Danger zones: asbestos, toxic chemicals among hazards left at Erie's Quin-T, EMI sites

The block-long vacant property at East 16th and French streets has long been a source of curiosity for Mary Green.

Green, 54, has lived in the 100 block of East 16th street since 1998. Her rented house, owned by the Erie Housing Authority, is among roughly 100 public housing units located within a quarter-mile of the former site of Quin-T-Tech Paper and Boards, which once manufactured asbestos millboard, a cardboard-like product that can be inserted between metal to produce gaskets.

Green lives across the street from the site, where slightly more than $1 million in taxpayer dollars have so far been spent on demolition and environmental cleanup.

For years, Green and her neighbors had no idea that potentially dangerous materials were left inside the dilapidated, unsecured property after it closed — including asbestos and chemicals/substances that have been linked to various cancers.

Urban renewal: Brick by brick, the Quin-T smokestack demo is underway. It will be gone in several weeks

“When I first moved in here, the plant was still operational,” Green said. “The semi trucks were coming in and out all the time and the men over there would wave.

“I really didn’t know what they were doing over there in that building,” Green said. “But I wondered.”

The bustle of industrial activity came to an abrupt halt in 2005, when Quin-T shut down.

The 4-acre former Quin-T complex, at 160 E. 16th Street, was first built in 1890, according to Erie County property records.

After operations ceased, graffiti soon covered the complex’s buildings, which began crumbling without regular maintenance.

Children frequently played at the site, maneuvering around broken glass and other debris.

In one three-year period — 2013 to 2016 — the Erie Bureau of Fire responded to nearly 20 fires at the property that were either accidentally or intentionally set.

Quin-T: Fire-ravaged industrial complex being torn down

"It was one of the most dangerous buildings we’ve ever had to keep going back to," said Erie Fire Chief Joe Walko, a city firefighter for more than 40 years. "We’re lucky no one was ever seriously injured there. It was a heck of a firefighter maze, a monster of a building."

People without homes started to congregate at the Quin-T property regularly, with some sleeping inside and creating makeshift camps that often included bonfires.

Charlie Birittier, 35, was among those with no place to go who often huddled inside the hulking Quin-T complex.

Originally from Louisiana, Birittier is still working to find a permanent home. She stayed at the Quin-T property, on and off, for a few months several years ago.

“I like going and exploring abandoned places,” Birritier said during an interview at the Upper Room, a daytime homeless shelter located on the second floor of St. Paul’s United Church of Christ, 1024 Peach St.

Birritier frequents the Upper Room during the day.

“I’d say every time I went in, there were like four or five other random people," she said. "I used to watch the bats fly around inside there at night, or go to a different floor upstairs and just look at the stars and watch the city light up. It wasn’t scary to me.”

Green said she began to worry about the safety of those like Birritier who spent time at the property.

She also wondered whether the site posed any risks to her neighborhood.

“None of those homeless going inside of there knew what was still inside there, what they produced in there, nothing like that,” Green said. “Neither did we as the neighbors.

“I thought maybe when they shut it down, someone would come to the neighbors and tell us if we needed to worry about the condition of that building or if we needed to wear masks or anything, or what they were going to do about the property eventually,” Green said.

“But nobody came to tell us what was happening. It just sat there.”

The Erie Times-News also told Donna Adams about the hazards left behind for decades at the Quin-T property.

Adams, 80, lives in a Housing Authority-owned home in 200 block of East 18th Street, about two blocks south of the former plant and Green's house. She has lived in that east Erie neighborhood most of her life; the property is frequently on her exercise walking route.

“Knowing that for all these years, people could have possibly been exposed to some of those things that are harmful is disturbing to me,” said Adams, a retired Saint Vincent Hospital employee who is a member of the Housing Authority’s Resident Advisory Board. “If the owners knew there was asbestos and other things there, they should have done something to safely get rid of it all. Especially with blocks full of people living nearby.”

Remembering EMI

Roughly one mile northwest of the Quin–T property, at West 12th and Cherry streets, is the former home of Erie Malleable Iron at 603 W. 12th St.

The complex dates to 1880, and malleable and gray iron castings were once forged there. The property was eventually purchased by Gunite Corp., which decided to close the Erie facility in 2001 and eliminate 220 jobs.

The property, which abuts the homes and businesses of Erie's historic Little Italy neighborhood, has been vacant for more than two decades and is now being demolished. The publicly funded cost of demolition and cleanup at the EMI site stands at roughly $2.2 million thus far.

EMI demolition project: A rumbling, crumbling sight for West 12th Street drivers

Matthew Sidun, 63, created castings as an EMI machine operator from 1993 until the multi-building, 5.4-acre complex was closed in 2001.

