Cubans who lived through Castro's literacy program frustrated by Bernie Sanders' praise

MIAMI – There were brief moments when Ana Garcia felt she was doing something good by teaching illiterate people how to read in the Cuban countryside.

It was 1961, and the 17-year-old had been sent out to small, rural towns in a green shirt, green pants and black boots as part of Fidel Castro’s literacy campaign that was promoted as a way to eradicate illiteracy on the Caribbean island.

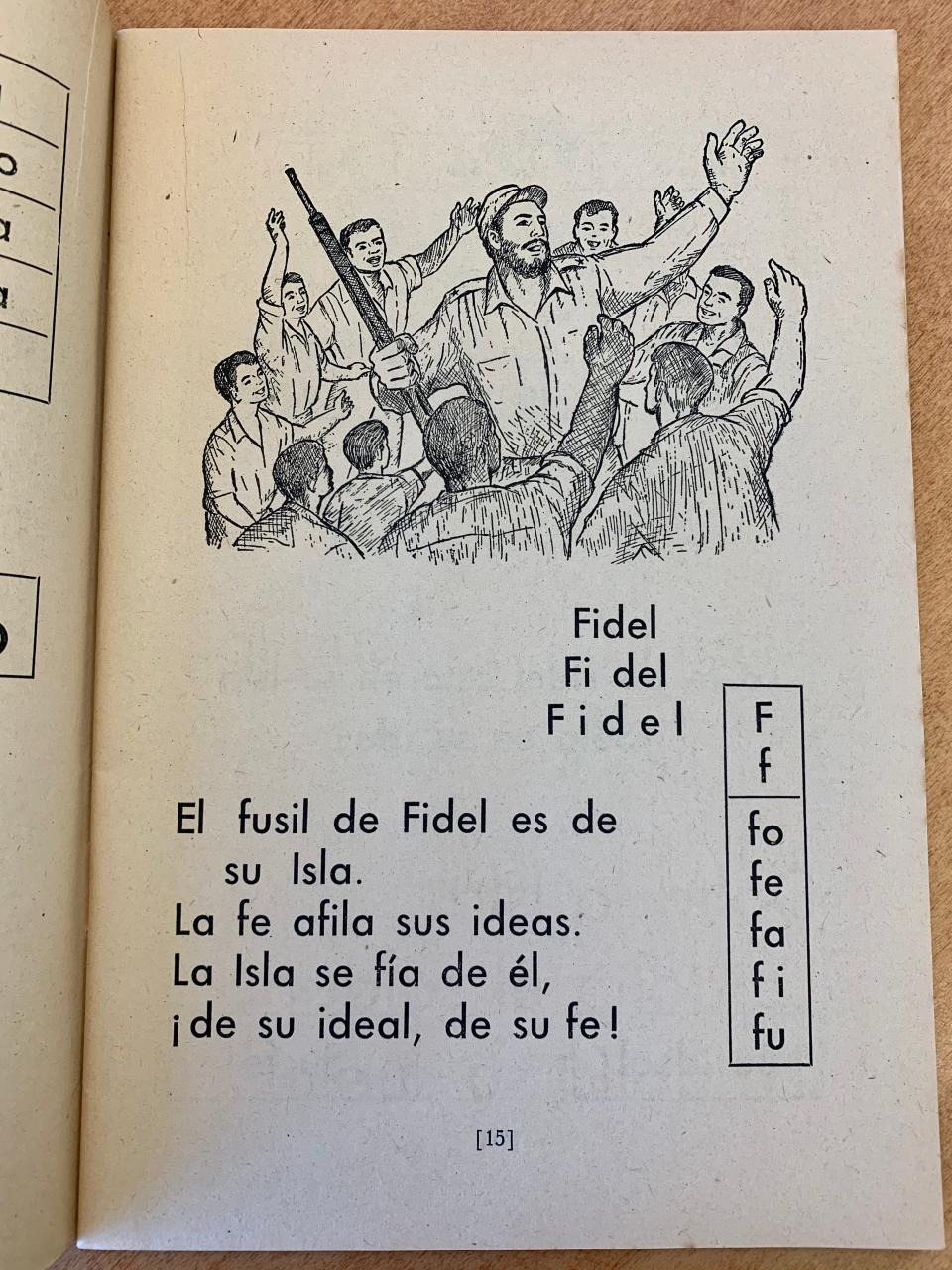

But Garcia knew something was strange the moment she picked up the training materials produced by the government. The teacher’s manual included 76 pages of chapters outlining the glories of Castro's revolution and the dangers of imperialism and just 20 pages of suggested vocabulary words. Instead of the usual ABCs, the student’s manual featured “F” for Fidel, “R” for his brother, Raúl, and “V” for victory.

Within three months, Garcia’s father had seen enough and arranged for her to be pulled out of the literacy campaign.

“In those moments, when people were learning, of course it felt good. I love teaching and that’s what I wanted to do,” said Garcia, 76, who left Cuba years later and became a teacher in Miami. “But everything was designed to introduce communism. That was it.”

The history of that program will be revisited as the presidential campaign makes its way toward the critical swing state of Florida.

After losing Michigan and other states on Tuesday, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders is desperate for a win in the Sunshine State. But he's already being pummeled there by former Vice President Joe Biden in the polls — a Florida Atlantic University poll conducted last week had Biden up 61-25 over Sanders in the state.

And now Sanders is preparing to face the Cuban American exiles that he angered when he repeated his praise for Castro's literacy program. During a Feb. 23 "60 Minutes" interview that has become required viewing in South Florida, Sanders said Castro "totally transformed the society" in Cuba in part through his literacy campaign.

"Is that a bad thing?" he said.

Election 2020: Bernie Sanders will keep pursuing presidential nomination with eyes on Sunday debate, despite narrow path ahead

Those who were living in Cuba at the time say Sanders' assessment is wrong on multiple counts. They say Cuba's literacy rate was already among the highest-ranking in Latin America when Castro took over. And more importantly, they say the literacy campaign Castro implemented in 1961 was more political indoctrination than basic education.

