'My daughter is missing': New laws fail to shield Indigenous women from higher murder rates

ABOUT THIS SERIES: "A Crisis Ignored" focuses on missing and murdered Indigenous women and the grassroots movement to draw attention to disproportionate levels of violence against them. USA TODAY Network reporters in nearly a dozen states worked for more than a year to examine the factors that contribute to the crisis and how laws enacted in many states and at the federal level have largely failed to address it.

LAME DEER, Mont. — When a police officer walked into the Cheyenne Depot, a convenience store on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in southeast Montana, Malinda Harris Limberhand knew this was her chance.

It was July 4, 2013, and Malinda hadn’t heard from her 21-year-old daughter, Hanna Harris, since she’d left to watch fireworks the previous night. Malinda babied her “Hanna Bear” or “Hanna Banana,” but her youngest daughter was now a mother herself. Hanna's son, Jeremiah, was 10 months old and wasn’t taking his bottle. He was hungry, and Malinda was worried. It wasn’t like Hanna not to come home to breastfeed him.

Leaving the counter where she worked, Malinda approached the Bureau of Indian Affairs officer. “My daughter is missing,” she said. “When can I file a report?”

She said the officer told her she’d have to wait 72 hours.

Seventy-two hours! Malinda thought. That’s too long. I need to find Hanna now.

Malinda didn’t know at the time that the officer was wrong. And she didn’t know then that thousands of Indigenous women go missing and are murdered at disproportionately high rates compared with other ethnic groups. The FBI’s National Crime Information Center reported 5,203 missing Indigenous girls and women in 2021, disappearing at a rate equal to more than two and a half times their estimated share of the U.S. population. The real rate is likely higher; the total was deemed an undercount in an October report to Congress because of a lack of comprehensive federal data.

Nobody knows how many missing or murdered Indigenous women there are, but it’s enough to have its own acronym: MMIW. Enough for President Joe Biden to describe it as an “epidemic” and for Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland to label it a crisis while calling for more federal action.

