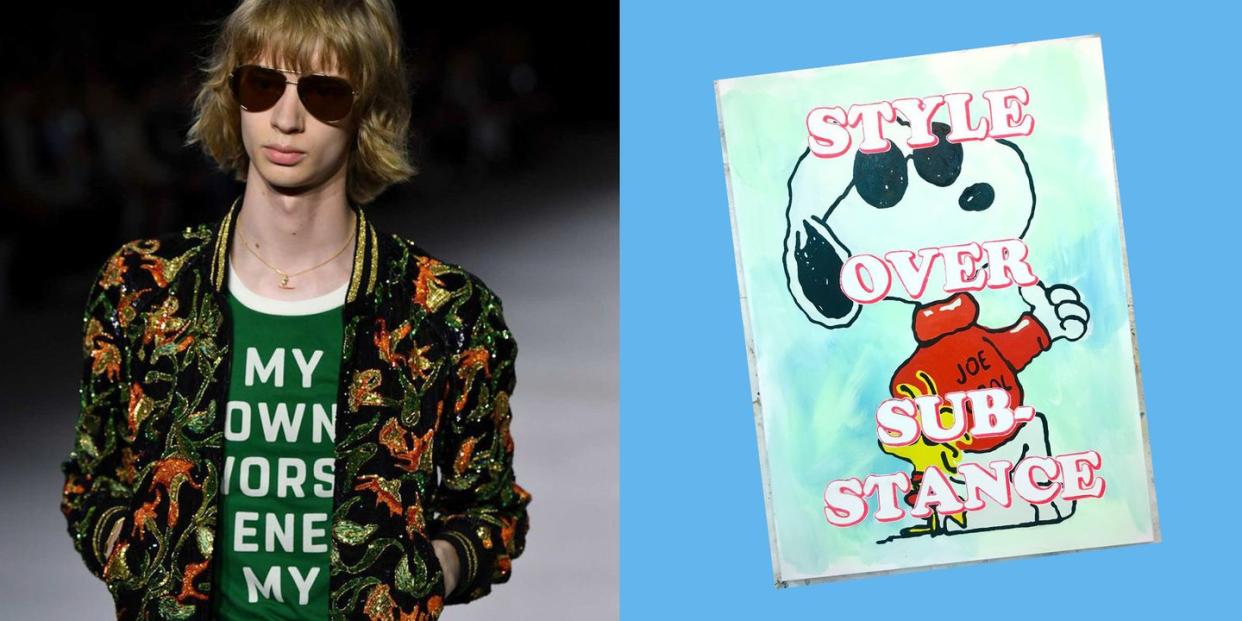

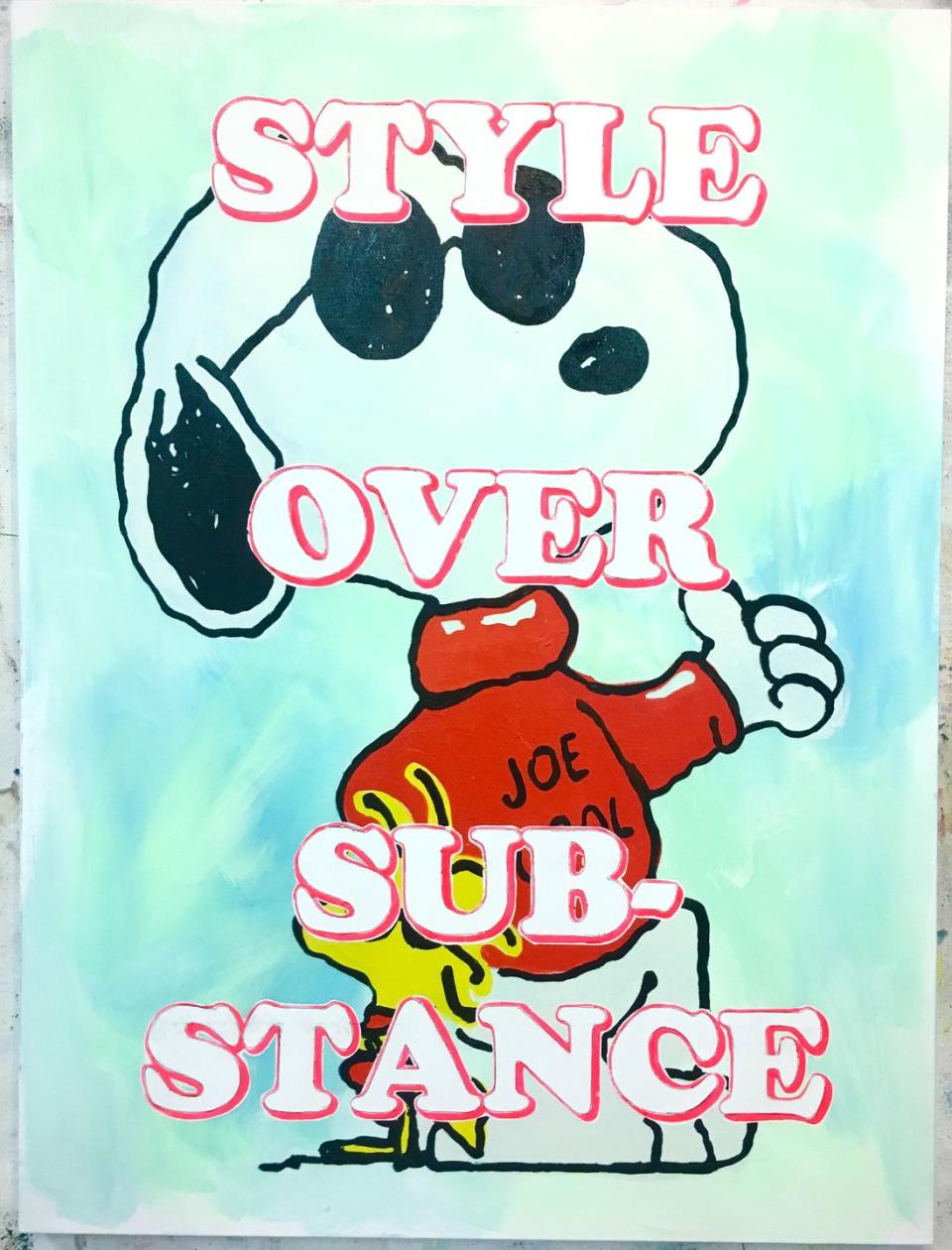

David Kramer Makes Handmade Memes For a Living. Now He's Making Them For Celine.

When the artist David Kramer received an email from Hedi Slimane proposing a collaboration, he initially wrote the email off as spam. Admittedly, Slimane's serious sensibility seems a strange bedfellow for Kramer's poppy, saturated style, which fuses paintings with text in a kitschy send-up of American advertising. Yet for Celine's spring 2020 menswear collection, Kramer and Slimane found common ground in nostalgia, applying a handful of Kramer's iconic phrases (such as "my own worst enemy") to T-shirts and totes in a cheeky, self-referential swipe at the good old days.

Esquire sat down with Kramer to discuss the collaboration process, the deeper meaning behind graphic T-shirts, and the appeal of selling out.

What was Hedi like as a collaborator?

It was a very interesting collaboration because I was taking my own work to this, but I really had never worked in the fashion industry. He really seemed to know exactly what he wanted to do, and he was very sure of himself. I was happy to let him go because of the newness to this. He was very respectful of my work, and I was very happy to see all of the things that he wanted to do. I’ve been working for years in this vein, but to have the opportunity to collaborate with him was like going from playing acoustic guitar to plugging it into electric. It was really a gift.

How did you choose the phrases that made their way into the collection?

