David Toole, dancer and actor who thrilled the crowd at the 2012 Paralympics opening ceremony – obituary

David Toole, the dancer and disability rights advocate, who has died aged 56, was a disconcerting but undoubtedly brilliant performer who made a sensational appearance flying over the Olympic arena in the 2012 London Paralympics opening ceremony.

Born in Leeds with embryonic legs which were amputated when he was an infant, he could skip, scuttle, jump and turn on his hands and huge arms with a stage command and grace beyond most of the best of his able-bodied colleagues.

“People say it’s like I’m weightless and I can fly,” he once said. “But it’s just there in the way I move. That’s the way I’m built with my centre of gravity.”

Toole was the central focus of some of the most memorable British dance theatre of the past 25 years, portraying misfits in unforgettable imagery. The Daily Telegraph critic commented: “He has hands that can powerlift one moment or beckon in 17 subtly different ways. His pugnaciously featured face can freeze an audience with a look, crack into a grin, or display profoundest grief. When he dances, you see a man and a stage made for each other.”

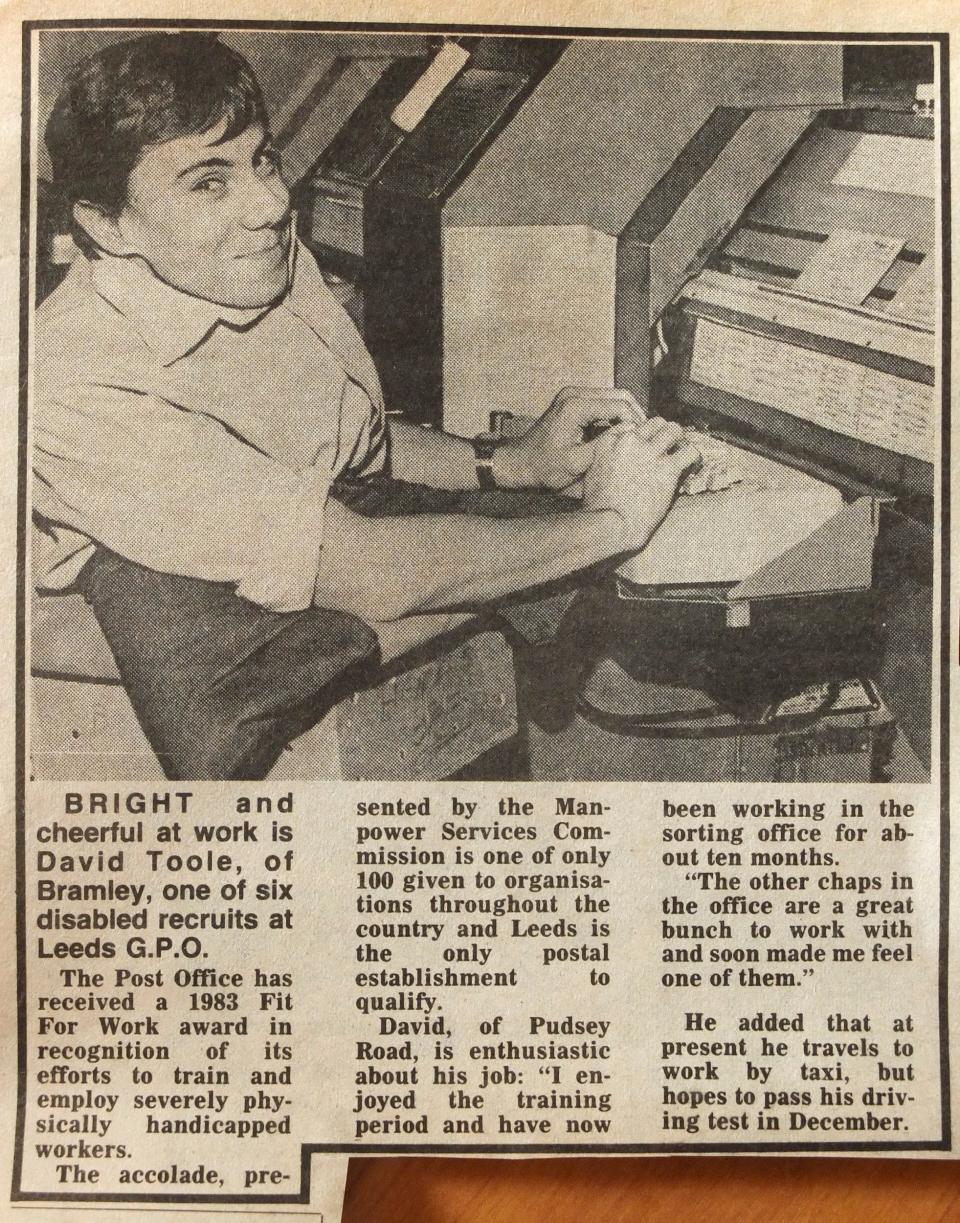

Having worked as a postman for nine years, Toole turned to dance in his late 20s and immediately emerged as the focal point of the Candoco dance company, a pioneering ensemble of disabled and able-bodied performers launched in 1993.

