'The dark side of globalization.' What Bellarmine students learned at the US-Mexico border

Shadows cast by the U.S. border wall provide cover for worlds of exploitation, suffering and death. Extending north and south, fiefdoms of drugs, human trafficking and violence have emerged from thriving narcotics and gun markets, harmful immigration policies, and prejudice. We should be honest enough to acknowledge our connections to the misery.

For three years Bellarmine University has supported an immigration course that includes a trip to the border. This year, a group of honors students spent spring break peering into these shadows to better understand why the zone separating the U.S. and Mexico is awash in blood, from wounds old and new. Knowledge is especially important as changes in immigration policies intensify the highly politicized debates that follow these issues.

Opinion: I am a student who spent spring break at the Mexico border, I saw the horror migrants face

Beyond the profound moral questions raised by such conditions, we should think about what is going on here geopolitically. Social scientists have identified the emergence of narco- and necro-states, the former run by powerful and ruthless cartels, and the latter the result of policies and practices that mean significant groups of underprivileged people are more likely than others to be subjected to violent death or good-as-death conditions.

The existence of transnational boogeymen is not especially novel information. But the degree to which violent groups operate with virtual impunity – outside the controls of sovereign states – should stop us in our tracks. A more serious question is whether this represents the dark side of globalization and a glimpse of a future most would not care to see.

There is increasing evidence that immigrant farmworkers in the U.S. are falling under the control of cartels, as they extend their interests in smuggling and gun-running. Cartel-controlled workers are isolated and exploited in the fruit and marijuana industries of states such as California, Oregon and Washington. In the more traditional business of illicit drugs, fentanyl – the cartel product du jour – is a most deadly specter haunting the shadows, which fall over too many Kentucky homes.

More: Marijuana wars: Violent Mexican drug cartels turn Northern California into ‘The Wild West’

Cartel death and violence is often grossly public, reflecting operations in both the narco- and necro-states. But there are other, less visible actors that contribute to suffering and loss of life, and this was the focus of the Bellarmine border trip. Specifically, we witnessed how prejudice, policy and practice significantly enhance the vulnerability of the most vulnerable.

We have historically applauded those trying to pull themselves up by their boot strings. But when that boot string is in the form of a rope ladder tossed over the border wall, many want to snip the lifeline. Prior to traveling to Arizona, students studied Prevention Through Deterrence and other border policies that use Border Patrol agents and technology to deter crossings into populated areas, and instead funnel migrants into hostile environments, such as the Sonoran Desert. The “deterrence” factor is often death by multiple means.

What does that death look like? In a collective sense, it is a mass of dots on a map maintained by Humane Borders, a humanitarian group from Tucson. In an individual sense, it looks like Orlando Suarez Flores, a 22-year-old man who died of hyperthermia just outside a middle-class neighborhood in Nogales, Arizona. Students joined artist Alvaro Enciso in planting a cross to memorialize the death of someone their age whose dreams ended in a patch of pigweed. Alvaro has planted nearly 1,000 such crosses, and the count grows each week.

Our southern border has not always been fortified. Fences were erected during skirmishes, but formidable walls started to emerge in 2006 with The Secure Fence Act. Donald Trump, in his compulsion to make things bigger, had much of the original wall removed and replaced with a behemoth surpassing 30 feet tall in places. This did not stop desperate people; it just upped the potential for suffering. On the Mexican side, coyotes added a few feet to their ladders. On the US side, migrants who topped the wall could lose a grip or get spooked by Border Patrol, falling faster and harder to their death.

That appeared to be the fate of Otilio Serrano Garay, 34. The Office of the Pima County Medical Examiner listed his death as blunt force trauma to the head. His body was found at the foot of the wall on the US side. We planted a light green cross in the shade of an Emory oak tree to recognize his death.

