The day an airliner took off, dived down — and vanished into the Florida swamp

It vanished with barely a trace.

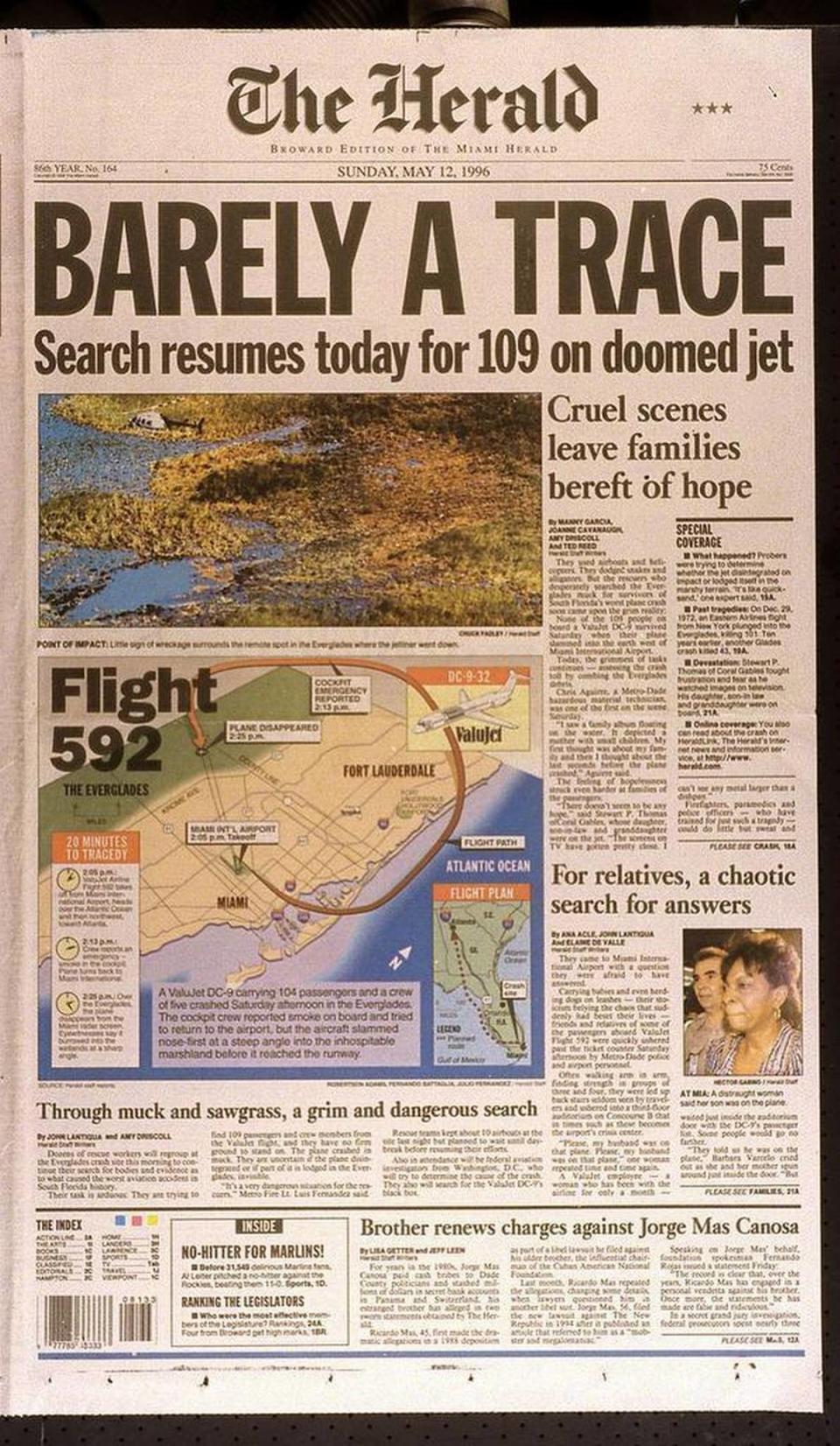

ValuJet Flight 592, with 110 people on board, plunged into the Everglades after taking off from Miami International Airport on May 11, 1996.

The DC-9 had traveled less than 100 miles west of the airport when the crew reported smoke in the cockpit. The pilot turned around and tried to make it back.

Atlanta-bound Flight 592 slammed nose-first into the muck and disappeared.

Investigators later determined that 144 oxygen-generating canisters were improperly secured, labeled and packaged in the cargo hold of the plane.