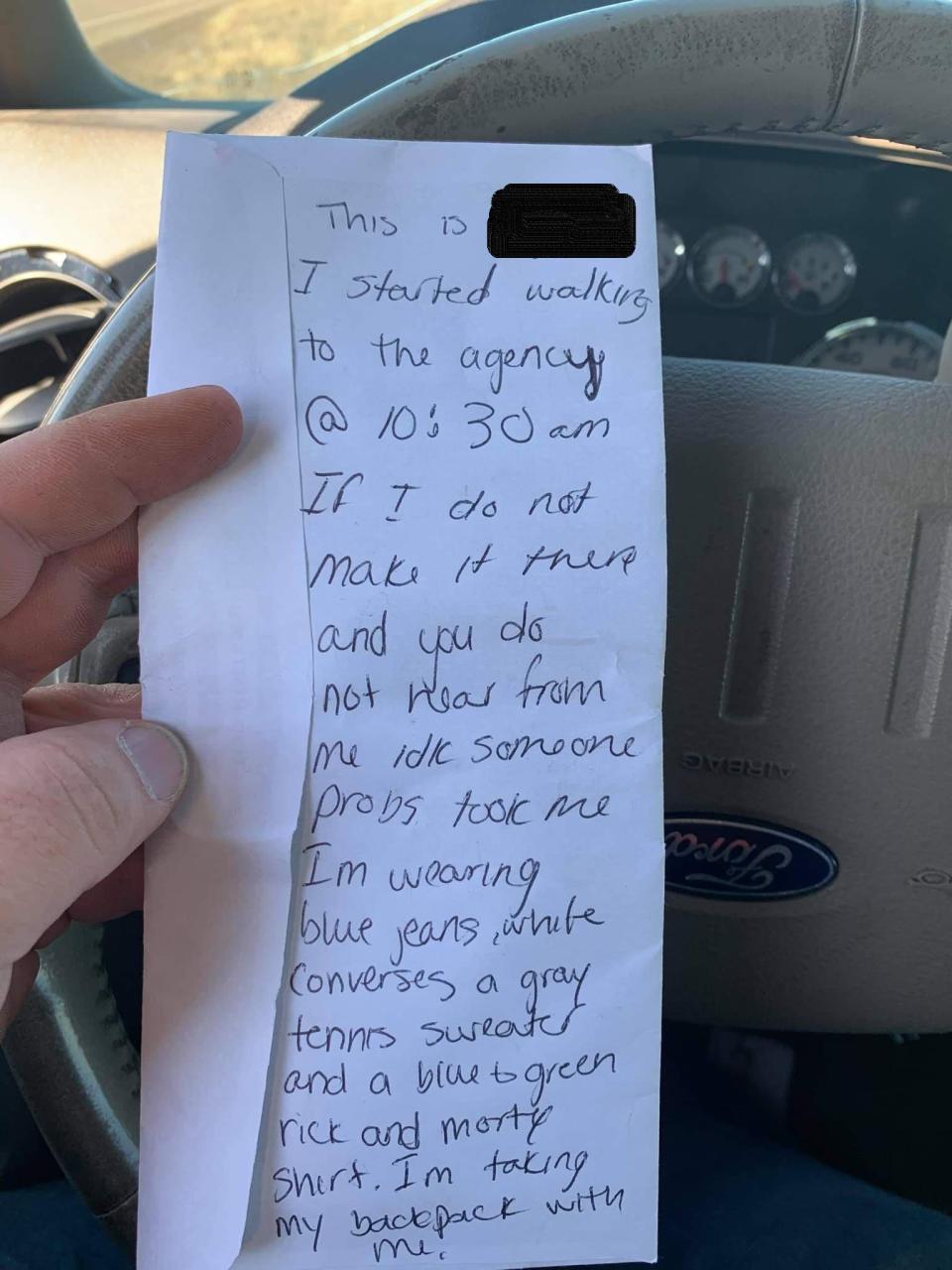

Enough for a Native woman to take to social media last year to share how her teenage niece, alone after her car broke down on a desolate Montana road, left a scribbled note on the back of an envelope. It provided her name, a description of what she wore and the time she’d left on foot to seek help. “If I do not make it there and you do not hear from me idk (I don’t know) someone probs took me,” she wrote.

Enough for Native mothers and grandmothers to impress upon their daughters the need to be vigilant.

“It’s terrifying to me,” Susan Bliler, a member of the Assiniboine and Gros Ventre tribes in Montana, told the USA TODAY Network in explaining why she took her teenage daughter to a boxing club to learn how to defend herself.

“One day she told me, ‘I don’t want to fight.’ And I just said, ‘You don’t have to fight, but I want you to know how to fight in case something happens. You need to know. You just have to. Something could happen to you.’”

Cheryl Horn, a resident of the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation in Montana, spoke about the lessons her granddaughter and friends had absorbed by an early age.

“She sells keychains with whistles and pepper spray for self-defense,” Horn said. “She and her 11-year-old friends took those keychains when they went to a Walmart in Billings. They're very, very aware of the dangers that face them.”

In seeking explanations for the problem, activists for missing or murdered Indigenous women point to centuries of colonial trauma and prejudicial or ineffective government policies. These entrenched within Indigenous communities higher rates of poverty, substance and domestic abuse, and other social ills that contribute to Indigenous women having a lower life expectancy rate than other groups.

Those same factors can also affect the urgency with which cases are handled. Time and again worried loved ones have said their concerns were dismissed by police too busy to search for “another drunk Indian.”

A historical distrust of police doesn’t make it any easier to solve cases that may not even be reported. Nor does chronic underfunding for tribal police forces or a quagmire of conflicting jurisdictions for agencies responding to calls in and around tribal lands.

Malinda didn’t know any of that at the time she spoke to the officer at the Cheyenne Depot. The biggest concern she’d had with Hanna came a few months earlier when Malinda had urged her daughter to leave what she said was an unhealthy relationship with Jeremiah’s father.

