The Davis-Douglas Farm in Plymouth preserves both land and notable family histories

PLYMOUTH − The stories he heard as a curious child playing at his grandmother's knee in South Plymouth were quite grand, Sam Chapin recalls.

"Some people I've talked to would recall my grandmother's family arriving from New York for the summer," Chapin said. "It was a bit of a spectacle, an entourage of servants and maids, steamer trunks, arriving in Plymouth by train in early June, staying until late September."

The dirt road that his grandmother lived on was off Long Pond Road, 7 miles from the Cape Cod Canal. Ruth Davis had married Theodore Steinway, of the piano manufacturing family. Next to her house, which Sam visited, was the summer home of her late father, Howland Davis, Sam's great-grandfather.

Howland Davis was a Plymouth boy who had gone to Harvard and became a successful New York investment banker. His house had a large Italianate garden created by Joseph Everett Chandler, a noted architect and landscape designer of many Boston landmarks, including the restoration of the Paul Revere House.

He died in 1930; his wife, Anna Shippen Davis, lived until 1945. The couple resided in New York but also left 25 acres in Plymouth with four houses, a large barn, a rolling meadow, woodlands and a water tower with views of the Sagamore Bridge.

Almost a century later, the two homes are separate from the rest of the family property, which in 2012 was donated to the Wildlands Trust, just across Morgan Road.

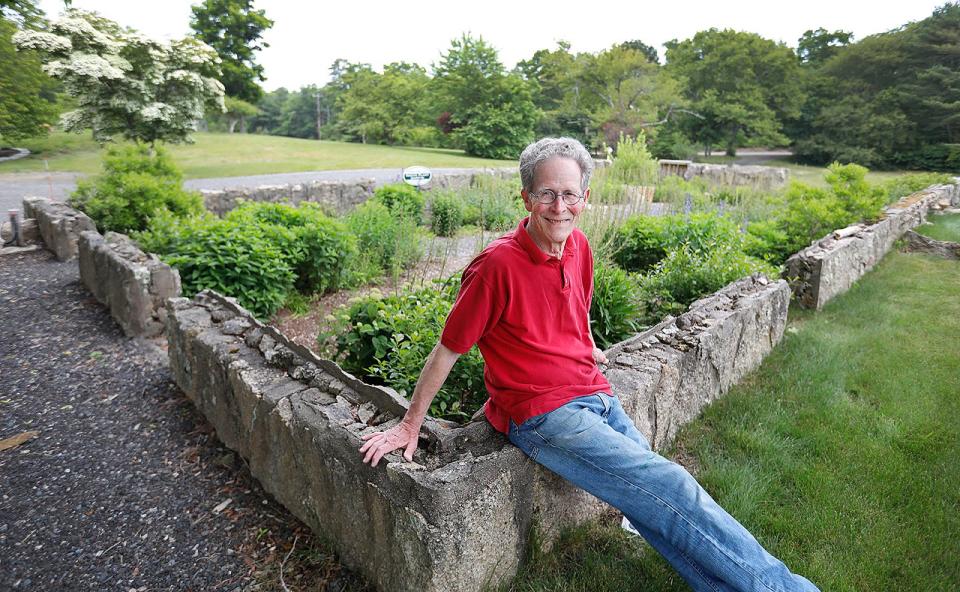

The Davis-Douglas Farm is now the trust headquarters; Sam Chapin is chairman of the board.

Chapin, 72, lives in his grandmother's former house with his wife, Caroline, past director of The James Library and Center for the Arts in Norwell.

Next door, a descendant of Hester Howe, Howland Davis' eldest daughter, lives in Sam Chapin's great-grandfather's house.

"This is a story of two families (the Davises and the Douglases), but it is mainly a story of historic preservation and land restoration," Chapin said.

Howland Davis was the son of William T. Davis, a prominent 19th-century Plymouth historian. The local history room at The Plymouth Public Library has a file devoted to William T. Davis; his book "Ancient Landmarks’’ forms the basis of knowledge about Plymouth’s 19th-century landscape and residents.

The Long Pond property's transformation − from a local family's homestead, to a summer getaway for a wealthy New York clan, to a working farm for both, to today's conservation refuge − is a story of hard work, social status, business connections, friendships and generosity.