EMI's former foundry was torn down in 2009 to make way for the Cathedral Prep Events Center, located across the street from the main complex on West 12th Street, just east of Cherry Street.

“As far as the working environment goes, it was laborious and dirty and tough,” Sidun said.

“You’re working in a foundry in 600- to 700-degree temperatures, with people rotating in and out. But everybody was kind of like family in a way. And overall, I felt safe working there.”

Sidun now lives in Emporium and works for Westinghouse Air Brake Technologies Corp., or Wabtec.

There’s another thing that Sidun vividly remembers about his time at EMI.

“There were a lot of chemicals and oils and stuff there. A lot of things were kept in secure areas,” Sidun said. “We all knew when it closed that there were a lot of (potential) hazards in those buildings, stuff that the company should be responsible for when it comes time to clean it up.”

'This is a national problem'

The Erie County Redevelopment Authority purchased both properties and is leading multimillion-dollar efforts to demolish and clean up both the Quin-T and EMI sites.

The city of Erie has suggested remaking the Quin-T property as a sprawling new public park using American Rescue Plan monies and other funding. The Redevelopment Authority plans to create a new high-tech business park where EMI once stood.

Redevelopment plan: Will $9M in COVID funds turn a crumbling paper plant into a new Erie park?

More: New plans unveiled for Erie's former EMI complex; high-tech business park in the works

But two of the region’s highest-profile brownfield sites had something else in common.

Each property contained tons of debris and/or hazardous materials left behind by their former owners, materials that environmental remediation specialists had to assess and carefully remove before demolition could start.

Many of the potentially harmful materials, according to documents obtained by the Erie Times-News, as well as interviews with those involved in revamping the properties, were used in manufacturing processes at the plants.

Those materials included asbestos; various acids; foams; oils; coal ash; and polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, highly carcinogenic chemical compounds commonly used in industrial and consumer products before their production was banned in the United States in 1979.

A look inside: After 100 years, Erie Malleable Iron plant faces demolition

The potential hazards posed by asbestos are well known.

Long-term exposure to asbestos can lead to a wide variety of cancers; most common are lung cancer and mesothelioma, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Asbestos exposure has also been proved to cause kidney, throat, ovarian and other cancers, the CDC has reported.

“Although asbestos is no longer used in many products,” the CDC reports on its website, “it will remain a public health concern well into the 21st century.”

According to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, a federal public health agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, people exposed to large amounts of PCBs ― which are odorless and have no smell or taste ― can develop skin conditions such as acne and rashes; show changes in blood and urine that could indicate liver damage; and suffer irritation to the lungs and nose.

Justin Burick, an environmental project manager, was hired by the county Redevelopment Authority to work on the cleanup of both the EMI and Quin-T properties.

“The amount of drums and totes and just general debris at EMI, for example, was significant,” Burick said.

“Most of the stuff that went out of EMI was non-hazardous material. But there were PCBs and some hazardous waste there,” Burick said. “And there were paints, used oils, petroleum products. … Just a lot of garbage and other stuff.

“Quin-T, it was riddled with asbestos,” Burick said. “There were pallets of asbestos left there, abandoned and rotting in the basement. That was a real concern.”

County Redevelopment Authority officials provided even more context about the Quin-T building’s condition and the cleanup challenges there, particularly regarding asbestos, in a December 2021 memorandum that updated Erie City Council on remediation and demolition plans.

City Council signed off, in February 2022, on using more than $2 million in American Rescue Plan funds for demolition and related costs at the Quin-T and EMI sites.

Erie City Council: Funding OK'd for Quin-T, EMI demolition

“A multitude of factors complicated the Quin-T asbestos remediation,” the memo states. “All four floors tested positive for asbestos in multiple locations. The entire roof tested positive for asbestos. Window glazing tested positive, resulting in the removal of all windows.”

Further, “much of the basement and first floor contained asbestos adhered to concrete surfaces,” according to the memorandum, “requiring jackhammering to remove (it).”

Tina Mengine, the county Redevelopment Authority’s executive director, said the situation at both the Quin-T and EMI sites underscores why public agencies and taxpayer money are often required to clean up former industrial properties across the country.

Corporations that abandon such sites, Mengine said, are often struggling financially, so they are unable or unwilling to spend millions of dollars on environmental remediation and clearing out the properties.

“The cost of (cleanup) is so astronomical,” Mengine said. “This is a national problem, particularly in the Midwest and the Northeast.

“Our focus is not on blame,” Mengine said. ”It’s on cleaning up these sites and putting them back into productive use. That’s why we exist, and that’s why federal and state remediation programs that provide this kind of funding exist.”

