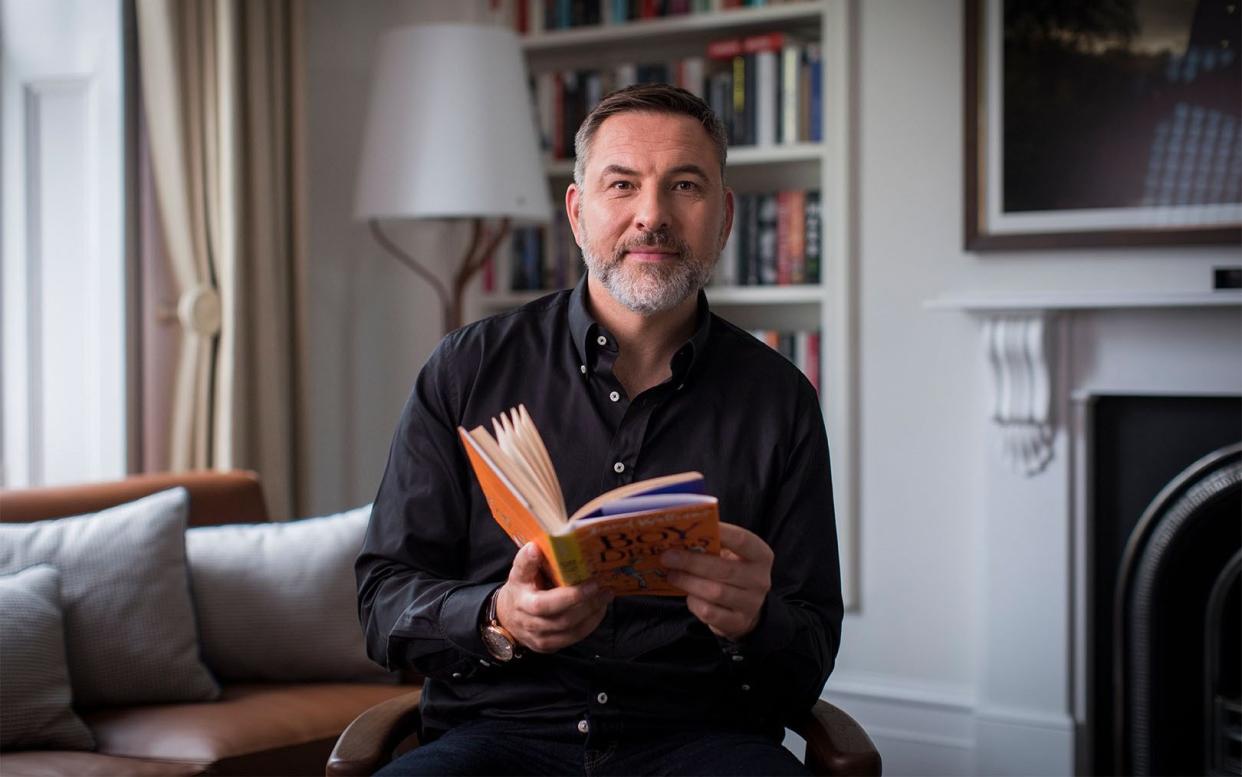

David Walliams: ‘Storytelling is within us all – it’s just about unlocking it’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I understand completely why “author” recently came top in a survey of the most desirable professions. Take it from me – it is the best job in the world. Now is a great time to get your children into the storytelling habit. Writing is an amazing escape, enabling children to take themselves off into an imaginative world, and apart from walking around the park, there is nothing else to do at the moment.

As part of a new BBC online service called Maestro, I am presenting a course of 25 lessons on how to write children’s stories.

For me, storytelling all started with toys. Children are constantly creating narratives, even if they don’t realise it. Steven Spielberg has said that every kid is like a movie director, moving their toys around, making the characters fight each other and going on adventures.

I was exactly like that as a child. I remember loving being in my bedroom, playing with my Star Wars toys and creating stories with them. That storytelling urge is within us all. It’s just about unlocking it.

