The Dangerous Side Effect of Digital Wellness

The direct-to-consumer health and telemedicine industry is booming — but the way some medications are marketed online is creating controversy.

Do you get butterflies before a first date? Sweaty palms? Maybe you let out a nervous giggle or two? Well, direct-to-consumer digital healthcare platform Hers is here to save the day. The woman-centric wellness brand makes getting your hands on prescription Propranolol, a cardiovascular medication that has the serendipitous side effect of masking symptoms of anxiety, easier than ever — just add to cart and fill out a questionnaire, and you, too, can find sweet relief from basic human nature.

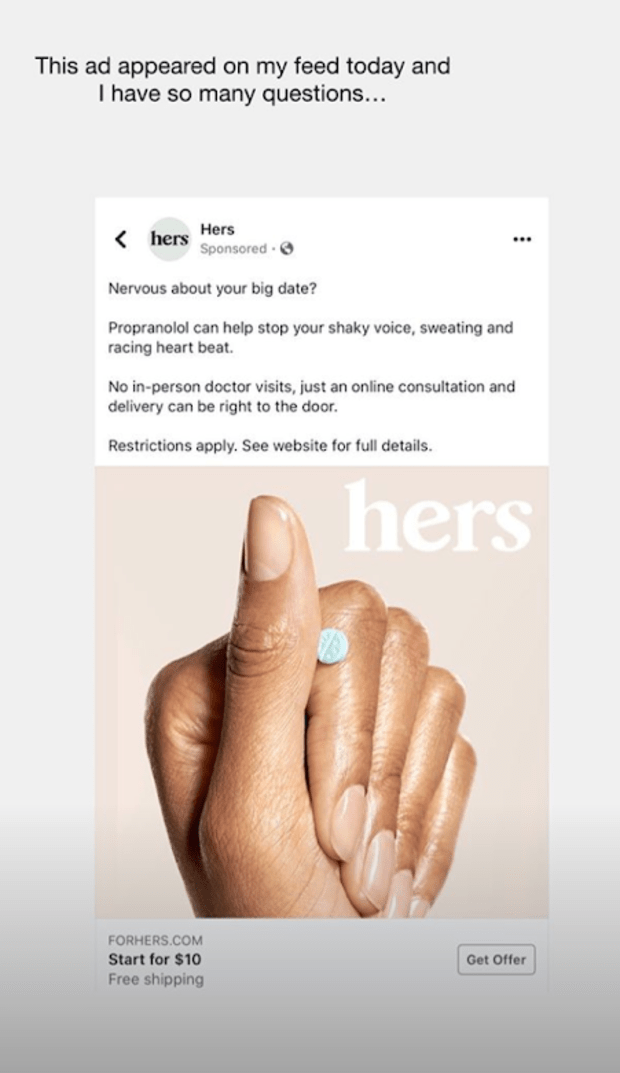

Okay, that's not actually the mission of Hers… even if its now-infamous, Propranolol-pushing Facebook ad, published earlier this month, indicated otherwise.

"Nervous about your big date?" it read. "Propranolol can help stop your shaky voice, sweating and racing heart beat." It went on to highlight that no in-person doctor's appointment was necessary to obtain a prescription, with nary a mention of the medication's potential side effects (which include depression, insomnia and low blood sugar, among others).

Clicking over to forhers.com reveals a site clearly designed with millennials in mind — the Glossier of healthcare. Diverse, "makeup-free" models smile while applying moisturizer to the apples of their cheeks. Manicured hands hold prettily-packaged products against poppy, pastel backgrounds. But it's not cleanser or concealer on display here. It's a host of prescription medications, from anxiety-reducing Propranolol to acne-clearing tretinoin to birth control pills in shiny, holographic packets.