Gunite officials reported at the time of the EMI plant’s closure in 2001 that the company’s revenues were declining and the plant was being shuttered “to realign our capacity with market demand.”

At that time, the Erie plant was melting scrap steel and turning it into components for wheels for heavy-duty trucks as well as wheels for GE Transportation Systems.

According to EPA documents, Quin-T officials said the company lost $277,760 in 2002 and indicated the company was headed for bankruptcy. The East 16th Street plant shut down three years later.

An entity named 140 E. 16th St. Inc., of Depew, New York, sold the Quin-T property to the Redevelopment Authority in 2021 for $10,000, county property records show.

The Redevelopment Authority "temporarily transferred ownership in June" to the city of Erie's Land Bank to qualify for a federal environmental cleanup grant. Mengine said the property's ownership will revert back to the county Redevelopment Authority within the next several weeks.

Representatives of 140 E. 16th St. Inc. could not be reached for comment.

Longtime Erie employer Modern Industries bought the EMI property from Gunite in 2007 for potential expansion. Modern Industries used a portion of the property as warehouse space and light manufacturing for years before selling the property to the Redevelopment Authority for $375,000 in April 2021, according to county property records.

Dennis Sweny, Modern Industries’ co-president, declined comment.

The county Redevelopment Authority purchased both properties as-is, Mengine said, which means the authority is unlikely to recoup any demolition or remediation expenses from the former owners.

The toxins and chemicals left behind

According to Redevelopment Authority records/documents, toxins and chemicals identified at or removed from the Quin-T site included

asbestos, including pallets of asbestos left rotting and abandoned in the building’s basement;

non-toxic styrene-butadiene polymers that can nonetheless cause irritation to the skin and mucous membranes after prolonged exposure;

water-based acrylic emulsions/polymers often used in paint, which can cause headaches, nausea and irritation of the nose, throat and/or lungs, as well as skin/eye irritation. One of those emulsions found at the site also contains formaldehyde, a carcinogen linked to leukemia and various other cancers;

a non-toxic rosin used in various types of paper-related manufacturing;

coagulants that can cause severe skin and eye irritation, vomiting, nausea and diarrhea with prolonged contact;

a defoamer used in the manufacture and application of paints, adhesives, coatings and printing inks. The substance can create toxic gases if ignited;

solidified paint; and

dozens of tires and general trash.

The exact volume of materials was not specified. But according to Redevelopment Authority documents, the cleanup work required at least two six-person crew members on site at all times, plus two excavators and the double-bagging of disposed materials, which filled 20 lined construction dumpsters.

Historical manufacturing operations have the potential to impact soil and groundwater at the site, according to authority documents, and have been identified as what's known as a "Recognized Environmental Condition Phase 2," which means the threat of pollution exists at the property.

Preliminary soil and water testing near the Quin-T site indicates that additional cleanup and study of potential environmental impacts will be necessary, according to Redevelopment Authority documents.

According to an initial environmental assessment by AMO Environmental Decisions of Doylestown, "historical manufacturing operations have the potential to impact soil and groundwater" at the Quin-T site.

AMO is an environmental resource management consulting company that worked on the EMI and Quin-T cleanups.

Further, "the basement (at Quin-T) reportedly may contain trenches, sumps, and pits, though the basement of the former building could not be accessed during the site reconnaissance," AMO's report states. "The inability to access the basement adjacent to the existing building represents a significant data gap."

Work crews also removed two 30,000-gallon underground tanks from the Quin-T site.

The EMI cleanup, according to Redevelopment Authority documents, involved

disposing of 800 drums and 240 containers of waste, including various oils, acetone (a flammable, toxic industrial solvent) and PCBs. James Bedison, a project manager and environmental specialist at AMO Environmental Decisions of Doylestown, said the PCBs and chemicals contained in some of those drums “represented a major environmental issue and (were) in no way being properly managed” when cleanup crews discovered them;

removing 3,000 pounds of various liquids and sludge;

removal of six old oil tanks of various sizes;

removing a significant amount of coal ash ― produced when coal is burned to provide power within industrial plants ― throughout the complex. Coal ash, according to both the CDC and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, can irritate the skin, eyes, nose and throat; cause respiratory problems; and with long-term exposure could even lead to some types of cancer; and

disposing of 400 wooden crates and more than 60 tons of other potentially contaminated debris including paper, desks, chairs, file cabinets and other abandoned office equipment.

As demolition continues, another 100 tons of debris will likely need to be disposed of, according to county Redevelopment Authority officials.