At the start of this whole thing, I was approached by him because he had seen my work at the SPRING/BREAK Art Fair over a couple of years, maybe also at Armory, and at a couple of art fairs I participated in. When we first started talking, the first thing I did was ask what he wanted to see. He wanted to see a massive file of things I had done over the years, just to comb through. He came back pretty much right away and had honed it down to what made it into the collection. I was just happy that it was so directed.

Your work often trades in humor and irony, but when we think of Celine and Hedi, they have a more serious sensibility. Did you feel that the collection was able to locate your spirit of humor and irony?

To me, it was very funny in that I definitely see where there’s irony, satire, and self-deprecation. I find it quite funny, really, that there would be this interest in the humor in my work in a fashion line because it seems a bit ironic. The fashion business is not one that really treads in self-deprecation or in humor. Usually it’s very serious, and it takes itself very seriously. I think that had something to do with Hedi’s self-awareness about what he was trying to put forward for this season.

How would you describe that vision?

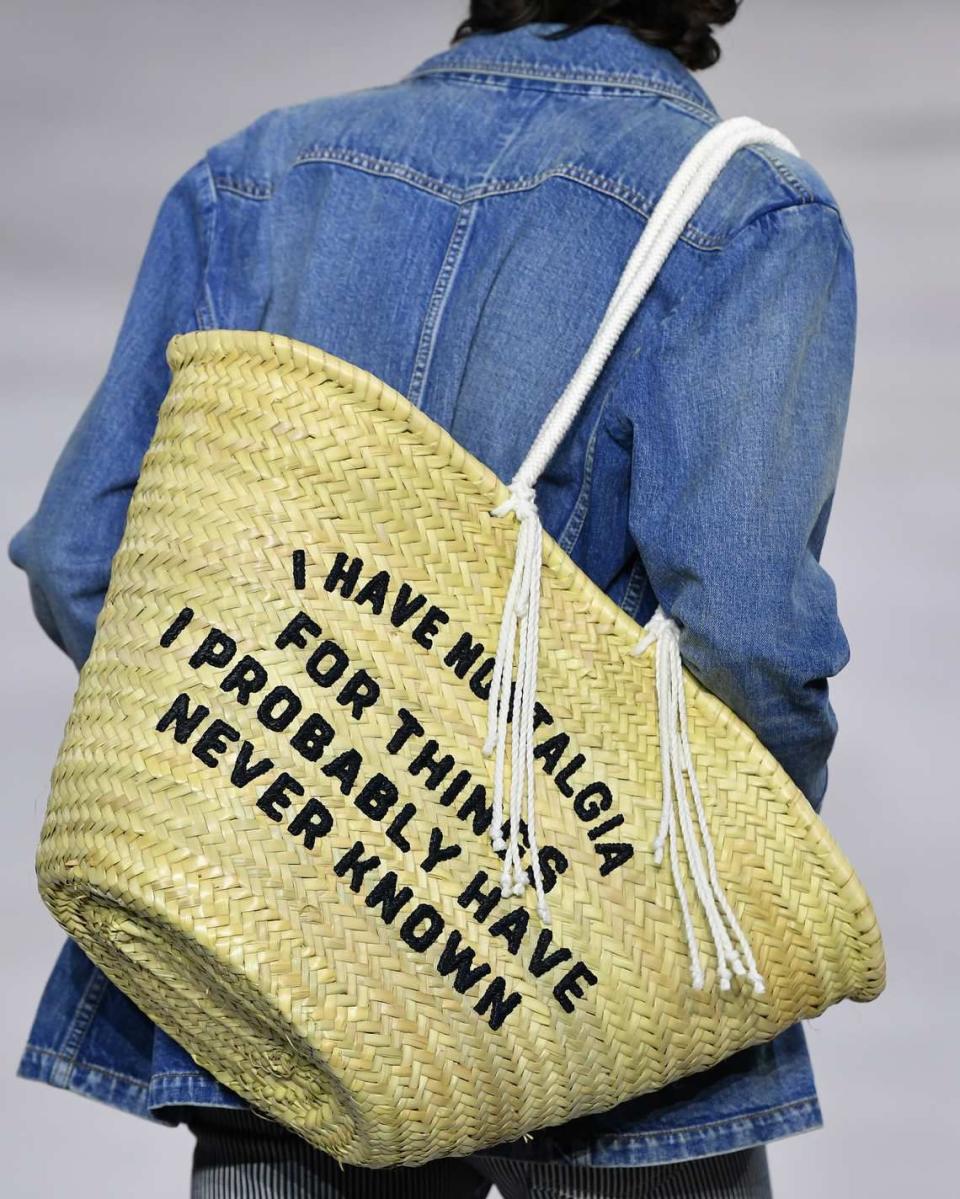

I had been doing a lot of work of late where I was talking about nostalgia. I think Hedi realized that what he wanted was to use the nostalgia. But, for me, the nostalgia is a sort of leaping-off point. One of the sentences we use in the collection is, “I have nostalgia for things that I’ve probably never known.” It’s more of a dream, a desire, or the lack of fulfillment that pushes me. With fashion, there’s a sense of getting what you want out of that world that I am drawn to, but I think that Hedi wanted to talk about nostalgic tropes using vintage ideas. And so, to get ahead of the game, he started to talk about nostalgia in a self-deprecating way.

What was it like to see your work appearing in the same space as Napoleon’s tomb?

I thought that was incredibly funny. I had been to Paris many times, and on my last visit, I went to Napoleon’s tomb. There’s a real ostentatious quality and hubris to the fashion world that doesn’t really makes sense to me, but it makes sense for that context, in a way.

It’s interesting to see the textual element of your work divorced from the visual component. How does the meaning of the text change when it lacks that visual context?

