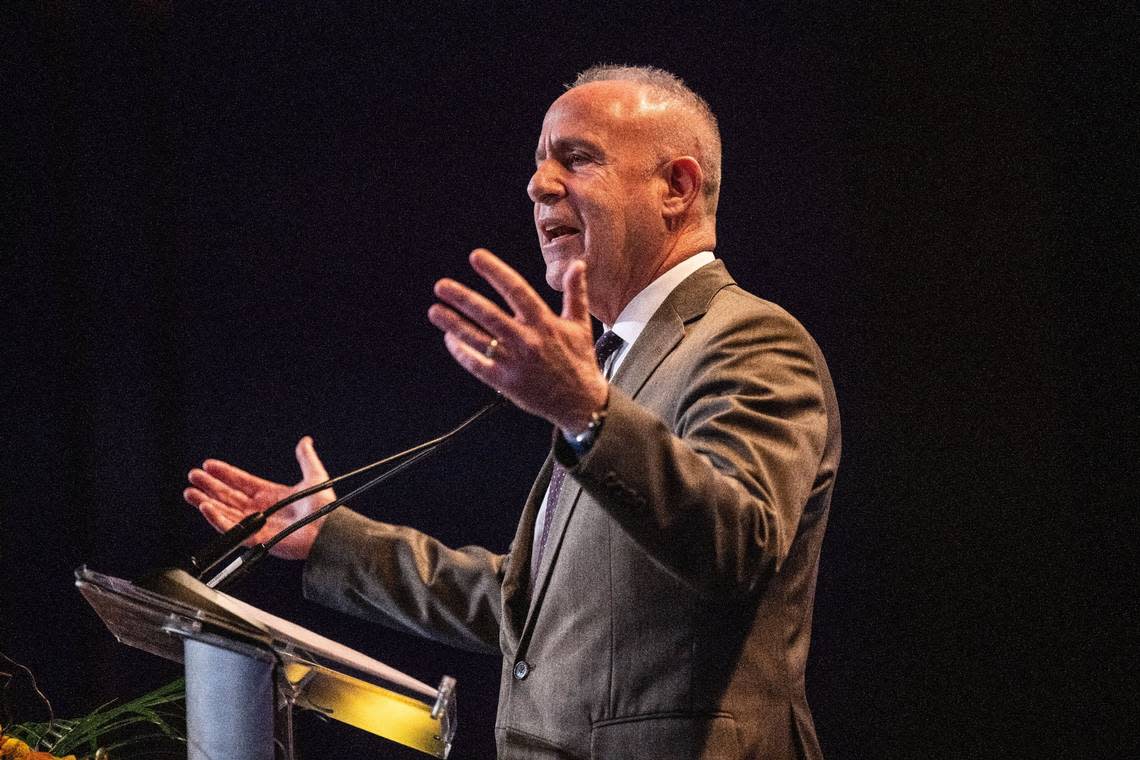

Darrell Steinberg ranks at the top among elected officials in the Sacramento region | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

If there was ever an incoming Sacramento mayor poised to dominate the regional stage, it was Darrell Steinberg in 2016. His resume was unparalleled, from his leadership of the California state Senate to his years as Sacramento city councilman to his statewide political connections.

Any truly regional Sacramento mayor would have the home base of operations at the Sacramento Area Council of Governments. SACOG is the 31-member body of local leaders that advance our transportation planning. Only at SACOG can a Sacramento mayor rub shoulders with his political peers in El Dorado, Placer, Yuba, Yolo, and Sutter counties on a monthly basis.

Opinion

But like his immediate predecessor, former Mayor Kevin Johnson, Steinberg decided not to try to be a regional mayor from City Hall. He had already laid the groundwork for an impressive legacy as a regional force as senate pro tem.

No one has accomplished more in flood control in modern history than Darrell Steinberg. Extraordinary improvements to flood protection took place, from the mega-levees now protecting Natomas to the new emergency spillway on Folsom Dam to levee improvements on the American River to at-risk Sacramento streams.

“Darrell brought it every day — incredible drive and ability to make changes in the city that he loves. Sometimes people felt he pushed too hard. But that is not how he’s wired,” said Mike McKeever, the former SACOG executive director. “Some of his biggest accomplishments will only become evident through future years.”

