The Day Big-Time College Football Came to the South

The galloping popularity of radio in the 1920s was an unexpected but welcome boon to the already popular University of Georgia football team. Now it was possible for fans from the Appalachian foothills to Atlanta to the Atlantic coast to hear live broadcasts of the games without leaving their homes. This naturally fed a hunger to witness the contests in person, and soon Athens was clogged on Saturday afternoons with the cars of fans pouring in from all corners of the state. The town fathers began debating the need for additional parking and wider streets to handle the influx. The weekend of the annual Georgia-Auburn game devolved into a spectacular bacchanal marked by the pursuit of such popular pastimes as “dissipation, licentiousness, even lawlessness,” in the words of one alarmed critic.

Then there was the violence—and the growing professionalism—of the game itself. Way back in 1897, when gang tackling, flying wedges and other vicious tactics began to dominate play, a Georgia player had died from injuries sustained during a game against Virginia. In addition to the violence there was the ugly little secret that some of the Georgia football players were not even registered as students while others were so academically deficient that they gained admission by enrolling in the law school, where admission requirements were minimal. “Effectively,” the historian Thomas G. Dyer wrote, “a double standard operated well before the turn of the century.” And it was destined to enjoy a long life.

During the 1905 season, 18 college football players died from injuries incurred on the field. The following year, President Roosevelt convened college administrators to discuss ways to limit injuries, which led to the formation of the Intercollegiate Athletic Association, soon renamed the National Collegiate Athletic Association. It standardized rules with an eye to reducing violence and injuries but showed little interest in stemming the flow of money into intercollegiate sports, a flow that was lubricated by the advent of radio. By the Twenties, players had become paid mercenaries, accepting cash under numerous tables and repeatedly switching schools, sometimes in mid-season. At Georgia, the answer was not to clean up this “amateur” sport and purge it of money; the answer was to build a bigger football stadium that would bring in even more money.

Excerpted from The Age of Astonishment: John Morris in the Miracle Century—From the Civil War to the Cold War by Bill Morris.

In the 1890s [my grandfather] John Morris had played on the university’s very first sports team, its baseball team, which was little more than an informal club. It surely galled him that now, after 30 years on the faculty, he was earning less than the school’s football coaches, and it just as surely delighted him that there were voices, including a student publication called The Iconoclast, that spoke out strongly against the lopsided and growing emphasis on athletics, the existence of separate academic standards for athletes, and the campaign to build a massive, and expensive, new football stadium. The student editors pointed out that no athlete ever flunked out of the University of Georgia. For this heresy they were expelled from the University of Georgia.

Such iconoclasts were no match for the exposure, rabid fan loyalty—and revenue—the Bulldog football team was generating. And so plans were unveiled for a $360,000 stadium to be built in the ravine carved by Tanyard Creek, where as boys John and his brothers had given wide berth to the vicious dogs guarding the Irishmen’s tanneries. Part of the money came from a loan from the Trust Company of Georgia backed by the newly formed Georgia Athletic Association, made up of fans and alumni. This independent fiefdom would become, to the chagrin of generations of chancellors, a magnet for money and the power that comes with it—and, eventually, for the abuse that always comes with unbridled power.

A local celebrity had moved in next door to the Morris family. His name was Vernon Smith but everyone called him Catfish because, according to legend, at his high school graduation in Macon he had won a 25-cent bet by biting the head off a live catfish. His celebrity came from his stellar play on the Georgia football team as both an offensive end and a defensive mayhem artist. At 6’2” and 190 pounds he was a giant to my seven-year-old father, who trailed after him like a lost puppy. “He would take me around the neighborhood for walks,” my father recalled, “and he sort of befriended me. He said to me once, ‘Richard, you can call me Vernon.’ I was the only one in town who got to call him Vernon.” With a laugh, my father added, “What a role model!”