I soon became as fascinated by books as I was previously by toys. I have a lovely memory of my Dad reading Dr Seuss’s Green Eggs and Ham to me at bedtime. I remember it so clearly because the images from the book are so bizarre. If you read Dr Seuss before bedtime, it’s very trippy. It conjures up this weird world, which is quite disturbing and nightmarish. It’s like “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” from Fantasia – things keep building and building and becoming more and more extreme and strange.

I remember finding it a bit upsetting, but also really intriguing. I loved it. From that moment, books had me hooked. Nothing beats reading for pleasure. There is nothing better than kids reading a story just because they really want to. I was soon devouring books. I loved Stig of the Dump. I was immediately intrigued by the story of a boy who makes friends with a caveman. There is a great mystery to it. Stig lives in a dump, but is he a real caveman? How did he get there? It grips you from the start.

I also adored Charlie and the Chocolate Factory – it instantly captivated me. I often read it again now. I’m reading a lot of Roald Dahl with my son at the moment. You can read his stories any number of times and still really enjoy them. They are so imaginative. Willy Wonka’s inventions are just incredible, and something extraordinary happens in every chapter.

To me, it’s like Star Wars. It’s got a hundred great ideas in it. You could write a good book with just two great ideas, but this has a hundred. Everywhere you look, something magical is happening. You’re properly transported to another world. That book never dates. It’s a classic that will go on forever. Years later, I was inspired to start writing my own children’s books. When Matt [Lucas] and I were doing Little Britain in the early Noughties, a young boy wrote me a letter. He explained that his school had a fancy-dress day where they were allowed to go in wearing whatever they liked and that he had gone dressed as Emily Howard, a character I played in that series. That started me thinking: “What if a boy wanted to wear a dress to school every day, and not just for fancy-dress day? Why would he do it? How would his family react? Would anything happen because of it?” That fired me up to begin writing The Boy in the Dress.

Imagination is so important. Which is why I am so keen to encourage children to try their hand at writing stories themselves. But what help can you give your children to get started? The main piece of advice I give to aspiring young writers is to remember that it should be fun. Some kids find writing tough because it can feel like work, but it shouldn’t, because you’re going to go on a magic journey using your imagination: you are going to fill a blank piece of paper with an amazing story and characters, jokes, dramatic situations and scary monsters, all things that didn’t exist before.

Children should also write the sort of stories they would like to read themselves. If your thing is monsters or space or football or undersea adventures, write about that. You can really go for it and explore things you genuinely care about. You can never really guess what people will want to read, so just aim to please yourself. The chances are that if you are entertaining yourself, then you will entertain other people, too.

Starting a book is, of course, the hardest part. When you don’t know what you’re going to write, that can be very daunting. But everyone can picture events that would never happen. It is easier to start by talking about ideas rather than sitting down in front of a blank sheet of paper straightaway. It often works to ask children lots of questions: What do you think would be the scariest monster? Where does he live? What does he say? Does he eat children? That often gets their minds whirring, and all of a sudden they have got the beginning of a story.

Also, try to make sure you have a first sentence that’s really intriguing. So if you open with, “It was another boring day in the boring town,” that’s not going to interest the reader. But if you start with, “Something very strange was happening in the town that day…”, the reader thinks, “Oh, what is it?” We are humans and we are naturally intrigued by stories. Every chapter should end with a cliffhanger, so the reader is constantly saying, “What’s next? What’s next?”

The other thing to remember about writing is that practice makes perfect. Like anything in life, you only learn about something by doing it. I remember Dec Donnelly talking to me about Malcolm Gladwell’s famous theory about expertise and saying: “Ant and I have had 10,000 hours of practice presenting live TV.” The more you do something, the better you get at it.

Don’t expect instant perfection. Before I wrote The Boy in the Dress, in my head it was perfect. Then of course I started to write it, and I saw it was much harder than I’d imagined. I realised I should lower my ambitions a bit. It worked for me – and can for budding novelists of the future, too.

As told to James Rampton

To watch David’s lesson series on how to get into writing, go to BBC Maestro