Dangerous ‘extreme heat’ days to multiply in South Florida, study finds. Who is at risk?

Yes, it’s already very hot in Miami-Dade County. But if climate change continues unabated, South Florida could go from steamy to scorching, adding an extra month of “extreme heat” days by mid-century.

That kind of extreme heat makes it hard to work — or live — outside and can sicken or even kill people, particularly outdoor laborers, the poor and the elderly. That’s a problem for Miami-Dade, which has more than 100,000 outdoor workers, the most in the state. It also will make cooling homes, buildings and cars pricier.

A report released Monday from the nonprofit climate research group First Street Foundation found that Miami-Dade leads the nation as the county that could see the sharpest increase in dangerous hot days over the next 30 years, when the U.S. could be an average of 3 degrees hotter.

The Southeast, including Florida, is likely to see much higher temperatures more frequently. That means extra weeks of the year where temperatures top 100 — or even higher.

“It’s getting warmer there, and while it’s easy to say ’it’s already hot here,’ the exposure to more dangerous days is what dominated the story in our report,” said Jeremy Porter, First Street’s chief research officer.

The First Street report found that South Florida, including Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach counties, could see about 40 extra days a year where the heat index is over 100 degrees Fahrenheit. The region gets about 50 a year now. Heat index — also known as the “feels like” temperature — factors in humidity with temperature.

These findings mirror previous studies’ projections of what global warming could feel like for South Florida, a warning that pushed Miami-Dade to hire its first Chief Heat Officer, set up an extreme heat task force and conduct a heat vulnerability study.

“It reinforces what we’re already planning for,” said Jane Gilbert, the county’s chief heat officer. “The quality of life in Miami-Dade County in 30 years is highly dependent on how globally we’re able to control greenhouse gas emissions. It’s imperative that as a county and a state we are leaders on greenhouse gas emissions reductions.”

Who’s at risk?

That vulnerability report, published earlier this summer, is already guiding investments.

Researchers found that Miami-Dade has an average of 58 hospitalizations and 301 emergency department visits a year for heat-related illnesses. Deaths are harder to count. In the five-year span, only two death certificates listed extreme heat as the first cause of death.

Christopher Uejio, an associate professor at Florida State University and lead author of the analysis, said that’s both because medical examiners have a high bar for counting heat as the main cause of death and because “heat exacerbates such a long list of health conditions that it’s hard to tease it out.”

In the analysis, researchers found that changing that standard to include all illnesses that extreme heat would have worsened brought the total to 34 deaths a year.

As the county warms, those deaths increased. Every 10-degree increase in the heat index led to an additional death a day, the study found.

“Without further adaptation, we could expect heat-related illnesses and deaths to increase,” Uejio said.

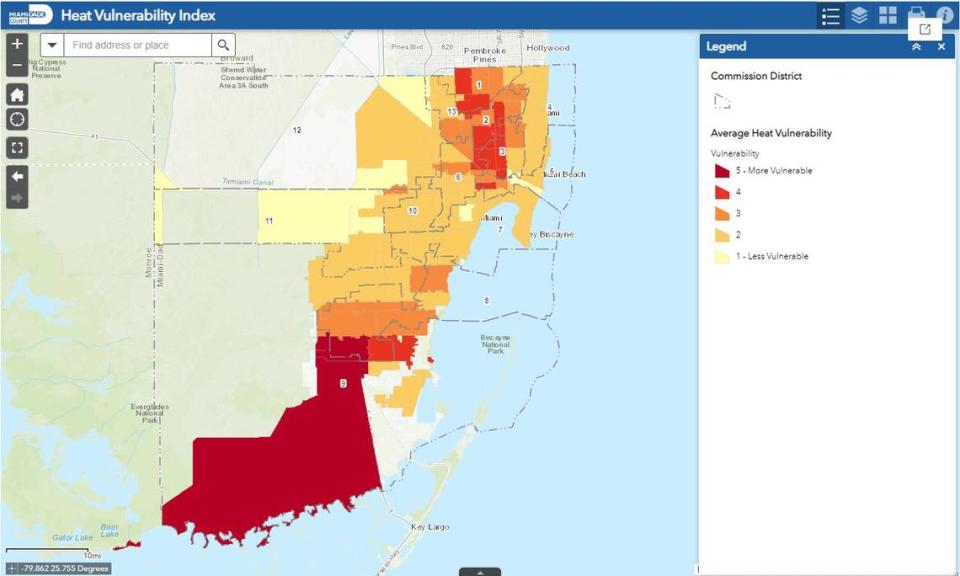

From there, researchers took the risk factors for heat-related illness and death — like poverty, whether people work outside or live in mobile homes or if they have children — and mapped it out across the county.

