D.G. Martin: Omar ibn Said, who had Fayetteville ties, was enslaved but an Islamic scholar

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

What should we teach young students about slavery and its place in North Carolina history?

Should we follow the example of Florida where new standards for teaching junior high students suggest that slavery’s benefits be included? For instance, a discussion of the jobs enslaved people performed in agricultural work, painting, or blacksmithing should show how “slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

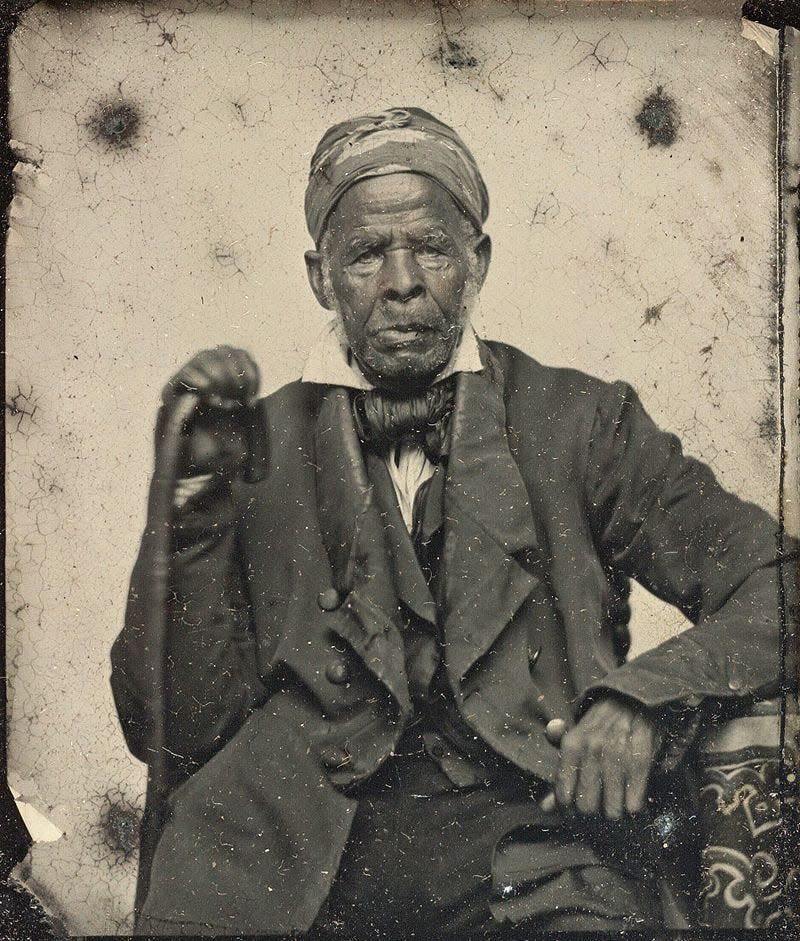

I wonder how the Florida teachers would deal with the story of Omar ibn Said, a scholar of Islam, who was captured and taken from his African home in what is Senegal, brought to the slave market in Charleston, S.C. in 1807, and sold. Ultimately, he was acquired by James Owen, a prominent planter and brother of a governor of North Carolina. Omar lived with his family in Bladen County, Wilmington and Fayetteville, where a historic marker stands at the mosque named for him on Murchison Road.

Omar was fluent in Arabic. He wrote numerous short pieces in Arabic as gifts for the friends of the Owens and a short autobiography.

Omar’s situation caught the attention of people in pre-Civil War North Carolina, and a long article about him was published in the North Carolina University Magazine dated September 1854. It referred to Omar as Uncle Moreau.

More: An opera based on the life of an enslaved former Fayetteville man has won a Pulitzer Prize

More: When few enslaved people in the US could write, one man wrote his memoir in Arabic

Here is a portion of that article.

“At the time of his purchase by Gen. Owen, Moreau was a staunch Mohamedan, and the first year at least kept the fast of Ramadan, with great strictness. Through the kindness of some friends, an English translation of the Koran was procured for him, and read to him, often with portions of the Bible. Gradually he seemed to lose his interest in the Koran, and to show more interest in the sacred Scriptures, until finally he gave up his faith in Mohammed, and became a believer in Jesus Christ. He was baptized by Rev. Dr. Snodgrass, of the Presbyterian Church in Fayetteville, and received into the church. Since that time, he has been transferred to the Presbyterian Church in Wilmington, of which he has long been a consistent and worthy member. There are few Sabbaths in the year in which he is absent from the house of God.”

According to this report, “Moreau has never expressed any wish to return to Africa. Indeed, he has always manifested a great aversion to it when proposed, changing the subject as soon as possible.”

Last summer, Omar’s life was the subject of a Pulitzer Prize winning opera co-composed by Rhiannon Giddens, Greensboro native and formerly lead singer in the popular performing group Carolina Chocolate Drops.

This month, UNC Press published “I Cannot Write My Life: Islam, Arabic, and Slavery in Omar ibn Said's America” by Mbaye Lo, associate professor of the practice of Asian and Middle Eastern studies and international comparative studies at Duke University and Carl W. Ernst, William R. Kenan Jr. Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Lo and Ernst have assembled the available writings by Omar, including his attempt to write his autobiography. They have carefully translated his work from the Arabic into English.

They explain why Omar asserts that “I Cannot Write My Life.” There are several reasons. One is that there is no audience for his Arabic writing. Another reason, according to Lo and Ernst, is that a slave who has been commanded to write by a master cannot write for himself.

Omar is also conscious of his own diminished abilities. He writes, “I cannot write my life, I forget too much about my [tribal] language along with the Arabic language. I read now little grammar and little language. O my brothers, I beg you in the name of God, do not blame me, for my eyes are weak and so is my body.”

Lo and Ernst demonstrate that throughout his life Omar remained attached to the Islam he learned as a child and a young man. He may have attended the Presbyterian Church, but for Omar it was Islam that guided his writing and his life.

D.G. Martin, a retired lawyer, served as UNC-System’s vice president for public affairs and hosted PBS-NC’s North Carolina Bookwatch.

This article originally appeared on The Fayetteville Observer: D.G. Martin: Enslaved but a scholar, Fayetteville figure draws interest