Growing up on “the rez,” Malinda had always felt safe. It was the kind of place where she could leave her keys in the car and her door unlocked without concern. Now, she felt certain that something was wrong.

So she ignored the officer’s advice and began asking questions herself, on Facebook and of the customers who came to the store, a popular gathering point in Lame Deer, a tight-knit community of fewer than 2,000.

Has anyone seen Hanna? When did you see her last? Who was she with?

She turned again to Facebook to seek breastfeeding mothers willing to feed Jeremiah. Three women responded. Tips from her other questions started rolling in. The next day, she filed a missing person report despite what she’d been told. Yet she didn’t stop her own inquiries.

Over the next few days, Malinda, who was 43 at the time, drove to nearby towns asking people if they’d seen Hanna. She helped organize three searches. She obtained security camera footage from two places where people said Hanna had been. She even drove a suspect to the police station for an interview with investigators.

“We took on the role of being the investigating police officer,” she said, crediting the dozens of community members who turned out to scour the banks of a creek and surrounding hills where Hanna’s car had been found.

Malinda and her friends were determined to undertake the investigation themselves — for good and for bad — until she had the answers she needed.

Even if they weren’t the answers she wanted.

No waiting period for missing person report

Malinda had been told wrong. Bureau of Indian Affairs protocols for cases involving a missing Indigenous woman inside Indian Country say officers should accept a missing persons report at any time, regardless of whether the woman has been missing for only a short time. BIA officials did not respond to requests for interviews about the incident nine years ago.

In the first 24 hours that a person is missing, there should be a “flurry of police activity,” said Bryanna Fox, an associate criminology professor at the University of South Florida and a former FBI special agent.

“Within 48 hours, (the missing person) may not even be in the country anymore,” Fox said. “Or the opposite, they might not even be alive anymore.”

Even if Malinda had gotten immediate assistance, she faced a quandary unlike any other in American law enforcement. Crimes that occur on or near a reservation are subject to a patchwork of laws establishing criminal jurisdiction among federal, state and tribal law enforcement agencies. Who’s in charge of an investigation depends on the severity and location of the crime, and even whether victims or perpetrators are Native.

In Montana, generally, the investigation into a murder of a Native woman by a Native man on tribal lands falls to the FBI and the Bureau of Indian Affairs or tribal police. If the accused is a non-Native, federal law enforcement alone would have jurisdiction. If the crime occurred off the reservation, responsibility would likely fall to a county sheriff’s department.

As if that weren’t confusing enough, jurisdiction on tribal lands isn’t the same in every state or reservation. The knot of policies becomes even harder to untangle when the location of the crime is uncertain or the identity of the perpetrator is unknown.

When Malinda filed the missing person report for Hanna, neither she nor the authorities could know yet who would ultimately be responsible for investigating the case. That can lead to something like a never-ending round of pass the buck, explained Monte Mills, professor and co-director of an Indian law clinic at the University of Montana.

“So what happens at the beginning of these cases,” Mills said, “you have law enforcement agencies saying, ‘Well, that’s not our responsibility. We don’t have jurisdiction. So call the sheriff.’ And then they call the sheriff and the sheriff says, ‘Well, that’s not our responsibility. Call the Bureau of Indian Affairs.’ And they call the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and they say, ‘Well, that’s not our responsibility. Call the FBI.’ The FBI says, ‘That’s not our responsibility. Call the tribe.’”

The laws also challenge investigators, who can be stymied by limits on whom they can question and where. And while jurisdictional issues can crop up in cases anywhere city borders abut, tribal cases are complicated by vast spaces patrolled by understaffed agencies.

Annita Lucchesi – founder and executive director of Sovereign Bodies Institute, an organization that collects and analyzes data on missing or murdered Indigenous women – said the system doesn’t work because it was never designed to protect Native people in the first place.

“It doesn’t reflect our value systems, it does not create a safe environment for Native victims of violence to come forward, and it does nothing to address the roots of violence in Indigenous communities,” said Lucchesi, who is of Cheyenne descent. “So it’s a system that’s pretty useless in terms of addressing crises like missing and murdered Indigenous people or gender and sexual violence in our communities.”

