The dark side of America’s welcome home: Vietnam vets recount harassment and disrespect

I was not prepared for the number, quality and intensity of responses we received after requesting homecoming recollections from Vietnam vets.

Wayne Smith of Warwick earned his Combat Medic Badge with the 9th Division in the Mekong Delta. He painted an especially graphic picture of his “reintroduction to the world,” as we described it back in the day. Returning vets flew into West Coast Air Force bases. They received a good meal, vouchers for civilian flights home, and a bus ride to Seattle, Oakland or San Francisco Airport.

“Once we arrived at SFO, soldiers rolled into any store that sold pants, shirts, vests…anything that made them look like everybody else,” Smith wrote. “The men’s room was like a scene from 'The Twilight Zone.' The dank space was full of veterans changing clothes. Every trash can was overstuffed with discarded Army uniforms!”

More:Boston Bruins recognition of Vietnam veteran was a long overdue welcome home

I’m having trouble getting that image out of my head. Imagine, American soldiers, reluctant to advertise to their own countrymen that they were on their way home from war.

This was an overreaction to horror stories they heard from replacements joining their units about how returning servicemen were being treated.

Unfortunately, the stories were repeated so many times in Vietnam they became magnified, both in frequency and content.

As waves of veterans returned in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the nation was locked in bitter debate about the war. Two weeks ago I wrote, "Many families (including my own) were split by the antiwar movement."

One reader pointed out that was an inaccurate statement. “It was support of or opposition to the war itself that split families,” she wrote, correctly pointing out that my statement blamed only the antiwar faction. This demonstrates how deep this divide still runs, 50 years later.

"Men who fought in World War II or Korea might be just as haunted by what they had personally seen and done in combat," Arnold R. Isaacs writes in Vietnam Shadows: The War, Its Ghosts, and Its Legacy. "But they did not come home, as Vietnam vets did, to a country… full of doubt about why those wars were fought and whether they had been worthwhile.”

Peter Larkowich grew up in Olneyville. He graduated from Providence College in June 1967 and was in basic training by August. Assigned to the 95th Military Police Battalion, “We escorted convoys, did security at the Saigon Port and manned guns on Navy PBRs (patrol boats),” he wrote.

“On my way home, I got heckled and yelled at twice. I thought they were immature and uninformed. I was out of Vietnam, I was safe and I did not care.”

He did go into a Levi’s store, however, and bought jeans for the plane ride home, “just as a precaution”.

Elizabeth Cimini of Warwick wrote about her husband, who died in 2017. ”Joe came home January 2, 1970. He was wildly welcomed by his family at TF Green, but he had been harassed at another airport on his way here. When he interviewed for one job, he was told he couldn't be hired because "All Vietnam vets are crazy."

The workplace was not always supportive and welcoming. East Providence native Frank Capecci recalls, “My parents and my fiancee met me at the airport. My fiancee's boss would not give her a full day off to be with me. She had to go back to work immediately after our brief reunion.”

Veterans face confrontation

Army Capt. Larry Reid of Warwick wrote, “We heard about the anti-war sentiment but I was not prepared for the hostility.”

Returning from his tour with the 5th Infantry Division, he had a day to kill in San Francisco awaiting his flight. He decided to walk around Fisherman’s Wharf. “I was wearing my Class A uniform, and the weather was really nice.”

He was accosted by a “street person” who sneered, “Kill any children today, Captain?”

Reid didn’t respond. But a nearby police officer saw the confrontation. “As he pushed the offender away both the officer and I were spit at and called ‘Nazis.’ " The policeman said, ‘Sorry about this, Captain. Are you coming home or headed over?’ I said I was headed home to Rhode Island. He said, ‘Welcome home.’”

Harry Wadsworth served on Coast Guard cutters off the Vietnam coast. On his San Francisco-Boston flight, a few Americans showed contempt for the military.

“While waiting at baggage claim one of them called me a baby killer and spit on my uniform. I lost my cool and dropped the jerk.”

A policeman asked why Harry had slugged the guy. He repeated what had happened. “The cop said, ‘Grab your luggage and welcome home from a former Marine.’”