Further, extensive asbestos testing at EMI, before demolition began, revealed “74 suspect asbestos-containing material samples were collected from twenty seven (27) homogenous areas” within the plant, according to a report from Pittsburgh-based Cosmos Technologies, an engineering consulting firm that handled asbestos surveying at EMI.

The company found asbestos throughout the property, according to its report, including within roofing, ceiling coatings, pipe insulation, flange gaskets, ceiling panels, water tank insulation, floor tile and joint compounds.

Cosmos Technologies’ report suggests that even more asbestos was likely present at the abandoned plant. The company's report also noted that "nearly all of the second-floor ceiling has collapsed and about 20% of the first-floor ceiling was caved in and inaccessible."

The report further states: “the inspector made every effort to locate all asbestos containing materials identified during the limited inspection. ... However, inaccessible materials hidden behind solid barriers such as plaster/concrete walls and ceilings are not addressed in this report.”

A preliminary environmental report on the EMI site conducted by AMO also recommends "additional appropriate investigation" of potential environmental hazards, such as soil/groundwater testing, "to further evaluate potential environmental impacts in accordance with applicable state and federal regulations."

'Environmental justice'

Jenny Tompkins is a campaign manager for clean water advocacy at PennFuture, a statewide environmental organization with offices across Pennsylvania. She is also a member of the city of Erie's Environmental Advisory Council, a volunteer group that works with city officials on various environmental issues.

More: Erie's new Environmental Advisory Council eyes sustainability, equity

Tompkins said the abandonment of the Quin-T and EMI sites is problematic on a number of fronts as local officials assess whether the materials left behind have a lasting environmental impact.

Tompkins said the issue is one of environmental justice — the social movement to address concerns about the potential exposure of poor and marginalized communities to harm from hazardous waste, resource extraction and other environmental issues.

Both the Quin-T and EMI sites are located in state-designated Environmental Justice areas, defined by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection as any census tract where 20% or more of the residents live at or below the federal poverty line or where 30% of the population identifies as a non-white minority.

In the census tract that includes the Quin-T property, 51% of residents live below the federal poverty level, according to U.S. Census Bureau data, which is more than three times greater than the overall Erie County poverty rate of 16%.

Nearly 60% of those who live there identify as non-white.

Census data shows that 43% of residents living in the census tract where the EMI site is located live below the federal poverty level and more than 40% of residents in that area identify as non-white.

"There is a lot at stake for communities like Erie contending with legacy and emergent industrial pollution," Tompkins said. "Industrial pollution places a tremendous financial burden on taxpayers and threatens human health, particularly for communities of color and those in poverty that are already disproportionately burdened by pollution.

"Contaminants can run off into local waterways, threatening drinking water quality and making their way through our ecosystems and food chains, leading to fish consumption advisories like we see in Presque Isle Bay and Lake Erie," Tompkins said. "Vacant and abandoned properties are linked to higher crime rates and declining property values, creating barriers for future investment."

Tompkins added: "Unfortunately, in many cases, local communities like Erie must foot the bill for abandoned industrial and commercial property because of a lack of laws and regulations holding companies accountable."

Potential risks

Bedison, of AMO Environmental Decisions, helped the county Redevelopment Authority adhere to federal and state environmental guidelines related to the Quin-T and EMI cleanups.

He also was key in helping the authority secure a $526,000 environmental remediation grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The company has consulted on similar projects nationwide. Bedison said the Quin-T and EMI properties each housed potential hazards.

At Quin-T, Bedison said, “the basement had asbestos, old chemical drums filled with emulsifying agents and other things, and a whole network of old trenches and old sumps that were all full of water.”

“There’s a reason why use and storage of chemicals is regulated by a lot of different government agencies,” Bedison said. “If they’re left to just sit there and leak over time, that’s a problem, especially when they’re stored in an unsecured, abandoned building.”

Inside the EMI property, Bedison recalled, cleanup crews found “floor-to-ceiling piles of garbage and pallets and piles of who knows what” on the west side of the complex’s main building.

“A lot of old laboratory equipment and some laboratory chemicals were kind of heaped up in there,” Bedison said. “The roof was leaking badly. And lots of old 250-gallon waste containers that weren’t disposed of properly. There were hundreds of them.

“Absolutely,” Bedison said, “there’s a potential environmental risk there.”

Do you have a story to tell about either the Quin-T or EMI properties?

Did you work at/live near either plant, or do you know someone who did? Do you have health-related concerns that you believe might be linked to one or both of those sites?

The Erie Times-News wants to hear from you. Contact reporter Kevin Flowers at kflowers@timesnews.com or 814-881-1582.