Here is a look at the tragedy through the Miami Herald archives:

READ MORE: See the original Miami Herald website coverage from 1996

THE CRASH

Published May 12, 1996

By airboat and helicopter, rescuers searched the muck and shallow water of the Everglades, but they quickly stared at the grim reality: None of the 109 people on board a ValuJet DC-9 survived when their plane slammed into the earth west of Miami International Airport on Saturday.

“Oh, no. Not the day before Mother’s Day, “ said one frustrated Metro firefighter, pulling off his sweaty flame retardant gear.

The feeling of hopelessness struck even harder at families of the passengers:

“There doesn’t seem to be any hope, “ said Stewart P. Thomas of Coral Gables, whose daughter, son-in-law and granddaughter were on the plane. “The screens on TV have gotten pretty close. I can’t see any metal larger than a dishpan.”

Firefighters, paramedics and police officers — who have trained for just such a tragedy — could do little Saturday afternoon but slosh through the mud. At times, it seemed only the dragon flies and mosquitoes easily visited the wreckage.

Bodies were sighted, but fuel that could have been easily ignited and the natural terrain hampered rescue efforts to the point where even airboats were eventually prohibited from skimming the river of grass to help.

“It is just all swamp and sawgrass. It will probably take three or four days to clean up. It will all have to be all done by airboat, “ said J.C. Esslinger, a state wildlife officer. “It is going to be ugly out there. It’s not going to be pleasant, that is for sure.”

ValuJet Flight 592 took off from Miami International at 2:05 p.m. — one hour late — with 104 passengers and a crew of five, said Federal Aviation Administration spokeswoman Christy Williams.

It was scheduled to land one hour and 55 minutes later in Atlanta. Instead, after about 20 minutes, it bored into the ground like a power drill.

“What we have is a high-impact crash, “ said a somber Luis Fernandez, spokesman for the Metro-Dade Fire Department.

The FAA’s Williams gave this account of Flight 592’s last minutes:

The DC-9 took off and had traveled less than 100 miles west of Miami, when the crew radioed Miami traffic controllers to report smoke billowing into the cockpit. The plane had been airborne eight minutes.

Headed back to airport

The jet, then at an altitude of 10,500 feet, turned around and tried to make it back to Miami International.

At about 2:25 p.m., Miami air traffic control lost Flight 592 from its radar screens. The jet went down, apparently nose first, about 14 miles northwest of Miami International.

It disintegrated on impact in a desolate area of wet earth, grass patches and trees.

A private pilot from Miami Beach who was flying west at the time told Cable News Network he saw the plane go down. Daniel Muelhaupt said he was about two miles from the plane, flying toward Naples, when he saw what he at first thought was a small plane doing maneuvers. The craft was pointing down at an angle of about 75 degrees.

“When it hit the ground, the water and dirt flew up, “ Muelhaupt said. “The wreckage was like if you take your garbage and just throw it on the ground, it looked like that.”

Muelhaupt said he radioed authorities and circled until they reached the scene, which took a long time because there were no visible flames or large chunks of aircraft to focus on.

“Access was a major, major problem. The plane was broken up into many pieces and submerged in 4 to 5 feet of water.” said Metro-Dade’s Fernandez.

Helicopters from the U.S. Coast Guard, Metro Police and the Dade fire department finally located the crash site and reported no signs of survivors, just minuscule pieces of shredded metal, baggage, bodies and a taut crater shaped like a candle flame. The crash sight is very close to where an Eastern Airlines L1011 crashed in 1972, the worst local air disaster before Saturday.

While rescuers searched in vain, distraught relatives of passengers rushed to the ValuJet counter at Miami International. Company officials quickly moved them to an auditorium, where counselors were available to help them deal with their loss.

Saturday afternoon, ValuJet’s president spoke from Atlanta.

“It’s impossible to put into words how devastating something like this is, “ said Lewis Jordan, president and chief operating officer.

Atlanta-based ValuJet, which began operations in October 1993 and serves 26 cities in 17 states, has had a checkered past.

The airline has been one of the most successful startups in aviation history, but its rapid growth has been tainted by several accidents and questions about the reliability of its aged fleet.

The FAA has ValuJet under a special emphasis inspection because of repeated safety problems.

Last summer, the FAA issued a special inspection notice for aircraft engines that ValuJet purchased from a Turkish airline.

That investigation stemmed from a June 8, 1995, fire that destroyed a ValuJet DC-9 on a runway at Atlanta. One flight attendant was burned and minor injuries were reported as the 57 passengers and five crew were evacuated.

In January, a ValuJet DC-9 got stuck in the mud at Hartsfield Atlanta International Airport. The 101 passengers were bused to a terminal.

