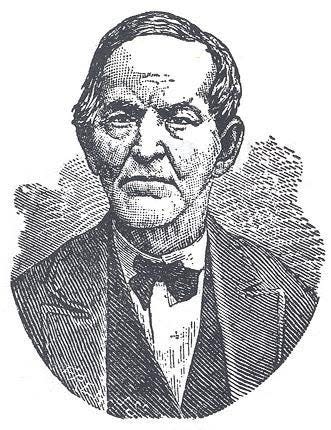

Dan Cherry: The legend of notorious thief Silas 'Old Sile Doty,' with a family connection

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Years ago, as part of a quick research project, I skimmed through the life of Silas Doty, a noted criminal with ties to southern Michigan and Lenawee County.

Doty, known also as "Old Sile Doty," was a "Robin Hood" of sorts, gaining a reputation of staking out more well-to-do residents, taking from them and transporting the item, be it a plow, crops or a horse, to a struggling farmer.

His crimes gave him not only a rush of adrenaline, but also satisfaction that he was able to rob the rich and boost the poor.

Doty was born May 30, 1800, in St. Albans, Vermont. Legend has it he was engaged in a life of thievery and crime from before his teen years, and by the time he died March 12, 1876, in Reading in Hillsdale County, he had built a criminal record that, on paper, would be many feet in length.

What surprised me in recent days is that I found a written account about Doty by my great-great-grandfather, Lester M. Rogers, a longtime Camden newspaper publisher in Hillsdale County and resident of Reading.

In 1943, he told the Detroit Free Press that he was more proud of being a personal friend of Doty's than being a 52-year newspaper publisher. Rogers said that as a young boy of about 4 to 8 years old he knew Doty as a "trusty" from Jackson Prison.

"His home was in Reading; I often sat on his lap and I never knew a kinder man," my ancestor said. "He never stole a horse or a plow to help himself. He only took from the rich to help the poor and he firmly believed he was entirely right in all that he did."

"Doty was widely admired and respected … there are a lot of folks who agreed with him," Rogers said.

My great-great-grandfather was 9 years old when Doty died. I never knew Lester Rogers, as he died Nov. 20, 1963, just two days before the Kennedy assassination and some-nine years before I was born.

As far as I know, that little tidbit connecting my family to Silas Doty was the first and last word on the matter.

Doty had Lenawee County ties as well.

In 1834, he came to Michigan and settled in the Adrian and Tecumseh areas. He set up theft rings near Blissfield and Hudson, stealing fast horses and dispersing surplus crops from rich farmers to the less affluent. He was a former clerk in the Adrian post office, where he used his experience in 1841 to steal mail in New York. From Tecumseh and Adrian, he went to Detroit, before staying again in Tecumseh on his way to Indiana, Mexico and beyond. His life of committing crimes always caught up with him, and regionally he spent many years across several different sentences at Jackson Prison. The longest sentence for his "business transactions," as Doty called them, started in 1851 and ended in October 1866 after 15 years. However, he stole out of retribution the horse of the lawyer who had him sent to prison, and he was returned to his cell. That sentence ended in December 1870. From there, Doty headed north where his continued habits sent him to his old cell again, until he turned 73.

In the three years before Doty died, he transcribed his life of "noble crime" into book form, which was published in 1880 after his death. His book at the time proved to be popular because of its inclination to inspire others to carry on his deeds, but most of the printed copies were tracked down and destroyed by his family. The manuscript found its way to the publishers again in 1948, noting its rarity. Even today, copies of the repackaged 1948 book are difficult to come by.

I have not read Doty's book, but at nearly 300 pages, I can't help wondering if, among his self-aggrandizing moments of thefts and heists, he reflected about the times he entertained a young boy from Reading.

Dan Cherry is a Lenawee County historian.

This article originally appeared on The Daily Telegram: Dan Cherry: Legend of a notorious thief with a family connection