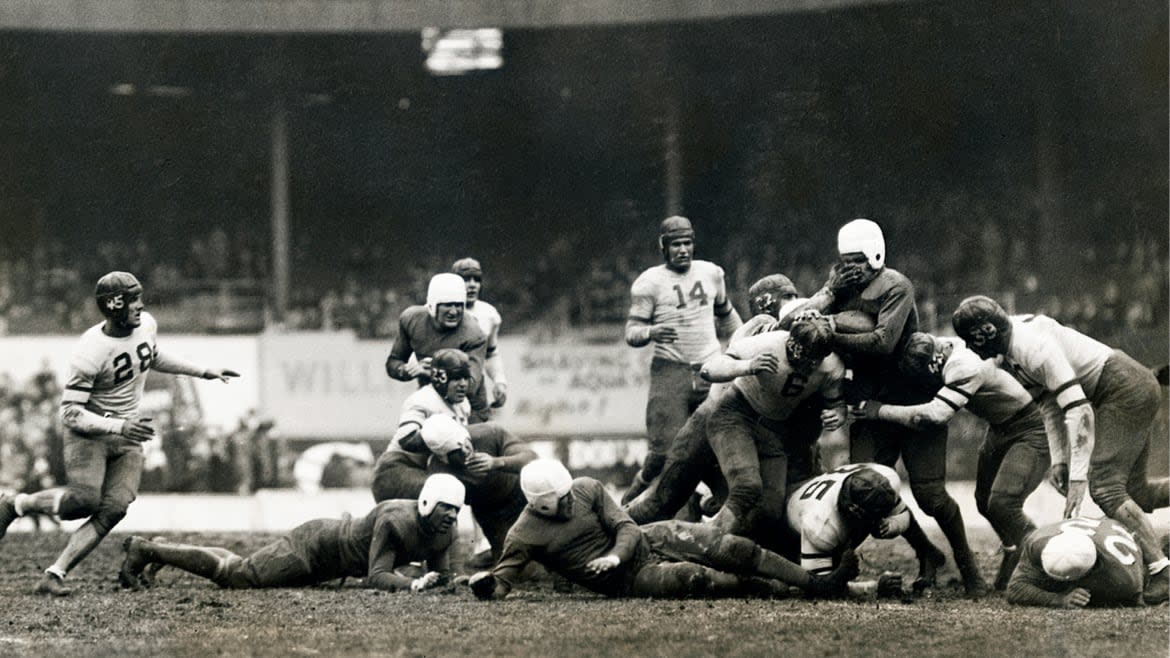

Built by convict laborers, Sanford Stadium opened on Oct. 12, 1929 in a game against mighty Yale, which was led by its quicksilver halfback, Albie Booth. My father and his buddy Dan Magill, unable to afford three-dollar tickets, slipped under a fence and spent the game snaking through the throng of 30,000, always on the lookout for an usher who might demand to see their tickets. Catfish Smith scored the first touchdown by falling on a blocked punt in the Yale end zone. He then kicked the extra point. He scored again on a pass reception. By halftime the Connecticut Yankees, dressed in blue woolen jerseys, were melting in the 90-degree heat of an Indian summer afternoon. Smith completed the scoring when he cornered Booth, eight inches shorter and 50 pounds lighter, and flattened him in the Yale end zone for a two-point safety. Booth popped up and barked, “That shit doesn’t go around here!” Smith, nose to nose, barked back, “Neither do you!” Dan Magill and my father had worked their way down close to the field by then, and Dan cried: “Richard, look! You see that? Catfish is jawing with Albie Booth!” The final score was Catfish Smith 15, Yale 0. It was, for better and for worse, the birth of big-time college football in the South. Georgia would eventually bring in a football coach named Wally Butts, who would win the school’s first national championship and help solidify the fervor of fans and the power of the alumni-dominated Georgia Athletic Association.

Georgia vs. Yale, the first game at Sanford Stadium, Oct. 12, 1929.

John, meanwhile, was left to wonder what the $360,000 spent on Sanford Stadium could have done for faculty salaries and health insurance and pensions, for new libraries, for a campus that was run on such a tight budget that everything from routine maintenance to stadium construction was performed by convict laborers. The university had made a Faustian bargain, as John saw it, and Goethe had taught him long ago that one day there would be hell to pay.

A half-century later, by weird happenstance, I got to watch John’s dark premonition come true. In 1983, with no qualifications other than a deep voice and a great face for radio, I talked my way into a job as a disc jockey at a Top-40 station in Savannah. As the new man, I was given the thankless graveyard shift, which meant I was on the air from midnight till 6 a.m., playing endless rotations of the current hits from Prince and ZZ Top and Michael Jackson’s Thriller album while the city around me slept. Since the station broadcast University of Georgia football games, my duties also included assembling each Saturday’s taped, hour-long pregame show. As an added bonus, I was ordered to travel up to the campus in Athens for the annual preseason Media Day.