Harry read this to his wife who said, “Make sure they know you were in uniform the whole trip. And that after you knocked him down you threw him into the baggage chute.”

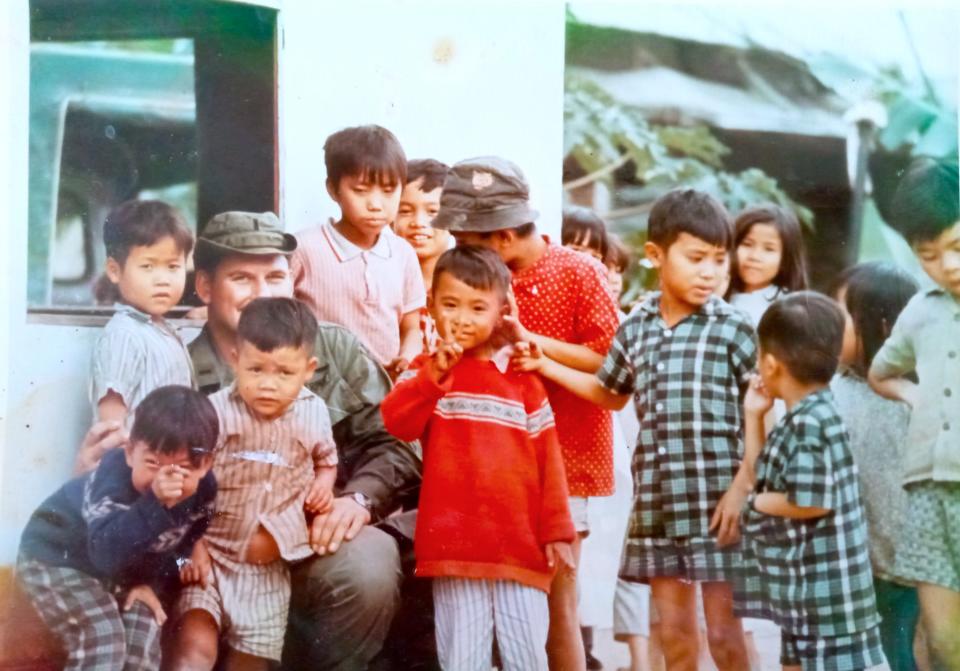

Mike “The Owl” Patalano of Providence returned from a year advising the South Vietnamese Army.

”I had a lot of steam to blow off,” he wrote. “I was going to the bars and dance clubs every night. One night a young lady asked what I did for a living. I said I just got back from Vietnam."

"‘Why the F did you go there?’ she asked. ‘Why didn't you go to Canada? You're a f**king animal.’ From then on I hardly ever talked about my Vietnam service.”

Such people wrongfully blamed American troops for the tragic situation in Vietnam, instead of the government leaders who sent them there.

"Some protesters did not make a distinction between the war and those who fought it, and they regarded American soldiers as ready and willing killers or ignorant dupes," Christian G. Appy explains in Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam.

Bert Guarnieri came home and started working for the Post Office in Providence. “Groups of kids would come down from College Hill, chanting and carrying protest signs. My supervisor knew I was a Vietnam vet and asked, ‘Does that bother you?’ I said, ‘Not the protesting part, because that’s why I joined in the first place, to protect their right to speak their minds.’”

What did bother Guarneri was a protester carrying the North Vietnamese flag. “That went up my butt a mile — the enemy's flag! — so I ran across the street and got into it with the guy. Yeah, I kinda ripped it out of his hands and threw it on the ground and stepped on it like they did with the American flag. But I was doing it to the friggin’ enemy's flag.

“You want to protest, that's fine and dandy. But don't come carrying the enemy's flag. That means you're an enemy. You’re supporting those who killed many of my friends, and tried to kill me.”

Such heated arguments kept many people from welcoming returning veterans or recognizing their service. "Ignoring the Vietnam vet was just one part of the more general phenomenon of ignoring the nation's entire, shattering, unhappy Vietnam experience in all of its aspects," David Levy writes in The Debate over Vietnam.