More: Native Americans face a deadly drug crisis. How tapping into culture is helping them heal

Necro-state power is rooted in the potential for death, or at least a life that is daily haunted by that potential. The boundaries of this “state” are fluid and extend in all directions. What seemed different about this year’s trip into that zone was that it appears to be a more normalized situation, with armed actors openly stalking this militarized – but erratically governed – space.

As we traveled the wall with two members of the Tucson Samaritans, a humanitarian group offering aid in the borderlands, we were confronted by a member of a militia group that has set up camp on the U.S. side of the wall. Well-armed and dangerously self-righteous, they have appointed themselves as caretakers of the motherland, protecting us all from migrants and pedophiles. This particular militia member wanted to know our business and wrapped up the interrogation with a volley of bible quotes. Others were gathered in small camps or under a large white tent that presumably was home base.

On a separate day, at a large gap in the wall (surprisingly, there are lots of these), we spotted several people on a hillside just over into Mexico. We exchanged greetings, and a man in camouflage slowly descended and approached the border. In our 20-minute conversation, we learned he was a cartel scout looking to assist two people from Oaxaca, Mexico on their border crossing.

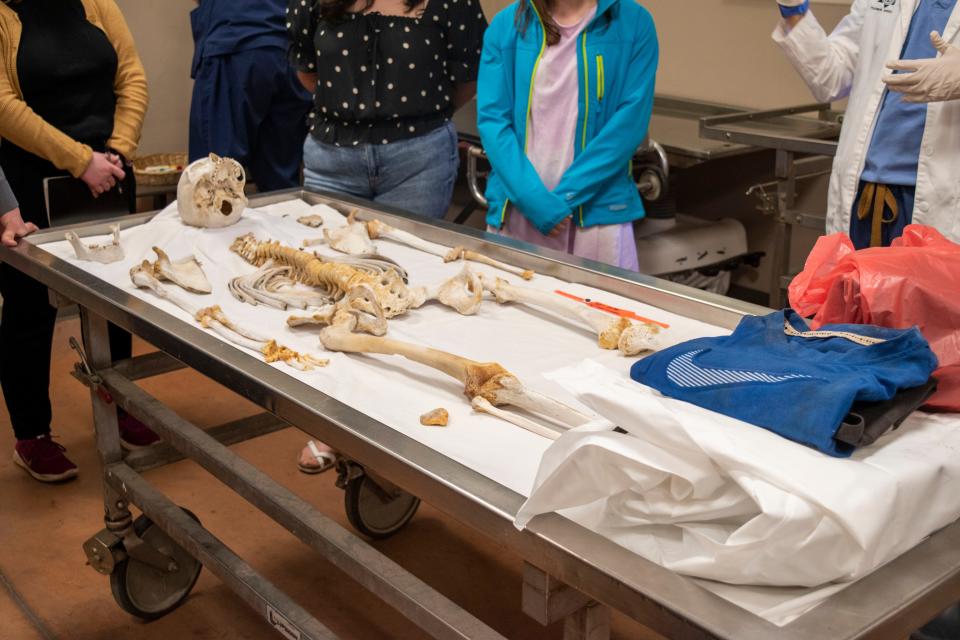

The Bellarmine immigration class is based on the belief that experiential learning adds important knowledge to undergraduate education. In addition to various engagements with the wall, we stood around a migrant skeleton at the Medical Examiner’s office as a forensic anthropologist explained how they identify remains so family members can have closure. We hiked in the desert with Humane Borders, sensing firsthand how heat, menacing vegetation and rocky terrain wear down life force. The lone caretaker of a mining ghost town told us of visits by armed cartel members and desperate migrants, including a 14-year-old boy with Down Syndrome who came down from the hills looking for nothing more than a hug.

Contentious issues are charged with ideologies and power. This is all the more reason to ask hard questions and seek answers wherever there might be enlightenment – even if a wall stands in the way.

Dr. Frank Hutchins is a Professor of Anthropology at Bellarmine University

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: What a spring break trip to the Mexico border teaches college students