‘I was just looking for my daughter’

When Hanna was still missing on July 5, the day of her sister Rosie’s wedding reception, Rosie pushed her mother to file the missing person report. Again, Malinda said she was brushed off by officers. Although they took the report, they told her they were busy because of the holiday weekend and told her Hanna was probably drinking with friends and scared to come home. They told Malinda to come back Monday if Hanna still hadn’t returned, she said.

“These police are here to protect and serve, but who are they protecting?” Malinda recalled thinking at the time. “Who are they serving? It sure isn’t my family.”

Her own investigative efforts had started producing results. A customer at the Cheyenne Depot told her about seeing Hanna’s car at Muddy Creek. She used Facebook — extremely popular in a remote region where cell service is spotty and messages can be sent on a low bandwidth — to call for volunteers to search the area the next day.

Dozens of people showed up. The volunteers joined her in walking along both sides of Muddy Creek for miles, but they found nothing. Malinda’s attention turned to a new tip.

People on Facebook had messaged her that Hanna had been seen at the fireworks July 3 with Gina Rowland and Garrett Wadda. Both were about 40 at the time, and Hanna had gone to school with the couple’s children. Malinda spotted Rowland’s car outside the Lame Deer Trading Post IGA grocery store.

By this time, word had spread about Hanna being with the couple. Some of the people who’d helped with the search confronted Rowland, demanding answers. Malinda convinced the woman to help by telling police what she knew. She drove Rowland to the Bureau of Indian Affairs police station herself.

According to police reports obtained by the USA TODAY Network, officers said they learned through a series of interviews with Rowland and Wadda that the couple had been drinking with Hanna the night of the fireworks. The three of them went to the Jimtown Bar & Casino, just outside the reservation, which is dry. Later, they stopped at the Cheyenne Depot and finally at the home of Wadda’s aunt, who lived on Muddy Creek Road outside of Lame Deer. The couple told officers they didn’t know what happened to Hanna after they went to bed.

Malinda remembers Rowland’s interview with police that day being brief. Afterward, at her urging, tribal officers went to look at Hanna’s car. Malinda followed them, Rowland riding in the back seat, cooing over Jeremiah. Biting back her anger, Malinda noticed a cut on the other woman’s hand.

The search of Hanna’s car didn't turn up anything.

On July 7, Malinda and more volunteers searched the hills near Muddy Creek. When Rowland and Wadda came to help, Malinda told them to leave. That search also proved fruitless.

Next, Malinda drove to the bar where Hanna had been seen July 3. She asked to see security camera footage. She also obtained footage from the convenience store. One video showed Hanna with Rowland and Wadda buying alcohol and leaving together. In the other, Hanna paid for gas before returning to her car, with Rowland in the passenger seat and Wadda in back. Malinda felt no closer to solving the mystery, despite all her efforts.

“I always think that was the police’s job, but when a mother loses her daughter, it’s natural instinct to do whatever you have to do to find her,” Malinda said. “I really didn’t know I was doing the police’s job; I was just looking for my daughter.”

By July 8, five days after Hanna was last seen, tribal officers had notified the FBI of the case, as is customary when it’s believed a major crime against a Native person in Indian Country has occurred. Following a new tip, another search was planned at the Lame Deer rodeo grounds, this one involving the investigators and volunteers. But after a storm rolled in, officials called off the search, though some of the volunteers remained behind.

Investigators asked Malinda to identify a Nike shoe that had been found, but she couldn’t bring herself to do it. Hanna’s sister Rosie had to go look at it.

There was no mistaking the black and white high-top basketball shoe. It was Hanna’s.

‘Stripped of authority to protect their people’

With an estimated 70% of Indigenous people in the U.S. living off reservations, the confusion over jurisdictions is only a contributing factor to the problem of missing and murdered Indigenous women. Activists for missing and murdered Indigenous women, in addition to many scholars, say it’s impossible to separate the problem from centuries of suffering inflicted by the settlement of North America.