"You can't divorce (the literacy campaign) from the political agenda that Castro had," said Yuleisy Mena, a Cuba native and high school history teacher in Miami who has been interviewing participants in the 1961 literacy campaign as part of her Ph.D. dissertation at Florida International University. "This was a mass mobilization used for indoctrination."

That viewpoint explains why so many Cuban Americans in Florida — and Venezuelans and Nicaraguans who fled socialist dictators in their homelands — are suspicious of any political candidate who even mentions socialism. And it explains why Sanders has won the Hispanic vote in California and Texas, but is trailing Biden among Hispanics in Florida 48% to 37%, according to a Telemundo poll released Wednesday.

When Castro's bearded guerrillas marched into Havana on New Year's Day 1959 to claim power over the island, Cuba's education system was fractured but doing well when compared with other Latin American nations.

Carmelo Mesa-Lago, a professor emeritus at the University of Pittsburgh who has studied Cuba for decades, said the last census in Cuba in 1953 revealed that 76.4% of the population was literate. He estimates literacy rose to about 79% by 1958, the year before Castro took power, which placed Cuba fourth in Latin America.

He said Cuba ranked equally high on a number of other health and education indicators, including the lowest infant mortality rate in all of Latin America. While there was room for improvement in each area, Mesa-Lago said those metrics show how Sanders' assessment of a country in desperate need of reform was flawed.

"That story is not true," he said. The data "shows that Cuba was positioned very high in Latin America in terms of education and health care."

The literacy data did show one glaring gap in Cuba's educational system. The 1953 census found that 88.4% of people living in Cuba's cities were literate, but only 58.2% of people living in rural areas could read and write.

That's where Castro focused his efforts, a sentiment that was lauded by the United Nations and others in the international community. But for those who experienced it in Cuba, the educational push was confusing from the start.

Fidel Castro: Among world's most influential leaders for a half-century

Jaime Suchlicki was studying at the University of Havana in 1959 when he realized that the history books were quickly being rewritten. Cuba's Independence Day was no longer in 1902, the year that the island broke free from a military government established by the United States. It was suddenly Jan. 1, 1959, the day Castro took power.