It was an experience I’ll never forget. Georgia had won another national championship in 1980, and Bulldog running back Herschel Walker had been awarded the Heisman Trophy in 1982 before skipping his senior year and going to work for the New Jersey Generals of the fledgling United States Football League, a team that would soon be sold to New York real estate developer Donald Trump. When I arrived on the Athens campus for Media Day, there was an armada of TV trucks parked outside the athletic complex, bristling like giant insects with antennae and wires and satellite dishes. Nearby loomed Sanford Stadium, which, after four expansions, could now accommodate 82,000 fans. (Today it seats more than 92,000.) Inside the complex, an army of broadcasters, sportswriters and nobodies like myself bustled around, interviewing coaches and players. It was a preposterous dance. The interviewers approached their subjects with great deference, especially the star players and the coach, Vince Dooley, a guy with a gingery comb-over and machined teeth who looked like he belonged on a used-car lot. All utterances from such wise men were written down or tape-recorded or videotaped as though they were holy writ, soon to be disseminated to the waiting faithful in the farthest outposts of Bulldog Nation. It was amazing to watch grown men kowtow to mumbling teenage boys, even if those boys happened to be chiseled, 250-pound slabs of beef. The same question was on all lips: Will there be life after Herschel?

Eventually I broke away from the dance and noticed…the girls. Some were Black, most were blonde, all were impossibly glossy and fit, as though they’d been raised on a diet of yogurt, sunshine and Jane Fonda aerobics videos. Co-eds don’t look like this up North, I thought, remembering my college years in New England. These girls were lurking along the walls in sundresses, bouncing up and down—the word jiggling came to me—and I realized they were waiting impatiently for all the old men with the microphones and notebooks to get out of the way so they could get a shot at those beautiful slabs of beef, prime boyfriend material, maybe husband material, maybe even N.F.L. meal-ticket material. The air in that room was a hormonal cocktail, so potent, so thick, so musky that I was surprised those girls hadn’t already come out of their sundresses. All in due time, I told myself.

As I drove back home to Savannah that evening, I realized I had gotten an up-close glimpse of the big-time college football business model. It was built on an infantile news media feeding pap to infantile fans while the university raked in millions of dollars off the unpaid labor of pampered teenagers who, in more than a few cases, could barely read and write. The formula had it all: get the media to feed celebrity and sex to a die-hard audience, and you’ll wind up sitting on top of a very big pile of money.

Though I was unaware of it at the time, some people felt the pile was not nearly big enough. The University of Georgia had just joined forces with the University of Oklahoma to file a lawsuit seeking to end the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s monopoly on negotiating college football TV contracts. The NCAA had decreed that no team could appear on national television more than six times in two years, and it picked the games to broadcast regionally and nationally. The administrators and athletic directors at Georgia and Oklahoma understood that Catfish Smith and Wally Butts and their successors had bred a blue-ribbon cash cow. And now they were determined to be the ones to milk it.

The year after I attended Media Day, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 7-2 in favor of the plaintiffs, freeing schools to negotiate their own TV contracts. Today, CBS pays the Southeastern Conference $55 million a year to broadcast its football games. Under a new contract that takes effect in 2024, ESPN will begin paying the conference $300 million a year. That is some serious milk.

Three years after I attended that Media Day in Athens, the president of the University of Georgia resigned after the board of regents implicated him and Vince Dooley, who by then was athletic director as well as football coach, in a pattern of academic abuse in the admission and advancement of student-athletes. The abuse was brought to light by Jan Kemp, an English professor who had the temerity to complain when higher-ups intervened to give nine football players a passing grade for a remedial English course they had failed. The passing grades enabled the players to compete in the Sugar Bowl on New Year’s Day 1982. So, as it turned out, things had not progressed much in the nine decades since John began teaching remedial English to nearly illiterate country boys wearing their first pairs of shoes— only now a lot of money was at stake. For her trouble, Kemp was demoted, then fired. She sued the university, claiming she had been ousted because she had spoken out, a violation of her constitutional right to free speech. At trial, one of the university’s attorneys justified the favorable treatment of a hypothetical football player this way: “We may not make a university student out of him, but if we can teach him to read and write, maybe he can work at the post office rather than as a garbage man when he gets through with his athletic career.” Despite such shrewd lawyering, Kemp won the case and was awarded more than $1 million for lost wages, mental anguish and punitive damages. She was reinstated to her job.

If John had lived to see this circus, he would have been appalled but hardly surprised. This, he’d sensed way back in 1929, was where things were inevitably headed once “amateur” sports were turned into a gushing revenue stream. The university would be powerless to turn down the money, and the money would acquire the power to pervert the mission of the university. Yes, it was a deal with the devil, as John had predicted. A losing deal. It was also John’s idea of the American way: ruin a perfectly good thing by trying to turn it into money.

Excerpted from The Age of Astonishment: John Morris in the Miracle Century—From the Civil War to the Cold War by Bill Morris. Published by Pegasus Books. © Bill Morris. Reprinted with permission.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.