'Polluting our neighborhoods'

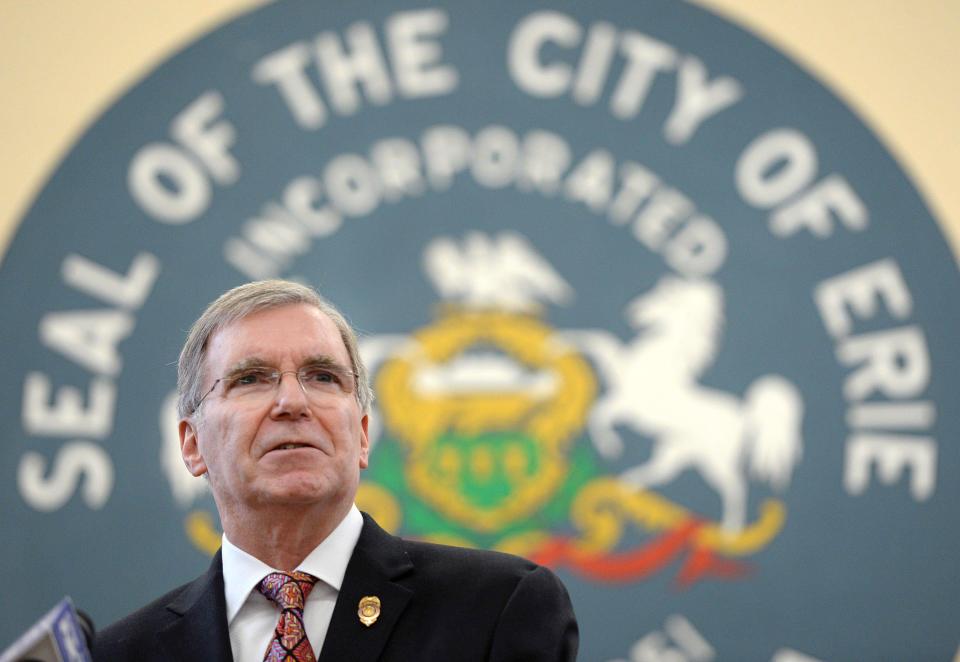

Erie Mayor Joe Schember applauded the county Redevelopment Authority for taking the lead on the Quin-T and EMI redevelopment projects.

However, Schember said, the fact “residents have had to live next to this industrial blight is unacceptable. It’s a travesty that these companies went out of business and left behind literally tons of asbestos at Quin-T and more than 800 drums of hazardous waste from EMI, not to mention sludge, oil tanks, and coal ash.

“The private sector would never undertake projects like Quin-T or EMI because of all the time and effort and funding involved in the clean-up alone,” Schember said. “That’s why these properties sat vacant and abandoned for decades, polluting our neighborhoods within the urban core.”

Mike Fraley is the Erie Housing Authority’s executive director. The agency owns and manages more than 2,000 housing units citywide for low- and moderate-income families, older residents and people with disabilities.

Fraley said that number includes roughly 130 units in the area near the Quin-T site, including the houses Mary Green and Donna Adams occupy near the property.

“We’re happy for everything the Redevelopment Authority has done over there cleaning it up,” Fraley said. “But it’s not visually attractive, and it could be dangerous for the people who live near there, including our residents.

“These companies who abandon these places should be stewards of the community. But it doesn’t look like there's a lot of consequences when they aren’t,” Fraley said. “They just get up and walk away from these buildings, and that’s not right.

“Unfortunately, you see this all over the United States,” Fraley said, “and especially in the lower-income areas.”

Bedison, the AMO Environmental Decisions project manager and environmental specialist, said he believes the buildings' former owners should have felt "some responsibility to the community to leave these sites in a relatively clean states, where they don't represent potential environmental or human health hazards.

"The cost is a major factor here," Bedison said. "We know that whoever is leaving these sites abandoned doesn't necessarily want to pay what it would cost to leave it in a state where it's not burdensome to the community. They often don't want to deal with the money or the time to do it right. And these are not fast processes to go through."

Coming up in the Erie Times-News:

State and federal environmental officials raised concerns about the Quin-T property and its toxic contents for years; Erie firefighters responded to multiple blazes at the abandoned complex, which was often frequented by homeless men and women.

The EMI property was rapidly deteriorating for decades along the West 12th Street industrial corridor while potentially harmful chemicals and toxins sat inside, unsecured.

Contact Kevin Flowers at kflowers@timesnews.com. Follow him on Twitter at @ETNflowers.

This article originally appeared on Erie Times-News: 'Industrial pollution': What was left behind at Erie's Quin-T, EMI properties