Also in January, another ValuJet DC-9 with 30 people aboard slid into a snowbank after landing at Dulles International Airport outside Washington, closing the airport for nearly three hours. No one was hurt.

A ValuJet DC-9 also skidded off an icy runway at Dulles in January 1994, closing the airport for almost two hours.

Flight 592 was a McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 configured with 113 passenger seats. It is powered by Pratt & Whitney JT8D-9A engines.

At the crash site, Metro fire and the Florida Game and Freshwater Fish Commision officers gathered about a half mile from the crash on the levy of the L-67 Canal. Helicopters landed on the ridge dropping off firefighters.

About 5:30 p.m., police and rescue were waiting for hazardous material specialists to check out the area before going in. There was concern about possible fuel leakage and explosion.

“We have to wait until Haz Mat cleans it up, “ said E.M. Davis, a fresh water and game commission officer.

But as night came on, the search was called off. Rescue officials said the fuel atop the water posed too much of a risk for the airboats.

“Night is falling, we’re going to secure things here and make sure no one molests the area. We won’t be going out there tonight, “ said Metro-Dade Police Capt. Rita Oramas.

THE SEARCH

Published May 12, 1996

They used airboats and helicopters. They dodged snakes and alligators. But the rescuers who desperately searched the Everglades muck for survivors of South Florida’s worst plane crash soon came upon the grim reality:

None of the 109 people on board a ValuJet DC-9 survived Saturday when their plane slammed into the earth west of Miami International Airport.

Today, the grimmest of tasks continues — confirming the crash toll by combing the Everglades debris. Chris Aguirre, a Metro-Dade hazardous material technician, was one of the first on the scene Saturday.

“I saw a family album floating on the water. It depicted a mother with small children. My first thought was about my family and then I thought about the last seconds before the plane crashed,” Aguirre said.

The feeling of hopelessness struck even harder at families of the passengers: “There doesn’t seem to be any hope,” said Stewart P. Thomas of Coral Gables, whose daughter, son-in-law and granddaughter were on the jet. “The screens on TV have gotten pretty close. I can’t see any metal larger than a dishpan.”

Firefighters, paramedics and police officers — who have trained for just such a tragedy — could do little but sweat and slosh through mud. At times, it seemed only the dragonflies and mosquitoes easily visited the wreckage. Bodies were sighted, but fuel that could have been easily ignited and the natural terrain hampered rescue efforts to the point where even airboats were eventually prohibited from skimming the river of grass to help.

“It is just all swamp and sawgrass. It will probably take three or four days to clean up. It will all have to be all done by airboat,” said John Esslinger, a state wildlife officer. “It is going to be ugly out there. It’s not going to be pleasant, that is for sure.”

Television news helicopters circled the site all afternoon, showing South Florida and the world the same bleak view: bits of debris dotting the shallow water and hammocks.

ValuJet Flight 592 took off from Miami International at 2:05 p.m. — one hour late — with 104 passengers and a crew of five, said Federal Aviation Administration spokeswoman Christy Williams. The DC-9, one of aviation’s great workhorses, was scheduled to land one hour and 55 minutes later in Atlanta.

Instead, after about 20 minutes, the white blue and yellow aircraft bored into the ground like a power drill.

“What we have is a high-impact crash,” said a somber Luis Fernandez, spokesman for the Metro-Dade Fire Department.

The FAA’s Williams gave this account of Flight 592’s last minutes: The DC-9 took off to the east and then turned northwest. It had traveled less than 100 miles from Miami when the crew radioed Miami traffic controllers to report smoke billowing into the cockpit. The plane had been airborne eight minutes.

The jet, then at an altitude of 10,500 feet, turned around and tried to make it back to Miami International. At about 2:25 p.m., Miami air traffic control lost Flight 592 from its radar screens.

The plane went down, apparently nose first, about 14 miles northwest of Miami International. It crashed in a desolate area of wet earth, grass patches and trees.

A private pilot from Miami Beach who was flying west at the time said he saw the plane go down.

Daniel Muelhaupt said he was about two miles from the jetliner, flying toward Naples, when he saw what he at first thought was a small plane doing maneuvers. The plane was pointing down at an angle of about 75 degrees.

“When it hit the ground, the water and dirt flew up,” Muelhaupt said. “The wreckage was like if you take your garbage and just throw it on the ground, it looked like that.”

On the ground, Sam Nelson and Chris Osceola said they were on a bass boat fishing on the L-67 Canal about a half-mile from the crash when they saw the plane begin to falter.

