Daughter of L. Brooks Patterson fights Pontiac plan in run for Oakland County executive

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

There’s a new Patterson running for the top office in Michigan’s most affluent county.

Despite a storm dumping rain outside, more than 400 people crammed Clarkson’s Deer Lake Athletic Club last week, as Oakland County’s newest politician named Patterson — Mary Margaret — pledged she’d “bring back the Oakland County my father fought for every day of his life.”

That moment was a shining one for Republicans, letting them rally around a name synonymous with decades of election victories, forgetting that Oakland County had swung from red to blue during the 26 years that the late L. Brooks Patterson ran county government. Last week also shined as a highlight of how Mary Margaret Patterson differs from her opponent on urban issues. The contrast runs to the heart of how Republicans have differed from Democrats for nearly a century, ever since Richard Nixon discredited the urban programs of his predecessors, from Lyndon Johnson and John F. Kennedy all the way back to Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Nixon's tactic, according to many scholars of American political history, became the Republican approach to poverty and urban problems, which, put simply, is to run against the Democrats’ approach.

Oakland County will hold a primary election next year, and others may enter the race for county executive. Still, in the 2024 general election, Mary Margaret Patterson, having received the full endorsement of the Oakland County Republican Party, presumably will face the incumbent Democrat, former Ferndale mayor David Coulter, who has been Oakland County Executive since shortly after Patterson’s father died.

Last week, the day after Patterson officially announced her campaign, the 19-member Oakland County Board of Commissioners voted along party lines to support Coulter’s momentous urban proposal for Pontiac. He wants to move hundreds of county employees into largely vacant office buildings in downtown Pontiac. Helping Pontiac is "the moral thing to do," but it also helps the county, according to Coulter’s calculus. That conclusion springs from a lengthy analysis by professional consultants of the firm Plante Moran, which showed that the move, financially, might be a wash, because rehabbing Oakland County’s aging stock of government buildings would cost nearly $1 billion.

In that light, buying and renovating two office buildings in Pontiac — former GM sites — would allow the county to close its most antiquated office space, argues Coulter and his Democratic allies on the county commission. The county’s offer, almost sure to be approved by the Pontiac City Council, includes assuming the lease for the city-owned Phoenix Center Parking Structure, which Patterson points out is in serious disrepair, is hardly used anymore and seems destined for demolition, the path suggested a dozen years ago by former Pontiac Emergency Manager Lou Schimmel. But Patterson firmly opposes moving county workers into Pontiac, where they will be forced to pay the city’s income tax.

"The Democrats say they’d be leaving buildings that are decrepit. I say there is no building on the Oakland County campus that needs millions and millions of dollars to fix up. I’ve been in those buildings and they look OK to me," she said. “They’re buying all these buildings that will need a tremendous amount of repairs. I think $120 million is the number I was given. My father worked to put all the county employees on the same campus."

It was in the 1960s and early ‘70s when “urban renewal” was the wonky rage. That's when Oakland County officials moved their operations from the county seat of Pontiac to open land at the city’s far west border, and later beyond that. The county courthouse was first, moving in 1959; the county jail was last, in 1972. The result is there are 15 county buildings on the Pontiac side of Telegraph and another dozen on land west of that boundary. Compared to Macomb County, where key buildings are in downtown Mount Clemens; and Wayne County, whose county buildings are in Detroit. Each is the respective county's seat.

“My office is actually across Telegraph, in Waterford,” Coulter said last week. Then he made the case for applying to Pontiac the Democratic Party’s long-standing tradition of aiding distressed urban areas with public money, whether or not their residents are people of color, and with no guarantee of a return on investment for taxpayers. Pontiac is about 60% Black and 20% Hispanic, according to the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments (SEMCOG).

“For too long, corporations and institutions have moved out of our cities,” Coulter said, referring in Pontiac’s case to GM and Oakland County government both moving out. Was that white flight?

“I couldn’t tell you. I wasn’t there at the time. Now, I just think it’s the moral thing to invest in our county seat. But I want to be clear. This has a benefit to the county. We can take some of our worst, oldest buildings off-line, maybe sell some of them,” he said. Right now, the county has available $50 million in federal COVID-19 aid through the state and another $10 million in direct COVID-19 funding from Washington, Coulter said. As mayor of Ferndale, he said he had seen that city’s downtown transformed and that “the same potential exists in Pontiac.”

