The curse of third-party presidential candidates

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A version of this story appears in CNN’s What Matters newsletter. To get it in your inbox, sign up for free here.

The viable third-party presidential option is the fever dream of American politics.

But that won’t stop the Green Party or the Libertarians from fielding candidates every election year. And this year, the centrist group No Labels is trying to achieve ballot access for some kind of third-party unity candidate, although details are not yet entirely clear.

It’s always possible that some unstoppable political force could rise up to upend the two-party system that has traded power during everyone and their grandparents’ lifetimes. Anything is possible!

Yet the evidence is that third-party presidential efforts are doomed to failure and play the role of spoiler rather than viable option. These candidates struggle to get on the ballot in every state. They lack the grassroots turnout operations that get even unengaged voters to the polls. Their support frequently falls dramatically by Election Day.

The third-party track record

There’s been a Green Party and Libertarian candidate every presidential year in recent elections, but they rarely get more than 1% of the popular vote in presidential elections.

Note: Figures below come from The American Presidency Project’s list of presidential elections.

►The recent years in which these main alternative parties do relatively well – 2016 and 2000 – also happen to be years in which the winner of the Electoral College vote does not win the popular vote.

►The most successful third-party candidate many living Americans voted for might have been Ross Perot, who arguably spoiled the 1992 election for Republican President George H.W. Bush and allowed Bill Clinton, a Democrat, to win the White House with just 43% of the popular vote.

►In 1980, the Republican congressman John Anderson ran as an independent and more liberal candidate than Democratic President Jimmy Carter on many social issues, according to a New York Times obituary of Anderson.

That didn’t help Carter, already damaged by Sen. Edward Kennedy’s primary challenge. Anderson got more than 6% of the popular vote, although, like many third-party candidates, he polled much higher earlier in the campaign. Most voters tend to go home to their preferred party on Election Day.

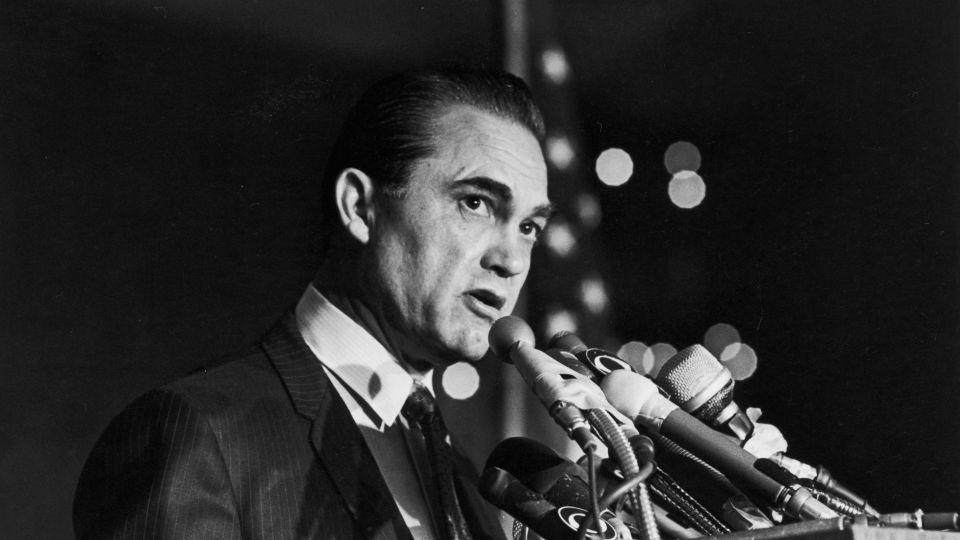

►The last third-party candidate to actually win an Electoral College vote was George Wallace, who in 1968 won five Southern states and 46 Electoral College votes as a segregationist with the American Independent Party. That was the first election after civil rights legislation signaled a realignment of Southern White voters against Democrats.

►The sitting Democratic president in 1968, Lyndon Johnson, decided not to run that year. But you’ll notice that with the exception of 1996, when Perot ran again, all those years with third-party candidates who registered more than 2% in the popular vote – 1968, 1980, 1992, 2000 and 2016 – were years in which the party that controlled the White House lost it.

Conclusion: The evidence is that a strong third-party candidate is bad news for the sitting president.

The opposite can also be true

It’s also possible that when third-party candidates do well, it is a symptom of flawed major-party candidates as much as support for the third party.

When Michael Bloomberg considered running as an independent candidate in 2016, he had the money needed to obtain ballot access and the name recognition as the former mayor of New York to appeal to a wide swath of people. But he decided against a run in 2016 in part because he didn’t want to draw support from Hillary Clinton and hand the White House to Donald Trump. We all know how that turned out.

Bloomberg’s late entrance into the 2020 campaign as a Democrat didn’t go very well either.

More effective change agents these days launch campaigns within the parties. Former Rep. Ron Paul of Texas arguably gained more recognition drawing the Republican Party toward his libertarian ideals with presidential runs as a Republican in 2008 and 2012 than as a Libertarian in 1988.

Trump’s tease of a Reform Party run during the 2000 election never went anywhere.

And while he never officially joined the Democratic Party, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont was its progressive champion in 2016 and 2020, although he never won the nomination.

The 2024 third-party landscape

It is through the above lens that third-party efforts should be viewed.