The ZIP codes with the highest risk were in South Dade, Miami Gardens and the Allapattah area.

Gilbert, the county’s heat czar, said she’s targeting these areas for tree planting and preservation to keep them cool, and they’re first in line for the 360 new shaded bus shelters the county is installing this summer.

They’re also the focus of the county’s heat season campaign of public service announcements, billboards and presentations.

“We used the vulnerability assessment to focus our investments in boosting the videos and social media posts and bus shelter ads in ZIP codes with the highest rate of heat-related hospitalizations,” Gilbert said. “We’ve reached over a million residents already in our campaign and we’re continuing at it.”

Living and working in the heat

While researchers looked at a long list of factors that increase someone’s risk of experiencing extreme heat, it boils down to two things: spending a lot of time outside, usually while working, or living somewhere that isn’t properly cooled.

Miami-Dade has more outdoor workers than anywhere in the state, but there are no laws at the state, national or local levels to protect them from heat stress.

The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration has been slowly turning its set of recommendations about offering laborers water, rest and shade into laws, a multi-year process. In Florida, a bill that only recommended employers consider offering some protections against heat stress (with no penalties for not doing so) died after a single committee hearing, where it won unanimous, bipartisan approval.

Miami-Dade is looking into proposing its own policy, Gilbert said.

“We’re going to get the strongest possible policy that we can pass and hold. We have to hope it won’t get preempted,” she said.

The other side of the equation is housing. Most apartments, condos and homes in South Florida include air-conditioning units, although it’s not standard in federally subsidized housing. But running the AC is expensive, and as the cost of energy rises, cash-strapped households often cut down on cooling to lower their bills.

One solution from the county is cooling centers or heat shelters. These are public spots, usually community centers, parks and libraries, where residents can come chill out during the hottest points of the day.

Ladd Keith, a University of Arizona assistant professor of planning and sustainable built environments, said that these are helpful, but they don’t get at the real problem of overheated housing.

“If the temperatures are still elevated in the evening, you’re essentially sending those individuals back to unsafe conditions,” he said. “The root cause is we need everyone to have a safe home to live in. The reason we need cooling centers in the first place is we need everybody to have a safe place to live.”

Introducing: heat season

If there is good news for Florida, heat waves and extreme temperatures aren’t as common as they are in the western U.S. because of the cooling effects of the nearby Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico.

“There’s almost a ceiling, a physical limit to how hot it can get because of the water,” Porter said. “But there are a few places in Florida and along the Atlantic coast where that protective effect is starting to diminish because sea surface temperatures are increasing.”

Florida’s brand of heat risk can be more difficult to warn people about. It’s easier to sound the alarm for a three-week heat wave or a two-day temperature spike than simply saying the whole summer will be sweltering.

Eyeing the potential health impacts of heat, Miami-Dade started announcing an official heat season, which runs from May through October. It’s one more way to warn residents about the kind of risk they face, since the threshold for a warning from the National Weather Service is so high — a heat index of 108 degrees.

That doesn’t happen often. By the calculations in the First Street report, Miami-Dade hit that figure zero times this year, and after another 30 years of warming, it’s projected to hit that number just three times a year.

To solve that, Gilbert and the county worked with the local NWS office to come up with lower thresholds to warn residents about heat risk. At a heat index of 103, the NWS now talks about taking “extreme caution” in the heat in its forecasts.

“I think the NWS has always wanted to be mindful of not having to issue a heat advisory or heat warning too often because people might disregard it,” she said. “It currently shows that we have room to issue these kinds of advisories and still get people’s attention.”