Patterson isn't alone in opposition. Every Republican on the county commission voted against the deal. County Commissioner Mike Spisz, of Oxford, the board’s Republican caucus chair, echoed others in calling it wasteful. The private equity firm that owns the office space in Pontiac is “under water for millions of dollars, but the county will be giving them a substantial profit,” Spisz said, standing in the noisy pro-Patterson crowd at last week's event.

The contrast in views is a microcosm of how the two parties approach urban problems. One side favors government investment in urban needs, the other wants to insulate government from urban problems and, often, from their racially diverse settings. Republicans argue the nation’s cities brought urban decay on themselves, and that "poverty programs" do more harm that good; while Democrats blame urban ills on disinvestment and racism, according to the analysis by a professor of geography and planning at the University of Toronto, Jason Hackworth, in his 2019 book “Manufacturing Decline: How racism and the conservative movement crush the American Rust Belt.” Hackworth sides with the Democrats' view.

A decade ago, Coulter’s presumed opponent was known as Mary Warner when she taught fourth grade in the Waterford School District. In 2019, she was Mary Patterson Warner, mourning the death of her father.

Now, she is Mary Margaret Patterson, and with no previous political experience, she began the race for her late father’s office at his favorite watering hole, a private club in Clarkston. It's a four-minute drive from the family home, where she’s raising four children ages 10 to 17 with her husband, Gary Warner, who owns a landscaping firm.

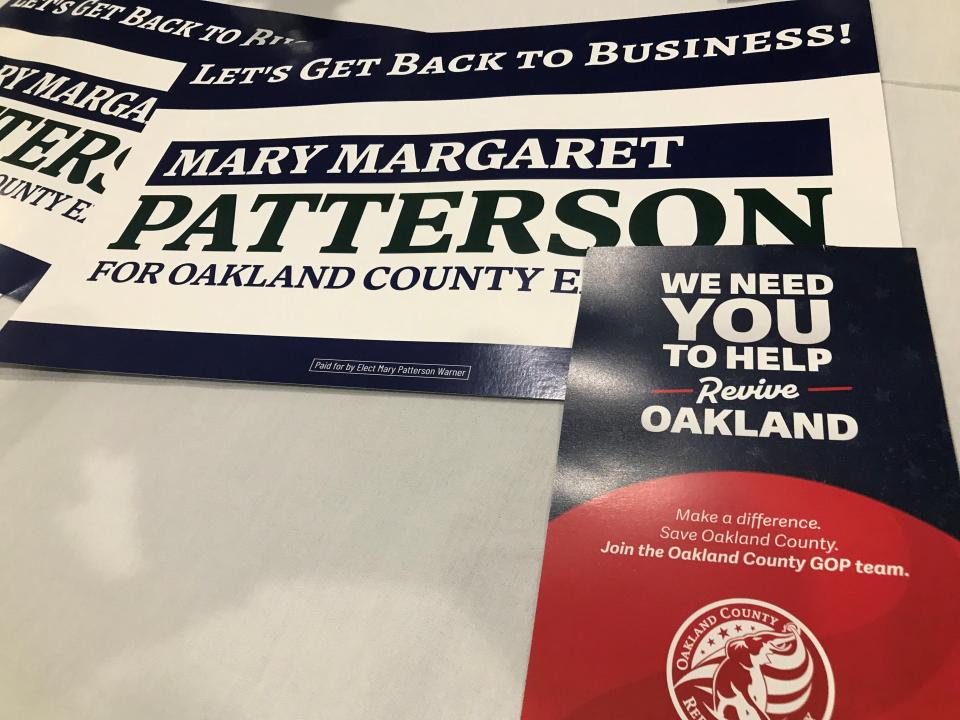

In the crowd were hundreds of her father’s former pals and contributors, leading the new Patterson to tell them, “Write your next check to Mary Margaret Patterson for Oakland County Executive, and let’s get back to business!” The last five words are her campaign theme.

If elected, she might be able to roll back Coulter’s plan to invest in Pontiac, although she’d need a Republican majority on the county board of commissioners. It now has a 13-6 majority of Democrats. Underway is a 60-day period of due diligence, as leaders and their staffs investigate details of the complex deal and try to secure funding from Lansing, Pontiac Mayor Tim Greimel said last week in a state-of-the-city speech delivered shortly after the county board voted.

“If all critical elements ultimately align ... we will welcome county employees with open arms back to downtown Pontiac, which has always been the heart of Oakland County,” Greimel, a Democrat, told the crowd of well wishers, to loud applause.

Contact Bill Laytner: blaitner@freepress.com

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Mary Margaret Patterson fights Pontiac plan in bid for Oakland exec