'My dad and I were both diagnosed with breast cancer'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

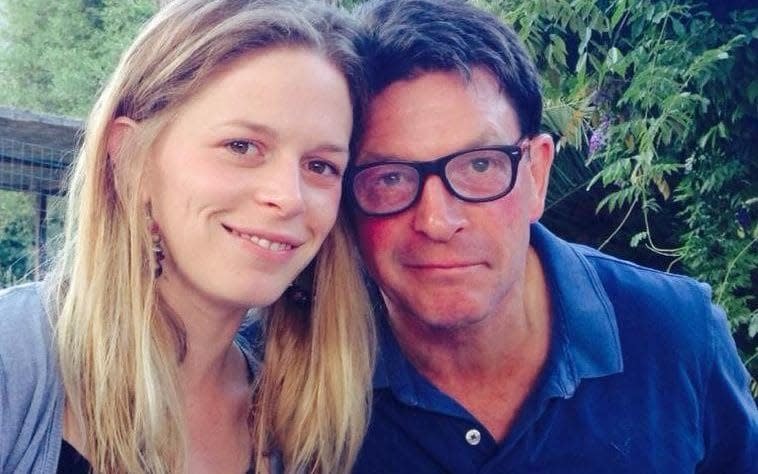

Kate Cockroft, 36, has always had a remarkable amount in common with her father, Mike Greenhalgh. They have a shared love of cycling and hiking, enlivening annual holidays to Devon, where they swam in the bracing waters of the Channel; they are both doctors, and married to doctors.

Since 2014, though, the pair have had one other mutual experience: being diagnosed with breast cancer.

“Suddenly, we became a breast cancer family,” Greenhalgh, 65, tells me over Zoom from his living room in Northamptonshire. Next to him on the screen is his daughter, speaking from Exeter. Seven years ago, when Greenhalgh was 58, he found a lump around his nipple. “To start with, I thought nothing about it,” he remembers. “it seemed to come and go, but then it became more obvious.” Greenhalgh visited his GP, who sent him for a biopsy from a breast surgeon. Within two days, he was diagnosed with bilateral breast cancer, meaning both sides of his chest were affected.

“I was totally devastated. I hadn’t thought that could possibly be the case; I was too young. It was a great shock. As soon as I realised it was advanced I was quite worried about dying. It’s all very well doling out treatment over my 30 years as a doctor, but suddenly you’re on the receiving end, and that puts you in a very difficult position.”

As a GP, Greenhalgh understood that men were perfectly capable of developing breast cancer – but among the general population, the risk is still widely misunderstood. About 400 men are diagnosed with breast cancer each year in the UK, versus 55,000 women, a disparity that means some men wrongly consider breast cancer only a “women’s illness”.

He drove 280 miles to Cornwall to share the news face-to-face with his daughter, who was visiting her grandparents. “I wasn’t expecting Dad to be there; it’s a long way from home,” Cockroft remembers. “I knew then that something was wrong. I was devastated.”

Keen to know if his family were at risk, Greenhalgh arranged a genetic blood test. It came as a further blow when he tested positive for BRCA2 – a faulty gene variant discovered 25 years ago by scientists at London’s Institute of Cancer Research, led by Sir Michael Stratton. We all carry certain genes that protect us from cancer by correcting DNA damage inflicted when cells divide. A BRCA diagnosis means that one of these genes is faulty, allowing DNA damage to go unfixed.

Between 45 and 69 per cent of women who inherit a BRCA2 variant will develop breast cancer at some point in their lives, versus about 13 per cent among the general population. To a lesser degree, a faulty BRCA variant also boosts your risk of ovarian and prostate cancer. Since the publication of Stratton’s findings in Nature in 1996, thousands of women in the UK have been able to detect their cancer earlier, potentially saving lives.

But it also challenges relatives of gene carriers with a tough question: to get tested or not? The NHS says the answer is not clear-cut: some results are inconclusive, it advises, and a positive result can cause “permanent anxiety”.

Indeed, Cockroft felt no rush to get tested. Instead, she focused on helping her father, who was gearing up for a mastectomy, which also removed his lymph glands, followed by six cycles of chemotherapy (lasting for 18 weeks) and five weeks of daily radiotherapy – treatment that left him physically exhausted. “I had other things to focus on,” she says, simply.

Greenhalgh’s treatment so far “seems to have been successful”, though he still has to take a daily dose of Tamoxifen for 10 years. He also raises funds with Walk the Walk, a breast cancer charity.

With the stress of her father’s illness behind her, in 2015 Cockroft finally arranged her own genetic blood test. She knew there was a 50-50 chance of testing positive for the faulty gene (genes come in pairs, one from each parent). Good news arrived when her two brothers both tested negative. But soon after, Cockroft learnt that she was the unlucky one: she, too, carried the BRCA2 gene. She was told she would need an annual MRI scan.

Characteristically calm, Cockroft decided that it wouldn’t affect her life, and planned to have a mastectomy in her early 40s, after she and her husband had children. They thought the matter “would be something I would sort out in a few years. Going on to have two children and deciding to breastfeed them meant she couldn’t undergo MRI scans for 18 months; then, early last year, Cockroft found a lump around her left nipple. She assumed it was a result of breastfeeding, but got it checked out. Her breast cancer diagnosis came a few weeks later.

“I was absolutely devastated, shocked. I think it was in denial that it would be cancer. I had two young kids; I was just getting back to work [from maternity leave],” she recalls.

She received the news in March 2020, when it felt like the “whole world [was] blowing up” because of Covid. The pandemic made her cancer experience dramatically different to her father’s. While he was accompanied to each chemotherapy session by family and friends, she had to walk into hospital alone after being dropped off by her husband. “I sat there for several hours alone, wearing a mask in a very empty department. At that time you weren’t used to people wearing masks; it put the barrier up, you couldn’t see emotions, or reassuring smiles.” Her oncology appointments took place via video. “It was difficult to build a relationship with doctors,” she reflects.

The one person who truly understood her cancer ordeal was her father – but lockdown meant he couldn’t visit. The pair relied on video calls instead, though they remained a paltry substitute in a time of crisis.

Cockroft underwent a double mastectomy in March last year, just hours before Boris Johnson announced the UK’s first national lockdown. She counts herself lucky: while the removal of one breast was medically necessary, the removal of her other was a preventative surgery, and easily might have been cancelled had she had to wait just a few weeks.

Six cycles of chemotherapy and one year later, she is still cancer-free. Her children are four and two; she is starkly aware that each of them has a 50-50 chance of carrying the BRCA2 gene, and will need to decide whether to get tested when they are old enough. “It’s devastating to think of what they’ll have to go through,” Cockroft admits, “but we’ll help them through that.”

Hopefully by that time, she adds, treatment and prevention of cancer may have dramatically improved, sparing a third generation of Greenhalghs the pain their predecessors went through.

You can contact WalkTheWalk here. Male Breast Cancer Awareness Week is 18-24 October. For advice and support with breast cancer, go to Cancer Research UK.