"They transformed Cuban history," said Suchlicki, director of the Cuban Studies Institute and a professor emeritus at the University of Miami.

Mario Soto was an 10-year-old living in Havana when Castro took power. By the start of the next school year that fall, he said the government had even changed the math textbooks.

"Instead of 'two cows plus two cows equals four' it was 'two guerrillas plus two guerrillas equals four,'" said Soto, a retired engineer and telecommunications executive who now lives outside Atlanta.

Sergio Rodriguez Puig, who grew up in Ciego de Avila in central Cuba, found similar changes in his workbooks. Just eight years old at the time, he was no longer asked to count up balloons or butterflies, but guns and tanks instead.

"You see the insidiousness of their brain-washing already, in a seemingly innocent math book," said Rodriguez Puig, 67, whose family left Cuba in 1960 after seeing how quickly the revolution was shifting toward communism. He lived and worked for 50 years in New Orleans before retiring to Miami.

The literacy campaign started in earnest in 1961, which the Cuban regime dubbed "The Year of Education." At the core of the program was enlisting 100,000 young Cubans — from age 10 to 19 — to trek into the countryside and teach the farmers, ranch hands and others far from Havana the basics of reading and writing.

But it was clear from the materials used that literacy was only part of the goal. Manuals distributed by the Cuban government, some of which are stored at the University of Miami's Cuban Heritage Collection, show exactly what kind of literacy the government was trying to instill in the population.

The majority of the instructor's manual given to the teenage teachers were chapters that echoed the proclamations coming from the government. The first chapter is titled "Revolution." The second proclaims "Fidel is our leader." Later chapters praise the Soviet Union and bash the "Yankee imperialism" that had exploited Cuba.

"Fidel Castro brings together the best qualities of his people and has immense faith in the wisdom, strength, and courage of the people," reads the second chapter. "We Cubans respect and love the chief who raised the people in arms against tyranny and foreign domination."

The final section of the manual provides 20 pages of vocabulary words and phrases that could be used during lessons. Some are basic: democracy, resources, tourism. Some are militaristic: the art of war, blockade, foreign aggression. Some are surprising: the Associated Press, freedom of the press.

And many are focused on the organizations and people of the United States: the FBI, the Klu Klux Klan, the State Department and "gringo."

The definition for the former Soviet Union describes it as a, "Nation formed by the union of several republics, which have a socialist regime and where there is no exploitation of man by man, since in it the goods of production belong to the people."

While the Cuban government said all the teenagers who participated in the literacy program were volunteers, many Cubans laughed at that assertion, calling it "involuntary volunteerism."

Soto said there was pressure on students to participate in the program and to accept the new lessons being taught in schools. He said that after speaking out in class too many times and being suspected of destroying a picture of Fidel Castro that hung in a classroom, his principal called his mother into the school and delivered a thinly-veiled threat.

"They said, 'If you want, he could also choose to go to a technical school and we can send him to the Soviet Union or East Germany to study engineering,'" Soto said. "That's when my mom got really scared."

Within weeks, the family fled to Florida.

Garcia, the former 17-year-old who taught mostly elderly people in their homes in central Cuba, said she sometimes strayed away from the curriculum, teaching her students to read with whatever other books or newspapers were lying around. But for the most part, she felt she had to stick to the script.

"I was scared," she said. "Imagine, I was a kid. You were dominated by fear."

The most disturbing part for those teachers was the final exam. Mena, the history teacher who has been interviewing teachers in the literacy campaign, said that for many, that meant writing a "thank you" letter to Castro himself.

In the end, those who participated in the literacy program were left torn by what they did. Mena said they all said they enjoyed teaching people the basics of reading and writing. But as the days and months wore on, they realized they were taking part in something different.

"It was a farce and the disillusionment was real," Mena said. "They had to reevaluate the larger context of what they did. Their naivete went away. They saw Cuba for what it was and they saw the new government for what it was."

Bernie setback: Biden racks up more big wins and widens delegate lead, but Sanders says he'll keep fighting

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Election 2020: Bernie Sanders' praise for Fidel Castro angers teachers