The accomplishments were many. Senate Bill 276, authored by Steinberg in 2007, directed the state to participate in numerous flood control projects on the Sacramento and American rivers. And the state did. SB 276 resulted in a long-lasting, functioning marriage between the state and the Sacramento Area Flood Control Agency, a regional entity created after the floods of 1986 that made greater Sacramento so much safer. It was SB 276 that helped the state and the flood agency to nurture a broader coalition including Yolo County, and brought federal funding to the area through the work of Congresswoman Doris Matsui.

Steinberg’s regional legacy on transportation planning is more complicated and also started during his legislative years.

Senate Bill 375 of 2008 marks one of the most important advances in climate change of that era. It directed the California Air Resources Board to set regional reductions for greenhouse gas emissions and for regional governments like SACOG to achieve these reductions through their long-term transportation plans. In simpler terms, it sought to stop a decades-long pattern of expanding sprawl and building new highways to solve our self-created problems. Locally, it led SACOG to struggle with what to do about the SouthEast Connector, a new continuous expressway from Highway 99 to Highway 50 via Grant Line Road.

SB 375 faced a test in Sacramento County in 2020. Backers of a sales tax hike dedicated to transportation projects sought to fund the full connector road along with a lengthy menu of other improvements. A previous transportation sales tax effort had barely failed to reach the two-thirds approval threshold in 2017.

Steinberg’s support in 2020 was key.

This was when he flexed the most regional muscle in his mayoral history.

Steinberg refused to support any transportation plan that did not meet the emission-reducing goals of his 2008 legislation and those that SACOG later established. The proposed measure at the time failed to pass the SB 375 test. In March 2020, he said, “I believe it is just common sense that the finance plan must be consistent with the region’s clear commitment to reduce (greenhouse gas emissions) by 19 percent.”

This upset some powerful friends that frankly deserved to be upset. Compromise language was reached to ensure consistency with SB 375, through the courts if necessary.

He had won though it turned out to be a hollow victory.

A court ruling elsewhere in California created a new possibility of raising sales taxes for transportation by a mere voter majority — if it was placed on the ballot by voter signatures as opposed to a governing body. That is a big “if.” The court ruling transferred political power on local transportation financing from the elected officials to private interests that could gather the political signatures to get a local initiative on the ballot.

The champions of roads tend to have money. The champions of transit, not so much.

This new signature-gathering initiative created a very different Measure A. It was not a political compromise. It embodied the dreams of the financiers.

Measure A called for billions of dollars in new roads beyond the SACOG plan and beyond the 2020 compromise language that was largely the wordsmithing of Steinberg at that time. The revenue to fund these roads was baked into the language of Measure A.

Yet Steinberg ended up supporting the measure.

He attributed his support to a separate agreement between SACOG and the Sacramento Transportation Authority. It committed STA to funding road projects that met emission-reduction targets.

Because this subsequent agreement was not in the language of the ballot, it was automatically subject to revision. The bottom line of this Measure A: The backers of new roads would be guaranteed 40 years of sales tax money. They would have time to time to rewrite this non-binding SACOG-STA deal. Steinberg supported it anyway.

“In the short to medium term, the politics of SACOG would not allow it,” Steinberg told The Bee Editorial Board last October. “Because, frankly, the other five counties aren’t necessarily predisposed to making it easier to build projects in Sacramento. That is the makeup of the makeup and the voting blocs as they exist in SACOG.”

Had Steinberg opposed this Measure A, he would have been at odds with various long-time political allies such as Measure A consultant David Townsend. He would have been right on policy, to not fund things that make no environmental sense with the region’s own emissions reduction plan.

He chose otherwise and he lost. Nearly 56% of voters rejected Measure A.

In hindsight, It had two glaring challenges. It was a new tax, never popular. And it was a badly and spectacularly road-centric vision of Sacramento County’s future that was fueled by money from the beneficiaries of Measure A.

While Steinberg lent his name to support the measure and made a few command performances, he did not campaign aggressively for Measure A. For a leader not known for going halfway on anything, his passiveness said something.

Taking a step back, Steinberg’s regional legacy may not be all that it could have been. He could have found the time and energy to play outside of the city of Sacramento. He did not.

I really wish he had chosen otherwise.

That said, in my 32 years watching things here in Sacramento, Steinberg ranks at the top of the list of local elected officials.

Nobody other than Steinberg has such an impressive regional legacy, though he did most of that work before he became mayor of Sacramento.