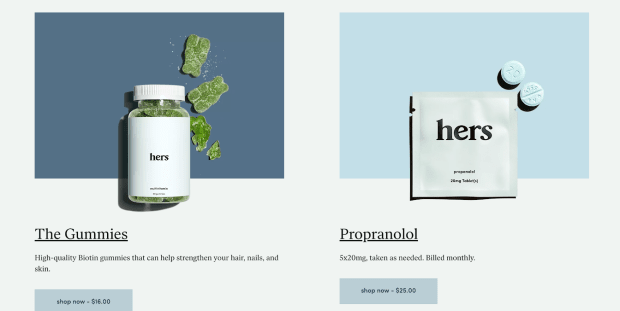

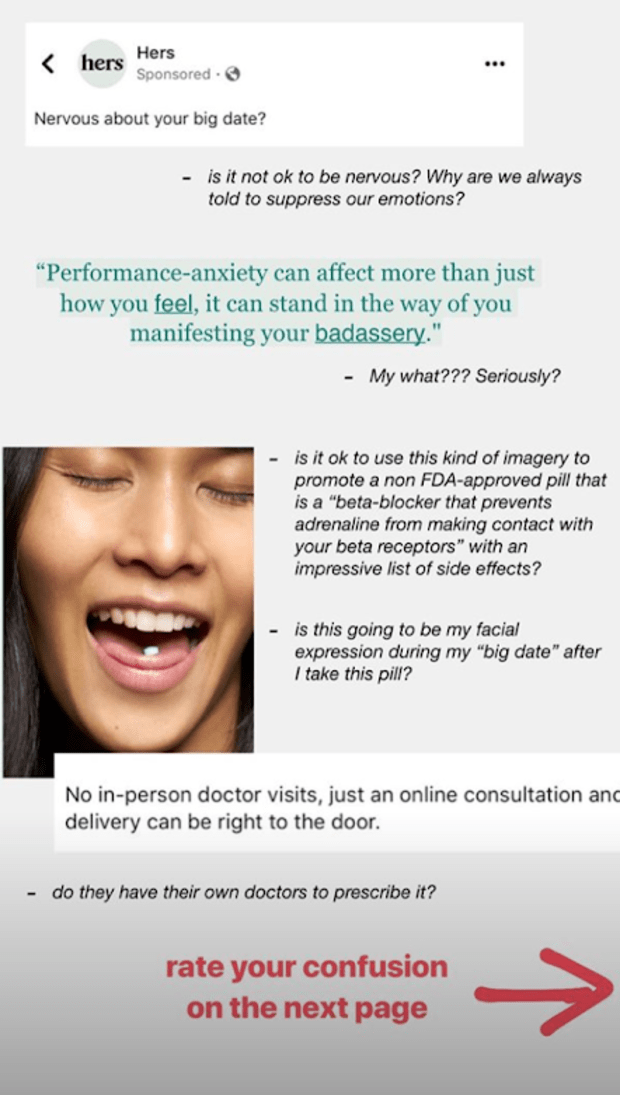

To buy Propranolol, customers can click the handy "shop" link in the top nav, then scroll past the Skin, Sex and Hair categories to land on Well-Being. "Calm doesn't always come easy, and an apple-a-day doesn't always keep the docs away," the page's headline reads. Two products are featured below: sugar-coated, neon-green gummy bear vitamins… and the aforementioned prescription anxiety pills. Finally, a foot-long list of side effects appears on the Propranolol product page — just above imagery of a model popping a baby-blue pill, eyes closed and mouth agape in ecstasy.

The too-casual, somewhat reductive, highly-stylized journey from ad to cart caught the attention of influencer Yana Shept of @gelcream, who broadcasted screenshots — along with her candid distaste — to her 109k Instagram followers. The story was then picked up by @esteelaundry, an anonymous online collective known for calling out sketchy behavior in the beauty industry; and the rest, as they say, is history. The kind of history that lives on ad infinitum in Story Highlights.

"I saw it on Facebook and it immediately made me upset," Shept, who has suffered from anxiety herself, tells Fashionista. "I was shocked by both the language and the ecstatic face of a model taking the pill. This is not a sweet pill; this is not the right way to market drugs." She points to the fact that Propranolol is actually a beta-blocker intended to treat high blood pressure, its only FDA-approved use. However, some doctors, like the partners employed by Hers, prescribe it for off-label treatment of anxiety.

Shept's audience was similarly alarmed — her Stories post elicited a response from nearly 10,000 people. "There is a huge difference between clinical anxiety and nerves," one messaged. "As someone who takes propranolol for anxiety, I can't believe this is a thing. Feeling nervous about a date is completely normal. I feel like this complete invalidates the fact I have been prescribed this medication for generalized anxiety," said another.

"For those who were unhappy, we understand why, and agree the post was misguided," Hilary Coles, the brand lead of Hers, tells Fashionista. The company issued an official apology on its social channels not long after Shept's call-out, stating "We got this one totally wrong" and adding that it had "slipped through the cracks."

But for Shept, it was too little, too late. "I think they missed the point and it was not really an apology," she says; it was a sentiment echoed by others who found the original Hers ad offensive. "[It was] rather another nicely designed and copywritten Instagram post. I expected to see the face of a founder taking responsibility."

While it remains to be seen if and how the backlash will impact Hers (the company has taken down that particular ad but is still promoting Propranolol sans side effect warnings in paid ads on Instagram and Facebook), the event shines light on a larger issue: Responsible marketing of telemedicine in the Instagram age.

Hers is just one of the many telemedicine platforms — aka, digital healthcare sites that treat patients via online questionnaire, video chat or phone call, rather than in-person — to pop up in the past handful of years. There's also its brother site, Hims; as well as Maven Clinic (a family-oriented virtual care center), Cove (targeted at migraine sufferers), Keeps (a men's wellness platform) and Skin Laundry Rx (a digital dermatologist's office currently in beta testing), to name a few. Seven million Americans reportedly accessed care through telemedicine platforms in 2017 alone, and that number is only going to grow.

