S. David Freeman, public power chief and energy advisor, dies at 94

S. David Freeman, who steered the nation’s largest public electric utilities with a commanding and at times uncompromising vision and was an early advocate of renewable energy, has died.

Freeman died Tuesday at a hospital in the Washington, D.C., suburbs after suffering a heart attack, his daughter Anita Hopkins said. He was 94.

As president of the Los Angeles Board of Harbor Commissioners, Freeman oversaw a push in the 2000s to clean up the air in the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Industry executives and labor groups fiercely contested aspects of the plan, saying they would drive down profits and eliminate jobs,

But Freeman “was a steamroller," recalled Jerilyn López Mendoza, who served with him on the commission. "He would charm you, talk circles around you, until he had you convinced his way was the right way.”

After leading the port commission, Freeman served as then-L.A. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa’s deputy mayor for energy and the environment. In an interview Wednesday, Villaraigosa, who met Freeman as a state assemblyman while drafting air quality legislation that created the Carl Moyer Program, called him "a force of nature."

"Public service was in his bones, in his DNA," Villaraigosa said. "He's given people ideas that made them millions, and he didn't care. He just wanted to change the world, and he did."

Freeman was not without detractors. When Gov. Gray Davis nominated him to lead the state power authority, Republican lawmakers assailed his tenure at the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, saying he had ripped off ratepayers during the 2000-01 energy crisis, brought on by a disastrous deregulation of the state's power market. Electricity costs rocketed, and power outages rolled across the state as a result of the crunch.

V. John White, a clean-energy advocate, clashed with Freeman over what he called the “gun to the head” contracts Freeman signed for electricity for California during the crisis. “He signed $40 billion worth of contracts in 30 days, and on the whole, I told Dave we kind of got rolled,” White said. “And he completely defended them and said: You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Over his seven decades shaping energy policy and leading local and state power authorities, Freeman would embrace cleaner, renewable sources of energy.

Freeman told the historian Harry Kreisler that he remained "pretty conventional about nuclear power and the whole power business" until the day two women from New Hampshire came to his office in the White House. There were plans to build a nuclear power plant near their homes, they told him, but they had done some research and figured that if people in their area simply conserved energy, there was no need for nuclear power.

"I listened to them, and I checked it out, and they were right," Freeman recalled. "All of a sudden, it was like a light bulb went off in my head that we were just wasting a tremendous amount of electricity, and we didn't need to build as many plants as we thought we needed to build, because it's cheaper to conserve."

The son of an umbrella repairman, Freeman was born Jan. 14, 1926, in Chattanooga, Tenn. A high school teacher took a look at his math scores and told him to study engineering, his son Stanley said, and so Freeman enrolled at Georgia Tech. He took a job after graduation with the Tennessee Valley Authority, the sprawling federal corporation established during President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal.

But Freeman was less interested in engineering than policy and advocacy, his son said, and after five years of designing power plants and hydroelectric stations, he enrolled in the University of Tennessee's law school. After earning a law degree, he returned to the TVA as an attorney.

Freeman followed his boss, the general counsel of the TVA, to the nation's capital, where over the next two decades he advised Presidents Johnson, Nixon and Carter and the Senate Commerce Committee on energy policy. At the request of President Carter, Freeman returned to Tennessee in 1977 to lead the TVA.

The move began a roving, three-decade tour that took him through Texas, New York, Sacramento and Los Angeles and to the top ranks of the nation’s three largest public utilities — the TVA, the New York Power Authority and the Los Angeles DWP, which he led from 1997 to 2001.

“He believed in institutions,” said White, who met Freeman when Freeman took over the Sacramento Municipal Utilities District in 1990 and guided it through the closure of a nuclear plant. “That was his whole mind-set: Public power was the place to be.”

Freeman steered those institutions toward his vision, often without compromise or patience for opposing points of view, López Mendoza said.

Freeman remained fiery into his 10th decade, White said, recalling Freeman's 90th birthday party in Sacramento. After the party, he insisted on attending a board meeting of the Sacramento Municipal Utilities District, the utility he had led two decades earlier. White said Freeman stood up and told the utility’s directors: “You ain’t doing enough, and you’re resting on your laurels!”

A week after his 93rd birthday, Freeman flew from his Washington, D.C.-area home to Los Angeles, where he urged Mayor Eric Garcetti’s appointees to the DWP Board of Commissioners to abandon plans to invest billions of dollars in three coastal gas plants. Committing that much money to fossil fuels would make the board members “intelligent deniers” of climate change, Freeman insisted.

“I know you’re not. I know you’ll do the right thing,” he told them. A few weeks later, Garcetti changed course and promised to shut down the gas plants.

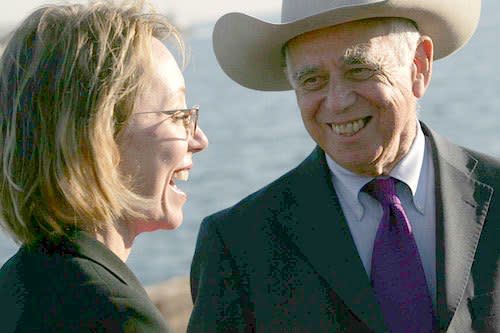

In his later years, Freeman became known as the “Green Cowboy,” both for his advocacy and his trademark hat. His daughter said he picked up the hat while working for the Lower Colorado River Authority in Austin, Texas, after a dermatologist told Freeman he needed to keep out of the sun. He would wear a cowboy hat until the day, last week, when he was admitted to the hospital, Hopkins said. The hat, a gray one, is still in her home.

Freeman is survived by his daughter, two sons, nine grandchildren and a great-grandson.

Times staff writer Sammy Roth contributed to this report.