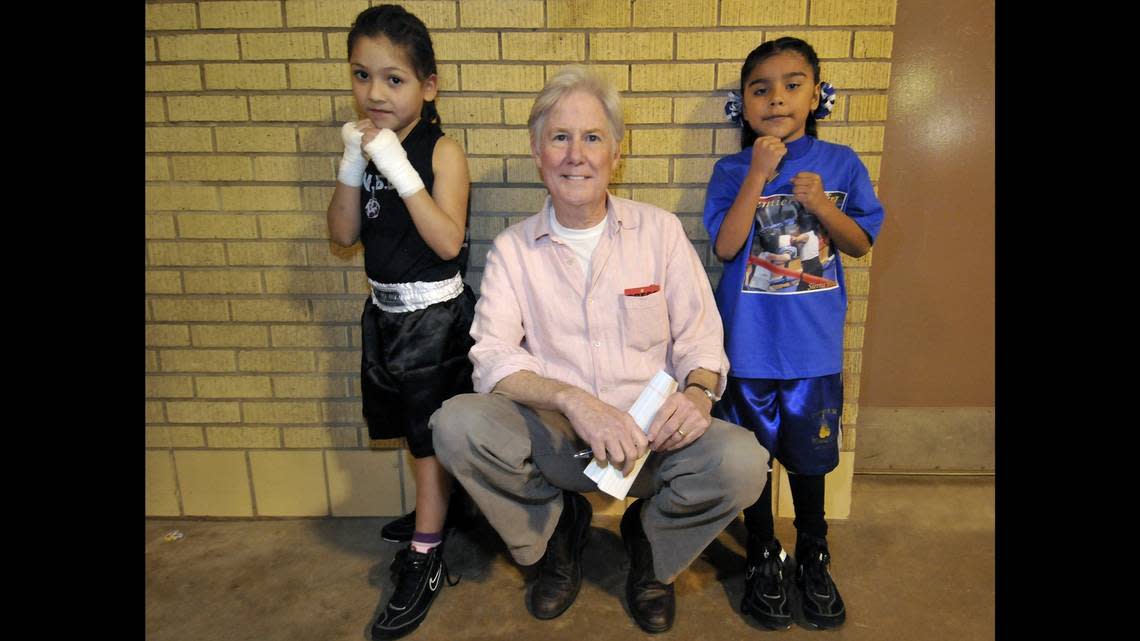

David Casstevens, Fort Worth native who covered Super Bowls and Stock Shows, dies at 77

David Casstevens, a Fort Worth native who told the stories of sports superstars, peanut vendors and little-leaguers in a 40-year newspaper career, has died. He was 77.

Friends and family remembered Casstevens for his kindness, his quiet demeanor and his ability to center humanity in each of his stories.

“He was a Fort Worth guy through and through,” said Randy Galloway, a fellow sports columnist and friend who worked with Casstevens at the Dallas Morning News and the Star-Telegram.

Born in 1946, Casstevens graduated from Paschal High School in 1964 before earning his degree in journalism from the University of Texas at Austin in 1969.

He had brief stints at newspapers in Abilene and Waco before joining the Houston Post in 1972 to cover the Houston Oilers.

Casstevens returned to the Metroplex in 1980 to work for the Dallas Morning News, where he became part of a triumvirate of sports columnists that included Galloway and the legendary Blackie Sherrod.

He moved to Phoenix in 1990 to work as a columnist and sports editor for the Arizona Republic before returning to Fort Worth in 2002 to write feature stories for the Star-Telegram. He retired in 2011.

He saw his role as a sports columnist to offer insight while not stoking controversy for controversy’s sake, according to an advertisement announcing his hiring at the Arizona Republic in September 1990.

“He wasn’t a shock jock columnist,” said fellow sports columnist Paola Boivin, who worked with Casstevens at the Arizona Republic. He had a quiet kindness that made it easier for professional athletes to trust him, she said.

Casstevens liked covering events like the Stock Show so much that friends would joke about him running away to join the carnival, said Art Chapman, a friend and Star-Telegram colleague.

He also took it upon himself to cover the Fort Worth Westside All Stars’ Little League World Series run in 2002.

He wrote stories about the dreams of the individual players, a parent struggling with cancer, and a coach using whimsical song lyrics to keep the kids loose during the games.

“That’s a story that a lot of people wouldn’t have wanted to do because it wasn’t high profile, but he enjoyed doing that sort of thing,” Chapman said.

He was good at focusing on humanity, because the story for him was always a story about people, his wife Susie said. He would write about the peanut vendor or a player’s family member when covering a sporting event, she said.

She recalled a profile of Houston Oilers running back Earl Campbell in which Casstevens described Campbell’s motivation to lift his family out of poverty.

“He would write about people in terrible circumstances, but the way he would write about it was beautiful. He made life seem beautiful,” she said.

He had a lyrical style to his writing that went beyond the events of whatever game he was covering. After the Oakland Raiders beat Houston 34-0 in 1972, Casstevens called the Oilers the “greatest aid to sleep since darkness.”

In a profile of the northeast Texas town of Pittsburg before the 2011 Super Bowl between the Pittsburgh Steelers and Green Bay Packers at AT&T Stadium, he described residents’ lack of enthusiasm by saying “folks must be taking a lot of aspirin” to treat their Super Bowl fever.

Even after getting sick with COVID-19, Casstevens continued to write stories about his 93-year-old Fort Worth house, Susie said.

“He would write about the house like she was a woman, and tell stories about what happened in each room,” she said.

Friends remembered Casstevens’ kindness. They said he was always willing to help fellow reporters and refrained from criticizing colleagues.

“He treated people the right way,” Galloway said. “You never heard a negative word about him.”

The only exception to this rule was during late night football and baseball games when Casstevens was up against a deadline, Galloway said.

“He was a slow writer, and he sweated over every word,” Galloway said.

Part of that was because he cared so much about the craft of his writing, Boivin said.

“He would agonize over it because it was important to him,” she said.

Casstevens is survived by his wife, Susie, three children, four stepchildren, two grandchildren, seven step-grandchildren, and his brother Mark.

A memorial service is scheduled for 11 a.m. Feb. 2 at Broadway Baptist Church, 305 W Broadway Ave., Fort Worth.