"There is an argument that telehealth can assist with access for remote patients and socio-economically marginalized groups," Daniel O’Connell, LCSW, who specializes in mental health and addiction, tells Fashionista. "That is a strong case, and with merit." Telemedicine helps level the playing field, so to speak, for those with disabilities or immobility.

Insurance (or lack thereof) is another major factor. "According to a recent Statista dossier on women's health in the U.S., a quarter of women do not have health insurance, due to cost and healthcare inequalities, among other reasons," Coles says. "At Hers, we are dedicated to providing affordable and convenient access to healthcare for everyone, including those without insurance options." Hims, Cove and Keeps work in much the same way, side-stepping traditional insurance providers in favor of flat consultation fees. "Our prices are often less than the cost of what patients would pay at their local pharmacy," says Steve Gutentag, the co-founder of Thirty Madison, the parent company of both Cove and Keeps.

Then, of course, there's the issue of time. Patients are increasingly over-scheduled and can't spare the hours it takes to research an in-network provider, make an appointment, take the afternoon off to attend said appointment and waste time in the sure-to-be-crowded waiting room. "We've found women are more inclined to provide full details of their symptoms via telemedicine versus going into a doctor's office," adds Coles.

But for all its merits (of which there are many! Yay for accessible, affordable birth control!) telemedicine is not without its risks — especially when it comes to mental health.

"I have worked for years with a very specialized psychiatrist who I trust, and we have had multiple patients coming from other services with the incorrect medication," says O'Connell. "The wrong medication can keep a patient cycling in and out of periods of poor mental health, it can even trigger an episode or worse — it can increase suicidal thoughts." Considering the fact that many telemedicine platforms provide mental health meds — Hers with Propranolol, Cove with antidepressants and beta-blockers (both of which have been shown to help with migraines) — based on little more than a digital questionnaire at least and a follow-up call or online chat with a doctor at most, this is a legitimate point of worry.

"A key concern with telemedicine is that you lose the opportunity for additional assessment — for instance, if a patient is coming to see their doctor they must also interact with a receptionist, perhaps a nurse or a care-worker," O'Connell shares. "How a patient behaves prior to meeting with the doctor can be very informative. If the patient is pacing around the waiting room, crying or talking to themselves or distracted by internal stimuli, the other staff will witness that." He adds that it's typically best practice to pair mental health medication with ongoing talk therapy (which can get lost in a telemedicine setting), and warns that those who self-identify as anxious may actually be in the throes of something more serious, like "schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder or brief psychotic disorder."

While it's true that obtaining a prescription for medication in-person can also be a relatively simple process — O'Connell states that antidepressants and anti-anxiety pills can be prescribed by regular primary care physicians, with no specialist input — telemedicine simplifies it further. With Hers, for example, customers decide what medication they want, add it to their cart and pay via credit card… all before a medical history is taken or a professional consultation enters the picture. "This setup is designed to ensure a seamless experience for customers as they go through the flow of the online medical consultation and purchase process," Coles explains of the purchase-driven UX. If the medication is determined to not be a good fit for the customer after checkout, a refund is issued. Cove has a similar process in place.

When pressed on what percentage of patients are denied the antidepressants, beta-blockers, or other migraine-focused medications they hoped to receive through Cove, Gutentag says the tele-platform doesn't track that data "because the consultation isn't about approving a prescription." Many of Cove's customers forgo medication, yet continue to consult with a tele-doctor to control their condition.

Consumers have shown a bit of skepticism around obtaining mental health meds online — as evidenced by the Hers backlash — but most are more accepting when it comes to skin-care prescriptions. Skin Laundry Rx, a prescription-focused, online extension of the Skin Laundry brand, is currently in beta testing throughout California (with plans to extend to 22 states) to provide patients with "prescription skin-care medications formulated and customized by our team of medical professionals to match each individual's unique concerns and sensitivities," Elyse Shelger, the brand's director of medical operations, previously told Fashionista. Hers similarly offers three prescription-strength skin creams: anti-aging retinol, tretinoin for acne, and a steroid-spiked treatment for melasma.

But just because the seamless online purchasing process feels akin to placing an order on Sephora, it doesn't mean these high-strength skin prescriptions don't sometimes have noteworthy side-effects, too. "Telemedicine definitely fills a need in underserved areas, where patients may not have direct access to board-certified dermatologists," says Dr. Joshua Zeichner of Zeichner Dermatology in New York City. "However, it does not take the place of visiting a dermatologist in person."

Why not? Because many important indicators are not visible in photos or via video chat, and some skin conditions can even point to deeper health issues (most often hormonal imbalance), which may go unnoticed via an online quiz. And for those with sensitive or reactive skin, prescription-strength topicals can actually make things worse — retinol, for example, can compromise the skin's barrier.