At first, I was a bit wary. When I watched the show and I saw what was presented, I felt a little bit sad. I thought, “Oh, well, that was it. I guess it would be very hard for anyone to identify that as mine because it was taken away from the backgrounds, from the paintings.” But, as it turns out, there has been a lot of attention that has turned onto me from the show. In the run-up to the show, Celine used a lot of my images in the advertisements. The invitations that they had given to people to come to the show were all completely my paintings, with the words and the images together. People who came away from the show who had seen the invitations knew exactly where the context was. I was glad to see it utilized in that way. It’s still my work. I feel satisfied by that, but it was a really interesting thing to watch the show and feel a little bit empty, then be rewarded right afterwards with a lot of attention.

These days, everyone is wearing graphic T-shirts. Why do you think people crave text on their clothing, particularly at this moment in time?

I’m not someone who wears a lot of clothes with words on them. I think this is where Hedi was really quite self-aware. He’s seen, like I have, young people wearing CBGB T-shirts who were perhaps not old enough to go to CBGB when it closed and went out of business. I think he was trying to run ahead of that and point it out: that it is very interesting to see people wearing T-shirts that identify something, even if it doesn’t exist anymore. That’s why I thought it was so great that the text that he chose was very conscious of that. This is a new line of text-based shirts that’s self-aware.

Many of us wear text-based shirts to telegraph something about our identity. It’s a way of presenting ourselves to the world as we’d like to be seen, whether we have much personal investment in what’s on the shirt or not. How do you feel about text on clothing as a statement about identity?

You might wear a Ramones T-shirt, and the Ramones were gone before you even were aware of who the Ramones were. But by wearing a Ramones T-shirt, you tell the world, “This is the kind of music I listen to,” or, “This is the kind of identity that I want to present.” That’s why I think it’s so funny that Hedi really got in on this whole idea, particularly that one line of text about nostalgia, because it really makes sense to me, but not in a way that I would expect from a fashion line. That’s why Hedi is so unique. He’s such a smart designer.

