After Dangling Climate Carrots, Biden’s EPA Brings The Sticks

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Eight months ago, President Joe Biden signed into law one of the biggest clean-energy spending packages the world has ever seen, dangling hundreds of billions of dollars in carbon-cutting carrots for everything from zero-carbon power stations and electric vehicles to lithium mining and hydrogen fuel pipelines.

Now comes the stick. Earlier this month, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed the nation’s strictest standards ever on tailpipe pollution from new cars and trucks sold starting in 2027, giving automakers the option to comply by simply manufacturing more electric vehicles.

Next, the agency is expected to outline an even bigger regulatory step: the United States’ first major controls on greenhouse gases from power plants.

The two regulations would work in tandem to slash overall emissions in the world’s largest economy. While federal data shows that a typical internal combustion engine vehicle emits nearly five times as much carbon per year from its tailpipe, the coal and gas it takes to charge an electric car still produce greenhouse gas ― meaning the decarbonization gambit only works if the U.S.’s nearly 12,000 utility-scale generating stations stop using unabated fossil fuels. Of the more than 3,400 power plants in the U.S. that only burn fossil fuels, fewer than 20 currently capture their emissions.

The proposal ― details of which The New York Times and The Washington Post published last week ― will likely set standards so tough that new or existing gas and coal-burning stations would need to either equip smokestacks with costly technology to capture carbon dioxide before it enters the atmosphere, or, in the case of gas plants, to swap methane fuel for hydrogen, which emits no carbon when burned. The other option would be to shut down.

The EPA told HuffPost it would release the regulation as early as next week.

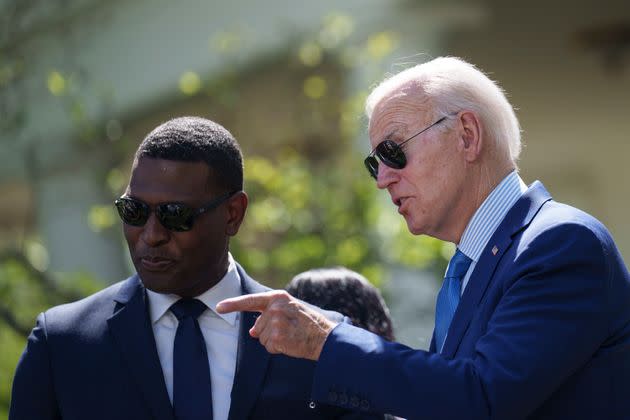

President Joe Biden talks to Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Michael Regan in the Rose Garden of the White House, April 21.

Enacting any federal regulation takes months of hearings and public comments, but this rulemaking could be among the Biden administration’s most contentious, and would likely trigger legal challenges from Republican states.

Fossil fuels ― primarily methane gas and coal ― produced over 60% of U.S. electricity last year and a quarter of its greenhouse gas pollution, making them the second-largest source of such pollution after automobiles. States’ varying systems of regulating power plants, with an even more diverse array of laws to cut carbon emissions, have created a Balkanized American grid system, with some states still heavily dependent on coal while others generate much of their power from gas, solar and wind.

But the trio of laws Biden signed in his first two years as president, the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the CHIPS and Science Act, directed billions in U.S. support for building power lines, restoring existing nuclear power plants and manufacturing microchips in the U.S. The Inflation Reduction Act, which Democrats passed in a narrow party-line vote last summer, was the biggest yet, with nearly $400 billion in tax credit for zero-carbon electricity and electric vehicles.

New federal incentives for carbon-capture equipment and infrastructure, including pipelines to ship the carbon dioxide and wells in which to store it, are expected to drive that number upward. But critics of the technology, ranging from environmentalists to fossil fuel hard-liners, say the costly technology will drive up energy prices, making renewables the cheaper option when grid planners build new power stations. And Republican-led states are already gearing up to sue the Biden administration in a bid to keep the regulation from ever taking effect.

That playbook worked the last time a Democratic president tried to regulate power plants’ carbon emissions.

When the Obama administration tried regulating such emissions in 2016, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the GOP attorneys general who asked to temporarily block implementation of the so-called Clean Power Plan.