These factors are just part of what makes the battle cry of the Hers beauty section so disturbing: "If it's not prescription skin care, how do you know you're not just applying marketing?" the site asks.

Oof. Where to start? First of all, the pharmaceutical industry spent a staggering $30 billion on marketing in 2016, up from $17.7 billion in 1997; an estimated $6 billion of which was used to directly target consumers, according to a 2019 study from Dartmouth College. So, you're in fact very likely to be "applying marketing" with a prescription. Secondly, medical marketing has always been murky territory — the Federal Drug Administration and the Federal Trade Commission have vague guidelines that, historically, have been weakly enforced at best — and telemedicine only adds to that murkiness.

"Different media platforms have different rules for content," Coles explains. "In addition, different types of entities may have different requirements that they have to comply with when it comes to advertising or products. For example, drug manufacturers are subject to different requirements than medical providers. Hers itself is not a drug manufacturer, pharmacy or medical provider. We provide a platform through which customers can access licensed physicians for telemedicine services and can also access certain medications at a pre-negotiated cost from third-party pharmacies who provide products through the platform."

In other words, guidelines for medical services that don't fit into the pre-recognized categories of drug manufacturer, pharmacy, or medical provider are pretty much non-existent.

Instead, telemedicine platforms "comply with content requirements for media platforms we utilize," Coles clarifies. Apparently, that doesn't include disclosing the side effects of the promoted prescription, at least on Facebook and Instagram. "But comprehensive safety information, including risks of side effects, is provided to customers and patients through a number of channels, including through the website, the consultation process and the prescription fulfillment process," says Coles.

Perhaps this is how digital healthcare providers slip through regulatory loopholes. As Vox reported, "According to the FDA, advertisements for pharmaceuticals and medical devices must give a balanced description of the product, meaning an ad cannot focus solely on the benefits of its use if there are known risks that could alter the patient's decision to use a particular product." (Hence, why television commercials for medications are often dominated by a rapidly-recited list of known side effects.) However, without its own social media monitoring system in place, the FDA relies on consumers to flag potential violations of this guideline, either by notifying the FDA Office of Prescription Drug Promotion's Bad Ad Program or complaining to the brand directly — which many did in regard to Hers's admittedly "misguided" post.

"The way that [Hers] is advertising this [is] wrong on so many levels" @esteelaundry said, tagging the brand. (Surely, the company's decision to apologize was driven in part by the attention from the anonymous collective.) "It'll only be a matter of time before influencers begin to push this," the Instagram account continued.

Well, that time is already here. Medical "spon con" is a new social-media staple, with Kim Kardashian promoting a nausea medication for pregnant women (which caught its fair share of backlash), Louise Roe hawking psoriasis cream and plenty of previous "Bachelor" contestants accepting money to promote medical procedures, as reported by Vox. Even though the FTC does have regulations in place for influencers to disclose paid partnerships (#ad) and side effects, its most recent guidelines were published in 2014 — and a lot has changed in both the social media and telemedicine spaces since then.

This is one area where America differs dramatically from international counterparts. "[My] readers from Europe were shocked in general," Shept says of the reactions to the Hers ad. "In a lot of countries, you cannot advertise prescription drugs in this manner." It's true: Virtually every other country, barring New Zealand, has outlawed targeting consumers with ads for medication. The U.S., in contrast, has not only not outlawed direct-to-consumer ads, but it's pretty much invented a new level of medical marketing.

Take this line from the Propranolol sales page on the Hers website: "Performance anxiety can affect more than just how you feel, it can stand in the way of you manifesting your badassery." No, non-manifested badassery isn't a valid medical concern — but it is an effective way to get anxiety meds into the hands of the #Girlboss generation. (And sure, on some level, this message probably speaks to the 27 million Americans suffering from actual clinical anxiety, too.)

When asked if Hers plans to overhaul its marketing approach or ad approval process, Coles says, "We have taken steps to ensure that any future social or marketing materials continue to provide the necessary education around occasional situational anxiety and Propranolol." Education just might be the magic word; the difference between offering prescription medication and selling prescription medication.

Cove and Keeps agree; education has been the backbone of their advertising campaigns since the brands launched. "Thirty Madison brands are full-service solutions for specific chronic conditions and not just medications, so our current TV advertising focuses on these conditions and disease awareness, rather than any specific prescription medication for a particular condition," Gutentag explains.

Considering the somewhat-vague guidelines that have ruled the industry for years, it's unlikely that the FDA or FTC will crack down on telemedicine-specific marketing in a significant way anytime soon. Until legislation catches up to technology, the most effective way to advocate for responsible marketing is to demand better from the brands — and something tells me modern consumers are more than up to the task.

Main/homepage photo: Courtesy of Hers