In Cuba, trend seen away from eccentric names

HAVANA (AP) — Yanitse Garcia has spent three decades correcting people on the pronunciation and spelling of her first name.

So when her firstborn came into the world three years ago, Garcia decided to save her daughter a lifetime of grief by choosing a simple name that everyone knows and which flows off the tongue: Olivia.

"What I liked about Olivia is precisely that it wouldn't be a bother for her," Garcia, a 32-year-old specialist in foreign languages, said with a laugh. "It works for both Spanish and English, and nobody ever will misspell it."

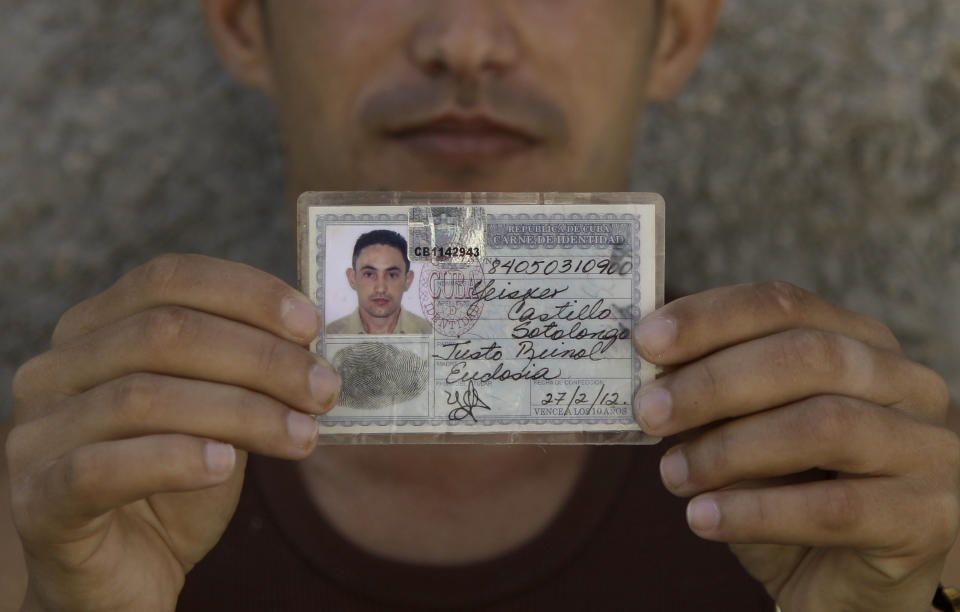

Garcia is part of Cuba's so-called Generation Y, the thousands upon thousands of islanders born during the Cold War whose parents turned tradition on its ear by giving them invented monikers inspired by Russian names like Yevgeny, Yuri or Yulia. The phenomenon was so prevalent that dissident writer Yoani Sanchez chose "Generation Y" as the title of her well-known blog; her counterpart on the cyber-ideological battlefield is a pro-government blogger and tweeter who uses the handle Yohandry Fontana.

More than two decades after the fall of the Iron Curtain, Cubans are increasingly returning to more traditional handles for their kids, saying they believe it will better suit them personally and professionally when they grow up. More and more, names like Maria and Alejandro are replacing the likes of Yoleissi, Yuniesky, Yadinnis, Yilka, Yiliannes, Yonersi, Yusleibis, Yolady, Yudeisi or Yamilka.

"The Y thing was like a fever, a boom. It was (about) doing something different from the monotony of the Pedros and the Rauls," said Carlos Paz Perez, a sociolinguist at Miami Dade College and the author of a dictionary of Cuban slang. "But now that has passed and there is a tendency to recover traditional names."

Decades ago many Cuban parents named their kids after other family members or hewed to the common practice in the Spanish-speaking world of honoring the Roman Catholic saint associated with a child's birth date.

There were only a smattering of eccentric monikers back then, said Uva de Aragon, a retired Cuban-American academic and writer born in 1944 in Havana. De Aragon's own name was inspired by her grandfather, Ubaldo, and she also recalled a family friend named Olidey after the English "holiday."

After the 1959 revolution and Cuba's subsequent self-declaration as an officially atheist state, folks really started getting creative.

"As many people stopped baptizing their children, it was no longer necessary to pick a name that was in the calendar of saints," de Aragon said.

Inventions like Vicyhoandry began creeping into state birth registries, as did names such as Daymer — a combination of Daniel and Mercedes — and backward renderings as in Airam instead of Maria. So too did curious English-language borrowings: More than a few Cubans can say with a straight face that Danger is not their middle name, but their first.

Meanwhile, Cold War geopolitics also inspired names such as Katiuska, after the Russian-made Katyusha missile launchers. Other kids were called Che, Stalina or Hanoi.

But it was the Generation Y phenomenon that was uniquely Cuban, and brought out many parents' creative instincts. Consider the name Yotuel, a mash-up of the Spanish-language pronouns "yo," ''tu" and "el," or "I," ''you" and "he" in English.

Y-fashion spread overseas through migration to Florida and elsewhere, and some of the most famous examples are found on Major League Baseball rosters in the names of defected stars Yasiel Puig and Yoenis Cespedes.

While there's no public data available, experts and parents alike have noted a clear trend away from Y-based and other eccentric names in recent years.

An AP review of one high school class list in Havana turned up a dozen unusual names including Yuneysi, Luzaniobis, Alianis and Dianabell, among 40 students. Meanwhile a first-grade class of 20 students had just two, Raicol and Nediam — apparently the English word "maiden" spelt backward.

"The phenomenon in Cuba got out of control, it got out of hand. Names are also the image of the country," said Aurora Camacho, a researcher at the governmental Institute of Literature and Linguistics of Cuba who called for legal guidelines on the naming of children.

She's not alone. Eccentric names have been popular elsewhere in Latin America and at times provoked a backlash.

In 2007, Venezuelan authorities unsuccessfully pushed a bill that would have outlawed "names that expose (children) to ridicule, be they extravagant or of difficult pronunciation" after two Supermans were discovered in the registry. A similar proposal failed in the Dominican Republic in 2009.

This month, the Mexican state of Sonora banned 61 oddball names that had been found at least once in state registries. They included Facebook, Rambo, Circumcision, Lady Di and Juan Calzon, or "Juan Underpants."

Recent months have seen articles in Cuban official media warning of the need to regulate naming practices and urging parents to be thoughtful when it comes time to register their newborns.

But the simple ebb and flow of naming fashions seems to be turning the tide even without the heavy hand of the government.

Yanitse Garcia, whose husband is Raisel — a cross between Raimundo and Elena — said all of her daughter Olivia's cousins also have traditional names: Ernesto, Gabriela, Carlos and Christian.

"I think there was a saturation," Paz Perez said.

___

Andrea Rodriguez on Twitter: www.twitter.com/ARodriguezAP