Native tribes were decimated by diseases introduced by colonizers and impoverished by policies that interned them onto reservations. Later, children were shipped to boarding schools and forced to abandon their language and culture. In the 1950s, a federal relocation program encouraged Native Americans to leave reservations for cities, while simultaneously trying to terminate recognition of tribes, with pledges of support that, like previous promises, weren’t fulfilled.

The consequences of generational poverty and all its trappings can be gleaned from a consultant’s report on policing in the Navajo Nation, the largest of the 574 federally recognized Indian nations in the U.S. About 40% of people living on the reservation that covers parts of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah don’t have running water in their homes, the report notes; about 15,000 don’t have electricity.

The report connects poverty to “the effects of colonialism,” which it says “are still experienced as drivers of critical problems in the Navajo Nation. Today, gender violence, alcohol and drug abuse, inadequate housing, needs of the mentally ill, availability of firearms, drive demand on the police.”

The same conditions apply on many, if not most, tribal lands along with Indigenous communities far removed from reservations, activists say. They lay at the root of the crisis by exposing Indigenous women to disproportionate levels of violence, including domestic abuse and human trafficking. For example:

Figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show homicide was the third-leading cause of death between 1999 and 2019 among Indigenous females age 1-34 — even more than cancer, which was the third-leading cause of death among females of all races in that age range. (The two leading causes for both groups were unintentional injury and suicide.)

A 2016 study prepared for the National Institute of Justice showed that 4 in 5 Indigenous women report having experienced violence in their lifetime. The numbers, drawn from a National Intimate Violence Survey, also showed that Indigenous women were 2.7 times more likely than white women to have experienced sexual violence in the previous year.

In Montana, Native Americans account for 6.7% of the state’s population, yet they comprise, on average, 26% of its active missing persons cases. Such disparities are common in western states with larger Indigenous populations.

The poverty and violence among Indigenous communities both on and off reservations affect how Natives are treated by law enforcement, said Lucchesi of the Sovereign Bodies Institute.

“They love the idea of Native communities that are chaotic and ungovernable,” she said, because it validates a racist narrative that Native people can’t govern themselves and maintain peace when “all you do is run around and drink and kill each other.”

“It’s not just about seeing Native on Native crime as insignificant or not their problem,” she said, adding, “It legitimizes their ongoing occupation of our lands and our peoples.”

Mary Kathryn Nagle, a lawyer who specializes in tribal law and represents Indigenous families pro bono in missing cases across the country, said her efforts to collect evidence, transcribe interviews with suspects and encourage investigators to interview witnesses in cases of missing or murdered Indigenous women are often ignored.

“They can ignore these cases because what’s the consequence of ignoring the death of a Native woman? What happens to you?” she said. “I haven’t seen a single person face any consequences for ignoring a homicide of a Native woman or girl.”

For more than a hundred years, tribal communities have sought to restore their autonomy over crimes committed on their lands; in the view of many Native advocates, the missing and murdered Indigenous women movement is an indication that more progress is needed.

Judge BJ Jones, executive director of the Tribal Judicial Institute at the University of North Dakota, said it’s unfair to blame tribal police forces when they lack the authority to do more in some cases and often lack the funding to do the job that’s expected of them.

“There’s simply never been an investment in enough officers, enough detectives, enough justice personnel to really deal with (some) crimes,” he said, adding, “I think that’s why people talk about this jurisdictional quagmire in Indian Country, because tribes have really been stripped of their authority to protect their own territory and their own people by Congress.”

Mills, the co-director of an Indian law clinic at the University of Montana, agreed: “Empowering tribal governments and empowering tribes themselves to exercise authority to protect their communities – that seems like both a simple and effective approach.”

At the very least, funding to improve staffing levels and training for tribal police would help make those communities safer. While the federal government has treaty responsibilities to keep tribal members safe, tribal law enforcement entities, which are overseen by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, are severely understaffed and under-resourced.

The Navajo Nation police department, for example, had 158 patrol officers for an area spanning 27,000 square miles when a consultant concluded in 2020 the department needed 300 patrol officers to adequately protect an area larger than 10 of the 50 U.S. states.