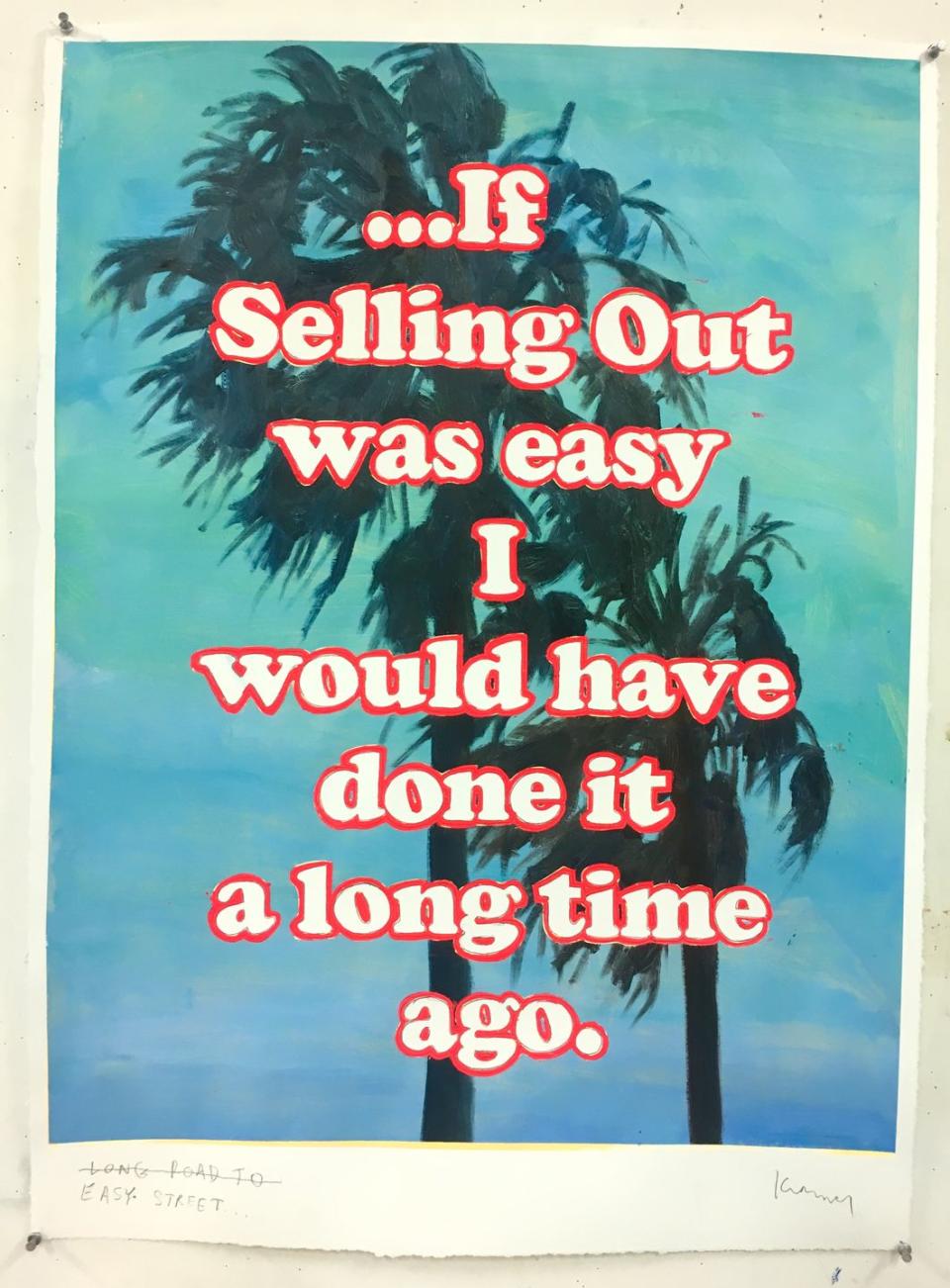

Fashion of course has artistic impulses, but it also has commercial incentives. There’s a loud school of people who think that art should be divorced from commercial incentives, and that it should lack a profit motive. What are your thoughts on your art being brought into a space that’s as much about aesthetic impulses as it is about selling something?