But it was when he joined Lloyd Newson’s controversialist troupe, DV8 Physical Theatre, that Toole found a choreographer of the stature and ingenuity to exploit his unique capacity for making politically powerful and emotive images, challenging ideas about human society.

In a striking 2007 film of DV8’s production The Cost of Living, Toole played a double-amputee performer determined to make an independent living on the Norfolk seafront, along with his aggressively supportive mate Eddie and a community of misfits.

Perched on the back of an able-bodied dancer who was prowling on all fours, Toole’s half-body appeared to fuse with the other, creating a surreal effect of two men sharing a single pair of legs. He would skip on and off his wheelchair as if to claim his right to two separate living environments.

Dance, for Toole, was a release, giving permission for people to look at him and see him as he was. “It’s weird to think that if I’d been born with useful legs, I might never have become a dancer. My so-called disability has enabled me to achieve so much.”

David Vincent Toole was born in Leeds on July 31 1964, the younger child of Jean (née Dawson) and Terrence Toole. His mother was a nurse, his father a Newcastle shipyard worker who moved to Leeds as a joiner, and in the evenings performed a song and comedy double act with his brother around northern clubs and pubs.

Their son was born with sacral agenesis, a rare congenital defect, which is often treated with early amputation of unformed legs. The boy attended John Jamieson School, a special school in Leeds, and did a computing course as Leeds University before joining the Post Office.

Bored, he joined a dance workshop in Leeds for a group planning a disability dance troupe. When he told his mother he intended to become a professional dancer she reminded him that he had no legs. Once Candoco launched, Toole gave up the Post Office and combined part-time performing with a BA course at the Laban dance school in London.

Candoco was welcomed worldwide for its statement about disability, and Toole was the undoubted star of the productions, bringing a bold physical attack denied to most of the other performers. Touring for most of the 1990s was “like being in a rock group”, he said. His versatility was quickly noticed and in 1995 he played Puck in a production of Britten’s opera A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

A year later Toole showed wider acting potential in a role in Sally Potter’s feature film The Tango Lesson. With Graeae disabled theatre, he would star as the disfigured De Flores in Middleton and Rowley’s Jacobean tragedy The Changeling, as well as in Sarah Kane’s Blasted.

Toole’s extraordinary impact in DV8’s Cost of Living in Sydney should have been developed in a world tour, but his kidneys failed, and in 2002 he had a transplant. Newson restaged the production without him at the Tate Gallery in 2003, but it was after Toole’s recovery that Newson was able to make his now classic film.

The Cost of Living won awards worldwide, including a Prix Italia and a Rose d’Or. “Nearly every scene strikes the heart,” wrote the New York Times.

Toole then had cameos in Michael Apted’s 2006 film about William Wilberforce, Amazing Grace, and a 2007 episode of the television drama series Rome. Meanwhile he was active in disability theatre and dance in London, working with Frontline, Swung Low and Stopgap.

When Graeae’s director Jenny Sealey coordinated the 2012 London Paralympics opening ceremony, Toole was given the climactic coup de théâtre, flying high over the stadium while Birdy sang Anthony and the Johnsons’ Bird Gerhl.

Toole was frank about his compromises in Kim Farrant’s award-winning 2007 documentary, Naked on the Inside. “I like my eyes, I like my hands, my arms are OK – after that I start running out of options. But you look at your good points, and use them to your advantage,” he said.

In 2013, for the West Yorkshire Playhouse, he devised a show twinning his own story with that of the “Amazing Half-Boy”, Johnny Eck, a 1930s performer who also lost his legs through sacral agenesis, and became a US freak show sensation, starring in Tod Browning’s 1932 film Freaks and Tarzan movies.

Toole’s final performances were with Stopgap. He was acclaimed in the surreal 2015 Edinburgh Fringe Festival show, Artificial Things, where he was locked inside a glass box, and Sophie Fiennes made an award-winning 2018 film. In spring 2019 he played a father grieving for his wife’s loss in The Enormous Room.

Soon afterwards he was struck down by a recurrence of kidney disease. Increasingly restricted by dialysis treatment, he tweeted wryly in the summer that it was the first time that he had ever felt disabled.

David Toole was appointed OBE in 2019 for his services to dance and to disability advocacy, but was unable to attend Buckingham Palace for his investiture last May.

He is survived by his sister.

David Toole, born July 31 1964, died October 16 2020