On Montana’s Crow Reservation, five tribal police officers patrol an area of nearly 3,600 square miles – bigger than Rhode Island and Delaware combined.

“Anywhere else in the country outside of Indian Country, you make a phone call to police, you get a five to 10-minute response,” said Frank White Clay, chairman of the Crow Nation. “In Indian Country, it’s five to 10 hours. Or weeks.”

New federal laws and actions have attempted to address the problem.

Savanna’s Act – named for Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind, who was killed in 2017 in North Dakota – requires the Department of Justice to enhance training, coordination and data collection in cases involving missing and murdered Indigenous women. The Not Invisible Act aims to increase intergovernmental coordination. In 2019, President Donald Trump created Operation Lady Justice, a presidential task force dedicated to missing and murdered Indigenous people.

But experts, advocates and family members say these initiatives don’t go far enough. And though the laws are on the books, an October report from the General Accounting Office noted how federal officials failed to meet deadlines imposed by the new laws for things like public education on data gathering, outreach to tribal stakeholders and the development of guidelines for responding to such cases.

“That really shows their level of investment,” said Abigail Echo-Hawk, director of the Seattle-based Urban Indian Health Institute. “It’s not only disappointing but I don’t think that would happen if this was a community of white women.”

In 2016, the Urban Indian Health Institute surveyed 71 urban cities across the country to provide a snapshot of the problem because they knew the federal numbers weren’t capturing the full picture.

“The biggest issue is racial misidentification or not collecting ethnicity,” Echo-Hawk said. She told the story of a missing woman in Washington state who’d been misclassified after investigators looked at a picture and guessed.

“I wish that was an uncommon story, but it’s not,” she said, explaining her advocacy for police training on racial identity. “They don’t see it as an issue. In fact, it’s so integral for us to understand the scope of the problem.”

Other federal action includes Biden’s $1.2 trillion infrastructure plan signed into law in November. Among its $13 billion outlay for Indigenous communities were $6 billion to support water infrastructure in tribal communities; about $4 billion for roads and bridges; and $2 billion for expanding broadband access, among other measures.

Indigenous activists also were encouraged by Biden’s appointment of Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna and first Native American to oversee the Interior Department, which includes the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The former New Mexico congresswoman has spoken passionately about missing and murdered Indigenous women. When she announced in April 2021 the creation of a unit to investigate such cases and coordinate resources among federal agencies and Indian Country, supporters hoped it signaled real progress rather than just more bureaucratic maneuvering.

Seeking an update, the USA TODAY Network tried for weeks to secure an interview with Haaland. In an October Q&A with the Washington Post, she had this to say about the unit’s progress:

“The new Missing & Murdered Unit is providing leadership and direction for cross-departmental and interagency work involving missing and murdered American Indians and Alaska Natives. The Office of Justice Services recently selected and on-boarded senior positions that are responsible for stakeholder collaboration, continued policy development, overall performance of the unit and direct oversight of field investigations. In addition to building out its personnel, the Department is focused on increasing its infrastructure capacity, and has opened two additional investigative offices dedicated to reviewing unsolved cases in Muskogee, Okla., and Vancouver, Wash.”

‘We did the best we could’

The night of July 8, Malinda gathered her extended family for a “callback ceremony.” They laid out Hanna’s clothes on the floor, singing and praying to return her spirit to her body.

A knock on the door interrupted the ceremony; an officer wanted to know if Hanna had any tattoos. Malinda told him she had two stars and her Indian name – Amesekehae, or “Pemmican woman,” which had been passed through her family for generations – on her back and shoulders. The officer left.

Malinda told herself the question meant nothing, just an investigator being as thorough as she had been. “I always thought she was alive somewhere,” she recalled. “I flatly refused to believe that she was deceased. You know, it’s a mother’s worst nightmare. I wouldn’t let myself believe that.”