I once did a painting that said, “Art and money should never have anything to do with each other,” and for me that’s usually the case. I’ve also done a painting that said, “If selling out was easy, I would have done it a long time ago.” I find it very strange and funny, but at the same time, I really like it because the art world is its own little vacuum. The fashion world is maybe a vacuum, but it certainly entertains the rest of the world—right away, in fact, as soon as it hits the stores. It’s really interesting to see Jean-Michel Basquiat T-shirts, because his work was not necessarily something that I would have expected to become popular on T-shirts. Now you see these sloppily-drawn crowns on shirts. He was a great artist, and now, I think people still know of this work in this day and age—especially younger people—who didn’t even know he was a painter. I find that exciting.

That’s very true. It’s a way to import their work out of the museum too and place it in a space accessible to people who otherwise wouldn’t encounter it.

Exactly. Some people don’t know that Keith Haring was a painter. They think of him as a graphic artist or a T-shirt designer. I don’t think that he ever was really in the T-shirt business in his life; I think that came about afterwards. He was certainly making posters, doing graffiti, and doing swimming pools. But it’s fascinating and exciting to see him in a new context.

How have social media and the rise of digital culture transformed your process, if at all? In a way, you’re making analog memes.

I joke that I make handmade memes. In reality, I’ve been making text-based paintings and drawings for years before computers. I was really always into text. I don’t like to think about myself as a text-based artist so much as a storyteller. I become more reductive with what I write on canvas, and it translates well on social media. It’s a fascinating thing for me to be able to make a painting, look at it, and think it’s finished, then to post it on social media and see a response to it. The problem with being an artist is that a lot of what you do is a lonely business. You’re standing in a room by yourself, working on something that you are looking at from just a few feet away. To have it engage the public so readily is fantastic. I do love Instagram. I think it’s the perfect tool for a visual artist.

Does what you see when you browse Instagram inspire you, or is it simply a place to proliferate and publicize your art?

I’ve started to make a lot of sunset paintings, and I was really just working from other people’s sunset images on their Instagram feeds, then writing text on that. I found that to be funny because there was a while, a few years ago, where everybody was posting their lunch on Facebook, and I didn’t find that very inspiring, but I did find it inspiring to see these gorgeous sunsets as a background for things that I write. I don’t look at Instagram so much for inspiration from other people’s art as much as I look at people’s casual photographs as inspiration.

What comes first for you, the image or the language?

My process is that I see an image that is interesting to me, and I’ll draw it. I’ll have a pencil or ink drawing, and the text comes to me in the process of making it. Usually it’s a reference to what I’m going through or seeing while I’m trying to make this drawing. Then the words begin to take over, and by the time I get to canvas or to the larger paper pieces that I do, I know what the text is going to be. It’s interplay on both ends, but in the earlier stages, the images are the things that make me come to the text.

How do politics and current events influence your work, if at all?

They definitely influence me. I have found it political to criticize the American dream for a long time, because it seems like something that we were all served up as a possibility, and I recognized a very long time ago that the American dream is not possible for everyone. It’s just a carrot stick they dangle in front of us. I find that to be political, in a way, because I think we’re being sold things all the time by politics. Right now, we’re living in an incredibly strange moment in politics where what we are told through the media and through politicians’ mouths is often untrue, or we know it’s not true, or it doesn’t make any sense, and yet it keeps on happening. That’s been true since we went to war in Iraq. Politics are very much part of my work because I’ve dealt in trying to make sentences and words that somehow sit on the razor blade of being true and fake at the same time, or being positive and negative at the same time. I’m always trying to speak in double entendres, and that has a lot to do with politics and political-speak.

You Might Also Like