, unlike its Caribbean and Latin American neighbors, it is not showing signs of recovery. Almost everything — from tourism to exports, mining and manufacturing – has declined to alarming levels.

During the pandemic, the island’s budget deficit reached 17 % of GDP, prices grew 401% in 2021, and the Cuban peso depreciated so much that 4,000 Cuban pesos, the medium state salary, is now worth about $16.

Agriculture, in particular, “is a total disaster,” Mesa Lago said.

Sugar crop falls drastically

From a peak of 8,5 million tons of sugar in 1970, the country produced only 473,000 tons in 2022 — less than the average yearly production more than a century ago, during the 10-year war for independence that began in 1868. Because the government had contracted to export 400,000 tons to China, and Cuba’s internal consumption is around 600,000 tons, the government had to buy sugar in Brazil to fulfill its obligations to Beijing, he said.

This year, Cuban officials said the sugar harvest will only produce 350,000 tons.

Sugar is not the only thing missing from Cuban tables because agricultural production, livestock, and fishing have all plummeted in the past five years and, so far this year, have decreased another 35%.

The production of pork, beans and rice, Cuban food staples, have all suffered. In 2021, pork production, for example, decreased 60%, followed by an 18.6% decline last year.

Citing a lack of financial resources, Cuban authorities are now importing about a third of what they did in the past to distribute to the population through ration cards. And because of disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, the same amount of money can buy less than five years ago.

The current crisis, marked by widespread food shortages, the abrupt depreciation of the Cuban peso and sharp inflation, has not hit everyone the same, said Ricardo Torres, a Cuban economist who is a faculty fellow at American University in Washington, D.C.

Sudden banking cash-withdrawal limit threatens private sector and food imports to Cuba

People who don’t receive remittances from abroad — around 40 percent of the population, according to some estimates — or have no other access to dollars, particularly state-salaried workers and pensioners, feel the consequences harder.

“For some people, it’s far worse than it was back” during the Special Period, Torres said. Cuban society has become more unequal and lacks the safety net in place at the beginning of the 1990s, he added. The current crisis “hits Cuba after almost three decades of a permanent crisis,” he said.

Torres also questioned why, “even in the middle of a crisis,” the government continued investing large amounts of money in tourism and building more hotels – a sector mostly handled by companies belonging to a conglomerate controlled by Cuba’s military — when the numbers were showing very little return on the investment.

Official Cuban figures show that tourism declined even before the pandemic. From 2017, when tourists visiting the island peaked at 4.6 million, to 2021, visitors decreased by 92 percent. In 2021, the hotel room occupancy rate reached a dismal 5.7 percent. In 2022, that number was still critically low, at 15.6 percent.

Cuba’s minister of the economy, Alejandro Gil, recently said the economy grew 1.8% last year, which Mesa Lago said “is very difficult to believe.”

Private sector is “another world”

But there’s “another world out there” that official numbers are not capturing, Cuban economist Omar Everleny Pérez said, referring to the growth of small and medium enterprises known by the Spanish acronym pymes.

Even though remittances from abroad have decreased after the U.S. imposed sanctions in 2020, Cuban Americans are buying food for their families directly from private businesses on the island, which gets delivered “in less than 48 hours” to their relatives there, Perez said.

Pérez, a former professor at the University of Havana who now works with the Christian Center for Reflection and Dialogue in the Cuban city of Cardenas, said private businesses and grocery stores are proliferating on the island and sell American products like Goya foods and Philadelphia-brand cream cheese.

“In my neighborhood, we don’t go to the government stores; we go to the private stores... The prices are high, but they are still selling every day,” he said.

Pérez said private businesses are importing food, construction materials and other products from the United States “because there are commercial companies here in Miami that, if you give them the money, they fill a [cargo] container and send it to the port of Mariel,” west of Havana.

Exceptions in the U.S. embargo authorize exports of food to Cuba. And other regulations allow U.S. companies to sell other products if those go to the private sector, not the state.

How Miami companies are secretly fueling the dramatic growth of Cuba’s private businesses

While the growth of private enterprise is a recent development — Cubans were not allowed to own private businesses till 2021 — some entrepreneurs are making significant amounts of money, primarily through food imports, raising questions among the population about excessive profits amid a crisis.

“There are people making money through food imports,” Pérez said, telling the story of an unnamed business owner he said has imported 34 cargo containers in just six months and made $300,000 in profits.

Government officials have attacked these new private businesses for primarily becoming importers instead of producing goods. However, Perez said the criticism is unfair because this is a relatively recent development, and the state still controls most of the production facilities and resources.

“I think the pymes will contribute to the country’s development by generating employment and developing some activities, but you cannot ask them to solve the problems of Cuba at this initial stage,” Perez said, adding that this new part of the economy will generate more inequalities, even though the enterprises are not the cause of existing disparities on the island.

The return of the private sector in Cuba – even under tight government control – has generated a heated debate in Florida and Cuba. Human-rights activists said it is impossible to own a private business without connections in the government and that Cuban authorities are using the pymes as a diversion from addressing demands of political change coming from the population.

Mesa Lago agreed that Cuban authorities seem to be moving towards “the inefficient Russian model of oligarchic capitalism.” But he also said he believes the pymes “are important and positive. They should not be attacked; they are a private sector, and that’s what we want.”