After midnight, another officer came to the house. Malinda doesn’t remember much of what he told her. According to police reports, Hanna’s body was found at the rodeo grounds in Lame Deer positioned face down, her pants unzipped, her underwear pushed down and her shirt and bra pushed up. Her body was too badly decomposed to determine whether a sexual assault had occurred or what caused her death.

No arrests were made. Rowland and Wadda had left Montana for the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming. In the end, the case was solved not by investigative work but by a drunken confession. In January 2014, six months after Hanna’s disappearance, Rowland went drinking with her former sister-in-law and told her what happened. That woman called the FBI, and Malinda soon got word that Rowland and Wadda had been arrested on murder charges.

“It was probably one of the happiest, happy-sad, days of my life,” Malinda recalled.

Police reports spelled out what Rowland told her sister-in-law. She and Wadda had been drinking with Hanna that night in a trailer. Rowland said she woke up to screaming and found Wadda forcing himself on Hanna while she screamed that she was being raped. Rowland said Hanna hit her when she tried to help. Rowland and Wadda beat Hanna until she was unconscious. Rowland dragged Hanna’s body outside and Wadda drove her to the rodeo grounds.

In October 2014, Rowland pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and was sentenced to 22 years in prison. Authorities told Malinda they had insufficient evidence to prove the rape that Rowland alleged. Wadda pleaded guilty to accessory after the fact, admitting he moved Hanna’s body. He was sentenced in 2015 to 10 years in prison. He was released from federal prison in January. Malinda said he’s back in Lame Deer. People send her photos when they see him. She wishes they wouldn’t.

“There was no evidence, so it was her word against his,” Malinda said. “When we were doing our own search, we literally lost a lot of evidence because we weren’t professionals. We didn’t know what we were doing. … We lost a lot of forensic evidence, fingerprints, shoe prints, stuff like that.”

She finds solace in knowing that among the thousands of missing and murdered Indigenous women tracked by groups like Sovereign Bodies, Hanna’s case is unusual because the perpetrators were convicted and it led to change and greater awareness of the problem.

In May 2019, then-Montana Gov. Steve Bullock signed Hanna’s Act. The law authorized the state Department of Justice to assist in all missing persons cases and created a missing persons specialist.

Hanna’s birthday, May 5, is now a national day of awareness for missing and murdered Indigenous people. Every year on her daughter’s birthday, Malinda travels to Montana’s capital in Helena to join other family members of missing or murdered Indigenous people in advocating for better communication among law enforcement agencies and more resources for tribal police to boost staffing and improve low retention rates.

“I finally had my closure,” Malinda said.

Hanna’s grave sits on a hill near her mother’s house. Her tombstone is dark gray and shaped like a big heart. Jeremiah, her son, is now a slender and shy 9-year-old. Both his ears are pierced, he’s missing some baby teeth, and his mother’s tombstone reaches to just below his bony shoulders. His laugh reminds Malinda of Hanna, but his growth remains a symbol of time passing without her.

While Malinda spoke of his mother on a day last autumn, Jeremiah draped his body over the headstone and traced his small finger in the grooves that spell his mother’s name. Malinda has never hidden the truth from him. Though Jeremiah knows Malinda, now 51, is his grandmother, he calls her Mom.

“I’m the only one he’s ever known,” Malinda said.

She won’t let herself second guess her efforts in the days after Hanna disappeared. She doesn’t wonder if Rowland and Wadda would have faced longer prison sentences if law enforcement had been involved sooner, or if she and the volunteers searching for Hanna had known how to preserve crime scene evidence in their desperation for answers.

She can’t let herself think about those things, telling herself over and over, “We did the best we could with what we had.”

“We just had nothing.”

Contributing: Andrea Ball, USA TODAY; Sarah Volpenhein, USA TODAY Network.

Nora Mabie is a reporter who covers Indigenous communities for The Great Falls Tribune in Montana. She can be reached at nmabie@greatfallstribune.com and on Twitter @noramabie. Derek Catron is a national enterprise editor for USA TODAY. He can be reached at dcatron@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: MMIW day: Why Native American women are victims at higher rates