"My great-grandfather started it all − this story of both families who were interested in preserving what they had rather than selling it off to developers," Chapin said.

In the 1880s, Howland Davis was sent from Plymouth to New York to open a new bank branch. He and his wife, Anna, began assembling what would become 25 acres of meadows and tree lands on the eastern shore of Long Pond.

By 1890, they had built a summer home there. Then the Great Fire of 1900 roared through, burning woodlands from Carver to Cape Cod Bay, including the Davis property but not the house. A local newspaper of the day reported that the fire left nearly half of the town a barren waste.

Howland and Anna Davis cleared the charred stumps and decided to start a farm to support their growing family of eight children. It was the age before the automobile; the nearest stores were far away. The gentleman's farm would be used to grow vegetables, raise chickens and have a milk cow or two. A farmhouse and a barn were built.

Howland Davis commuted to and from New York City, taking the steamboat to Fall River and then traveling by train to Middleboro and Plymouth.

By 1922, a local couple, Percy and Agnes Douglas, had been hired to run the farm. They moved into the farmhouse and tended to vegetable gardens, fruit trees, berry patches, chickens, dairy cows, pigs and horses. There was also a chicken house and a native-stone water tower with water pumped from Long Pond.

The children of the prominent Davis and working-class Douglas families worked alongside one another and played baseball in the fields. During both the Depression and World War II, the farm became an important source of food.

In her 1943 diary, Sam's grandmother wrote: "Working from 8 to noon, 5 days a week. 35 quarts of strawberries brought in. ... The farm garden is remarkable. So many cucumbers we couldn't use them all."

By the 1950s, the postwar period was a new era and the farm was no longer needed. The lives of the Davis family revolved around social circles and New York City cultural institutions, including the Metropolitan Opera and other locations.

The eight children of Howland and Anna Davis agreed to give the 7-acre farm to Percy and Agnes Douglas, who had raised their eight children there.

One of the children, Barbara Douglas, had married Enzo Bongiovanni, of Plymouth, who renovated the chicken house into a small home, and they moved in, raising three sons.

From the 1970s into the 1990s, Plymouth experienced a 145% growth spurt, and by the early 2000s, the land was considered well-suited for development.

Both Percy and Agnes Douglas died in 2008. In 2012, the Bongiovanni sons sold the property to the Wildlands Trust for $450,000, which was considered a bargain. They hoped to preserve it.

Sam Chapin credits Karen Grey, the Wildland Trust's former director, with the vision and drive to turn the farm into the trust headquarters once the land became available.

In a 2011 letter, David Bongiovanni, Percy and Agnes' Douglas' grandson, wrote from New Hampshire of his family's desire to preserve both the Davis and Douglas heritage at the farm as well as "the privacy and integrity of the neighborhood we have all cherished for decades." He supported the trust's planned restoration.

The Wildlands Trust made a series of significant changes. Opting to use the former farmhouse as its headquarters, the Trust renovated the structure, adding a new foundation and a 1,000-square-foot addition, mostly below grade, which is climate controlled, ideal for storing archives and providing workspace for the stewardship crew.

The open grassy meadow now has a community garden: 17 raised beds and three standing beds are loaned out to residents needing a space to grow vegetables and flowers.

The former barn, demolished in the 1990s, is where a native plant garden now sits, with the barn foundation visible around the border. The new community education center, built near the old barn, hosts scientific and public land-preservation programs and has a meeting room of 100 seats.

There are walking trails in the woodlands off Long Pond Road and there is a new trailhead behind the restored farmhouse/office. A kiosk has maps, historical photos and pamphlets with a brief history.

You find the Davis-Douglas Farm by taking the Clark Road exit from Route, 3, heading south for about a mile on Long Pond Road. You see the Wildlands Trust sign on the right at 675 Long Pond Road, pull in and on the right near the road stands the water tower. It is still the highest point on the property.

Near the restored farmhouse you will find a large oak tree, believed to have been planted in 1850.

Some regard it as the farm's spiritual center.

For more information, call 774-343-5121, email info@wildlandstrust.org or visit wildlandstrust.org.

This article originally appeared on The Patriot Ledger: The Davis-Douglas Farm in Plymouth is home to the Wildlands Trust