“The plane was going when all of a sudden it just made a right turn. I don’t know what it was doing. It looked like it was trying to go back up. It was pretty low,” said Nelson, 52, of Hollywood. “It kinda turned sideways, then it just nose dived, right down straight into the swamp.”

The two men brought the boat to land and ran up on the levee to look, thinking they could help.

“The last thing we saw was the tail end going down,” Nelson said. “Then it hit and there was a big, big explosion. You could hear the motor, like it was under full power. That thing hit so hard you couldn’t even see it. After the explosion went away, there was no smoke. It was like nothing ever happened.”

Muelhaupt, the small-plane pilot, said he radioed authorities and circled the crash site until rescuers reached the scene, which took about a half hour because there were no visible flames or large chunks of aircraft to focus on.

Helicopters from the U.S. Coast Guard, Metro Police and the Dade fire department circled the crash site and reported no signs of survivors, just minuscule pieces of shredded metal, baggage, bodies and a taut crater shaped like a jagged candle flame.

“Access was a major, major problem. The plane was broken up into many pieces and submerged in 4 to 5 feet of water.” said Metro-Dade’s Fernandez.

The site is very close to where an Eastern Airlines L1011 crashed in 1972, the worst local air disaster before Saturday.

While rescuers searched in vain, distraught relatives of passengers rushed to the ValuJet counter at Miami International. Company officials quickly moved them to an auditorium, where counselors were available to help them deal with their loss.

At Gate G-2, a sign announcing the departure of Flight 592 still was listing it as “On Time.”

Saturday afternoon, ValuJet’s president spoke from Atlanta. “It’s impossible to put into words how devastating something like this is,” said Lewis Jordan, president and chief operating officer.

Atlanta-based ValuJet, which began operations in October 1993 and serves 31 cities in 19 states, has had a checkered past. The airline has been one of the most successful startups in aviation history, but its rapid growth has been tainted by several accidents and questions about the reliability of its aged fleet.

The FAA has ValuJet under a special emphasis inspection because of repeated safety problems. Last summer, the FAA issued a special inspection notice for aircraft engines that ValuJet purchased from a Turkish airline. That investigation stemmed from a June 8, 1995, fire that destroyed a ValuJet DC-9 on a runway at Atlanta. One flight attendant was burned and minor injuries were reported as the 57 passengers and five crew members were evacuated.

Flight 592 was a McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 configured with 113 passenger seats. It was powered by Pratt & Whitney JT8D-9A engines.

At the crash site, Metro fire and the Florida Game and Freshwater Fish Commission officers gathered about a half mile from the wreckage on the levee of the L-67 Canal. Helicopters landed on the ridge dropping off firefighters.

About 5:30 p.m., police and rescue workers were waiting for hazardous material specialists to check out the area before going in. There was concern about possible fuel leakage and fire.

“We have to wait until Haz Mat cleans it up,” said Ernest Davis, a wildlife officer.

But as night came on, the search continued with a handful of airboats equipped with floodlights and generators. More workers were expected to join the effort at daybreak today.

Nelson, the bass fisherman who saw the plane go down, said that hours later his heart was still racing.

“It was something I will never ever forget,” he said.

THE SCENE

Published May 12, 1996

Late Saturday, rescue crews were trying to determine whether the ValuJet aircraft disintegrated on impact or partially lodged itself in the soft, marshy terrain of the Everglades.

The area where Flight 592 crashed Saturday is thick with razor-tooth sawgrass and a variety of wildlife, including alligators. Popular with airboaters, froggers and fishermen, the swampy muck beneath the water may have acted as a pincushion, essentially swallowing the disabled DC-9 aircraft.

“That’s why you don’t see big parts of it,” theorized Harold Johnson, vice president of the Everglades Coordinating Council and an airboater familiar with the area. “It may have just swallowed it up. It’s like quicksand. It doesn’t have a bottom.” Maj. Jim Ries of the Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission said that’s a likely scenario, depending on the trajectory of the aircraft on impact.

“It looks like a large part of the airplane must be below the muck and mud. That stuff can be very deep before you hit shell rock,” or limestone, Ries said.

May is generally the dry season in the Everglades, with water only one to three feet deep. During the rainy season, it can reach five feet in places. Alligators in the area can grow to 12 feet or more in length.

But Steve Coughlin, a biologist with the game and fish commission, said they probably pose no threat to searchers.

“Usually something like that scares wildlife away,” he said. “And if there’s fuel or oil or anything like that in the water, alligators won’t get anywhere near there.”

Coughlin said the crash isn’t likely to pose a hazard to wildlife or water quality in the area. But salvaging what’s left of the aircraft may be difficult since it’s nearly impossible to get heavy equipment into the area.