Just about everyone in the middle of American politics can commiserate that the two choices Americans will be offered next November aren’t enough to do justice to a large and thriving republic of 50 states and more than 330 million people.

President Joe Biden, despite dismal approval ratings, does not face serious opposition for the Democratic nomination. And Trump, despite equally dismal national approval and looming prosecutions, is currently in the driver’s seat for the Republican nomination.

That means the most likely scenario, at least for now, is a rematch of the bruising 2020 race, which culminated with the Capitol insurrection after Trump tried to change the results.

The current third-party alternatives would seem to be more damaging to Biden

From the left, the academic Cornell West’s plan to seek the Green Party nomination should be taken seriously by Biden, according to CNN senior political commentator David Axelrod, who said on Twitter it was “risky business” for the Green Party after, he said, they helped tip the election to Trump in 2016.

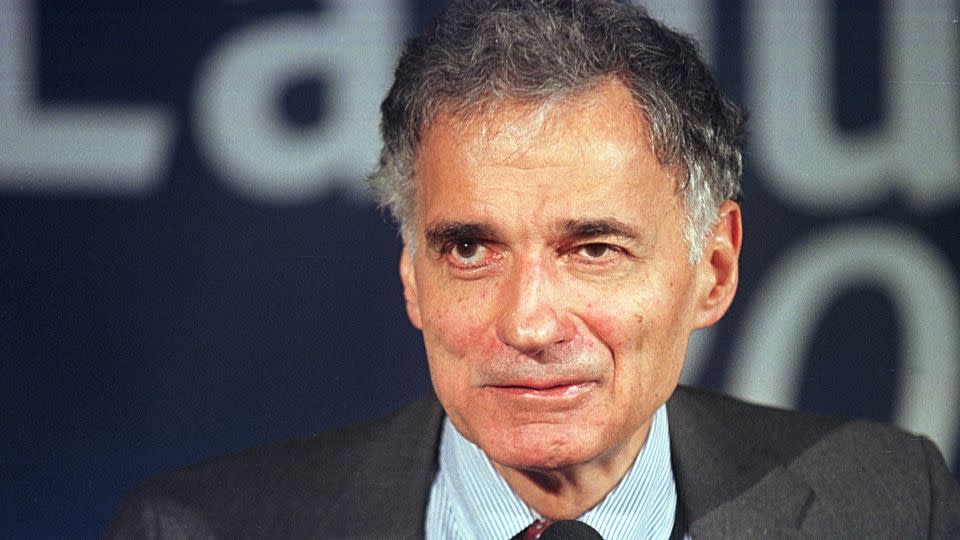

From the middle, the group No Labels outlined a moderate agenda at a town hall in New Hampshire on Monday. Its leader, former Sen. Joe Lieberman of Connecticut, knows how it feels to have a victory spoiled. Many Democrats to this day feel that Ralph Nader’s 2000 Green Party run kept Al Gore out of the White House. Lieberman was Gore’s running mate.

Another moderate group, Third Way, has argued the No Labels unity ticket would hurt Biden more than Trump.

About a third of Republicans compared with 45% of Democrats said in a recent NBC News poll that they would consider a third-party candidate. If the coming election is like previous examples, small margins of voters in certain key states will hold the election in the balance, which means even a small portion of third-party votes could have a big impact.

Gaming the middle

Gore picked Lieberman in part because Lieberman should have appealed to moderates and independents and had been unafraid to criticize Bill Clinton during his impeachment trial.

Lieberman, a foreign policy hawk, veered farther away from Democrats during the war in Iraq. His own presidential run in 2004 barely registered with voters. By 2006, he lost the Democratic primary to keep his Senate seat, but he was able to prevail that November by running as an independent.

That could be evidence that there’s a political middle unrepresented by the parties until you factor in the help Lieberman got in his independent bid from Republicans like Karl Rove, who abandoned their own candidate in favor of Lieberman.

By the pivotal 2008 presidential election, Lieberman had turned against Democrats to oppose then-Sen. Barack Obama and endorse Republican Sen. John McCain.

Now Lieberman’s gaining support from some Trump-opposing Republicans, like former Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan, but drawing the ire of even moderate Democrats.

Appealing to the middle from Washington can be lonely

The main draw for a town hall planned to outline the No Labels middle-of-the-road agenda is Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, who rather than riding a groundswell of support in the middle of the road is fighting off detractors on both sides.

His improbable longevity as a Democratic senator in an otherwise red state has frustrated Republicans by keeping them out of the Senate majority. His committed independent streak is undoubtedly what keeps West Virginians behind him – but it absolutely tortures Democrats, who salivate at what else they could have accomplished during the Biden presidency if he had just bought into the party line.

That positioning makes it hard to imagine Manchin would mount a very successful independent presidential bid, if he’s even seriously considering it.

For all their frustrations with him, most Democrats would probably rather see him run for reelection to the Senate, where he could help them keep a majority in a very tough election year.

The Green Party view

West made clear why he doesn’t think either Biden or Trump is a viable option during an appearance on C-SPAN. Trump, according to West, is “a gangster in the objective sense.”

And of Biden, West said, “I love the brother, but he’s a hypocrite. And he’s pushing toward World War III when you talk about what he has to say about China and Russia.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com