The decision hinged on the Obama EPA’s interpretation of a hotly debated clause of the Clean Air Act to justify allowing power plant owners to offset the emissions of a fossil fuel station in one location by building more zero-carbon generation at another site. The scheme was meant to give utilities options to comply with the rule. Instead, it created an opening for opponents, who claimed the bedrock 1970 law limited federal regulators’ authority to dictating only solutions that could be applied “within the fence line” of an individual power plant.

President Donald Trump looks on as EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler speaks during an event to unveil significant changes to the National Environmental Policy Act, in the Roosevelt Room of the White House, Jan. 9, 2020.

Before the Obama administration could resolve the high court’s legal questions, Donald Trump won the presidency and nominated Scott Pruitt, the former Oklahoma attorney general who spearheaded the lawsuit against the Clean Power Plan, as the new EPA administrator. The Trump administration quickly rescinded the regulation altogether.

Though the Republican administration rejected federal scientists’ own warnings about the severity of climate change, a 2007 Supreme Court ruling required the EPA to regulate carbon dioxide as a pollutant under the Clean Air Act, meaning Trump couldn’t simply do away with the rule. His EPA had to replace it.

In 2019, the EPA ― now under Trump’s second administrator, former coal lobbyist Andrew Wheeler ― finalized the Affordable Clean Energy rule, which focused exclusively on fixes within power plants’ fence lines. In a twist, regulation actually gave power plants the incentive to burn more coal, as long as the station complied with modest efficiency improvements.

That regulation, too, was overturned on a technicality. The Trump EPA had sought to cement its definition of the Clean Air Act’s contentious “fence line” provision. On those grounds, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit struck down the ACE Rule on Jan. 19, 2021, Trump’s last full day in office. Soon after, the Biden administration declined to defend the regulation in court, effectively leaving the U.S. without a federal climate rule for power plants.

While Biden focused his efforts with Democratic control of Congress on enacting federal incentives, the Supreme Court agreed to hear a Republican case on Trump’s ACE rule. The unusual decision to wade into a regulatory case with no real stakes ― the Biden EPA had no plans to implement the ACE rule regardless of the legal ruling ― was widely seen as an effort by the high court’s new conservative supermajority to hamper the EPA’s ability to regulate greenhouse gas emissions.

The AES Corporation 495-megawatt Alamitos natural gas-fired power station is seen on Oct. 1, 2009, in Long Beach, California.

Last June, the court ruled that Trump’s fence line definition was correct, closing off what had already become an unlikely avenue for the EPA to try again to regulate power plant emissions. Rather, utility lawyers at the time warned that the decision would all but force the Biden administration to take a more drastic and incontestably legal approach to slashing emissions, by effectively banning fossil fuel plants without carbon-capture equipment.

While the decision “rejected the legal interpretation underlying” the Clean Power Plant, the court “affirmed EPA’s ‘traditional’ authority to set pollution control standards that make power plants ‘operate more cleanly,’” said David Doniger, director of the climate and clean air program at the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental group.

“Then Congress put a further stamp of approval on that authority in the Inflation Reduction Act just a few weeks later,” Doniger wrote in an op-ed for the trade publication Bloomberg Law, arguing that the new regulations stood on “strong legal footing.” “The EPA is now poised to propose new standards for power plant carbon pollution based on the clear legal pathway that the Supreme Court and Congress provided.”

Another factor making the fate of Biden’s rules hard to predict is the administration’s simultaneous wave of new regulations on mercury emissions, coal ash storage and particulate matter pollution.

“Each rule is moving independently, but they all impact power plant operations,” Julie McNamara, a senior energy analyst at the nonprofit Union of Concerned Scientists, wrote in a blog post last week. “The full suite of rules also gets reflected down the line when state regulators are evaluating the relative economics of a given power plant facing multiple compliance requirements compared to clean energy alternatives.”

Getting these standards right “will take a lot,” she added.

“Furthermore, a lot of vested fossil fuel interests will be attempting to undermine them,” McNamara wrote. “EPA holds enormous responsibility on behalf of people and the environment as it navigates this path.”

Clarification: This story has been updated to describe how electric vehicle charging typically compares with internal combustion engine vehicles in terms of emissions.