Vietnam veterans face indifference arriving home

Fortunately, violent confrontations between veterans and protesters were rare. Instead, most servicemen returned to a society that did not seem to care.

"Society as a whole was certainly unable and unwilling to receive these men with the support and understanding they needed," Appy writes. "The most common experiences of rejection were not explicit acts of hostility but quieter, sometimes more devastating forms of withdrawal, suspicion, and indifference.”

This indifference affected Philip Salois — born in Woonsocket and raised in California. He was drafted in March 1969 and ended up in combat with the 199th Light Infantry Brigade. In March 1970 he earned a Silver Star for rescuing wounded comrades under fire.

“My transition back to civilian life was relatively easy,” he wrote.

“However, no one wanted to know anything about my war experiences, so I went into my Vietnam closet for many years. It wasn't until 1983 that I finally admitted I was suffering from mental anguish about the war and needed help.”

Wayne Smith wrote, “I saw people just living their lives, going to work, to school or the beach. I felt profound sadness; those people don’t give a damn about us, or that we’ve just returned from fighting a war for the USA.”

Larkowich noticed that people’s eyes would glaze over when Vietnam came up, and the subject would change.

“I wondered why they did not care about what really happened. They drew conclusions based on misinformation and didn’t want factual, first hand experience. My own family fell into that category.”

John Kerry, a Vietnam veteran prominent in the antiwar movement, became a U.S. senator. He wrote, “The country didn't give a [care] about the guys coming back, or what they'd gone through. This treatment made many veterans feel alone and isolated from the rest of American society.”

We formed Vietnam Veterans of America when the traditional veteran groups did not welcome us or address our needs. We came to rely on each other.

To be fair, not everyone was treated badly, or even with indifference. Returning veterans who stayed in the military were often insulated from much of the negativity and found an understanding support system.

Family and friends of a West Point classmate threw a formal dinner dance to welcome him home; more than 100 people attended. Jane Calhoun, widow of long-time Newport resident and Navy pilot Bill Calhoun, wrote, “Thank heaven his community [Thomasville GA] welcomed him home warmly. I wish it had been so for all our Veterans.”

Americal Division veterans Jim D’Agostino and Hank Suffoletto served in the same unit and flew home together. “Hank's father picked us up at Hillsgrove,” recalls D’Agostino. “It was uneventful. Everyone was happy to see us.” Suffoletto went on to a 40-year career with the telephone company, while D’Agostino eventually went back into the military. He joined the Air National Guard and enjoyed a very successful career, retiring as a brigadier general.

As an aside, he is the only Air Force general I know who is entitled to wear the Combat Infantry Badge.

William Taylor, 1968 URI ROTC grad, summed it up nicely. “I was welcomed home by a loving wife, a 3-month-old son and my parents. My family’s love and understanding made all the difference! I also continued to serve in the Army which was good medicine. Eventually, I learned that all Americans are my friends and all veterans are my heroes. It was great to be home!”

To this day, when I meet a fellow Vietnam vet, chances are we will embrace and say “Welcome home, brother.”

ANNOUNCEMENTS

Attention Vietnam vets: Share your feelings about any aspect of your Vietnam experience: March 29 marks the 50th anniversary of the withdrawal of the last U.S. troops from Vietnam. The March 27 column will address your feelings about the war, then and now. Email me at veteranscolumn@providencejournal.com

CALENDAR

Tuesday, Feb. 21, 7-8:30 p.m.; FREE ticket to Letters From Home: The 50 States Tour, McVinney Auditorium, 43 Dave Gavitt Way (Westminster Street near the Cathedral). This is a high energy performance in the style of a USO show. Tickets are on sale for $26, but veterans can request free tickets by emailing Erinn Dearth at

erinn@firstinflightentertainment.com

To report the outcome of a previous activity, or to add a future event to our calendar, please email the details (including a contact name and phone number/email address) to veteranscolumn@providencejournal.com

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Vietnam veterans faced scorn and rejection when returning home to RI