The Day Iron Ships Went to War

One hundred and fifty-nine years ago today in Virginia, on the second day of the Civil War Battle of Hampton Roads, something happened for the first time in the history of the world: Two ironclad ships fought each other. The Confederate CSS Virginia, a rebuilt version of the USS Merrimac, had participated in the battle’s first day and had its way against the wooden ships of the United States Navy. The USS Monitor, hastily dispatched from the Brooklyn Navy Yard, arrived just in time to join the battle on the second day. News of the two ironclads’ clash was carefully watched by naval observers from Europe. So many were interested not merely because of American naval ingenuity but also because the road to a clash of ironclad ships had been a long one with many entrants.

The Dawn of Iron and Steam

The idea of armoring ships was ancient, and gained serious attention from the dawn of muskets and cannons at sea. In the 16th and 17th centuries, as European warships grew increasingly large and heavily armed and their decks higher, it became common to use copper plating on sections of the hull. The challenge was technological: Nobody could design and manufacture a metal-hulled ship that would float. Everything below the waterline was wood.

One early example of armoring a warship, which attracted much local comment at the time, was the Korean “turtle ship.” Japan from 1592–98 launched a vast, bloody, ultimately unsuccessful invasion of Korea, eventually losing a third of its 158,000-man invasion force. One of the weapons the Koreans deployed to great effect against the Japanese navy was the turtle ship. No contemporary depiction survives, so there is some controversy over exactly how the turtle ship was designed, but it is commonly believed that the ship covered its deck with armor and spikes, less as a defense against cannon fire than against muskets and boarding raids. The turtle ships are thought to have been rowed galleys rather than sailing ships, thus enabling the deck to be covered without masts. Both Korea and Japan isolated themselves from war or commerce with the outside world for two-and-a-half centuries after 1600, so the turtle ship’s secrets were lost.

Iron-sided ships — whether wooden hulls clad in iron, or hulls made of iron — remained impractical so long as ships depended on wind to propel them. The advent of steam engines, first designed in the late 1700s and put into practical use in a paddle-wheel boat in 1807 by Robert Fulton, made it possible to build heavier ships. The first iron boats, built by the Laird shipyard in Liverpool, were steamers used in Ireland and Georgia. In 1832, the Lairds’ Alburkah became the first iron ship to make an ocean voyage, from Liverpool to West Africa. While steamboats came immediately to dominate river and harbor transport (making fortunes for men such as Cornelius Vanderbilt), it would be decades before they were seen as reliable ocean-going vessels. There were a variety of technical and economic reasons for this, including the cost and weight of the coal and the stability of boilers in a storm.

The great leap forward for iron warships came in 1841 with the British Nemesis. The projection of British power by sea far outstripped all other nations by the 1830s, and the need for a nation with a tiny army to maintain its overseas commerce and empire drove the British to be early adopters of both wooden and iron steamboats as tools of empire and war. The first use of steamboats in a military campaign came in the First Anglo–Burmese War in 1826. The British steamer was confined to towing and ferrying warships and moving troops rather than fighting, but the effect of what the Burmese called the “fire devil” on the war was decisive. The East India Company, the private corporation that ruled India, was the Lairds’ top customer, buying nearly half of their iron steamers before 1841. Iron arrived just in time: Britain had cut down much of its remaining forest to build the navies of the Napoleonic Wars.

With the outbreak of the First Opium War between Britain and China in 1837, the British had immediate naval superiority around coastal Chinese ports. To bring the war inland, however, required overcoming the vastly more numerous (if poorly equipped and motivated) Chinese army. The proponents of steamboats, led by Thomas Love Peacock, sprang into action. They convinced the aggressive foreign secretary, Lord Palmerston — the architect of the war — to deploy steam-powered gunboats to subdue the rivers that served as China’s commercial arteries. Gunboats were revolutionary: For the first time in human history, naval power could be projected upriver with speed and force. They would greatly extend the reach of European imperialism.

The British were surprised to find paddle wheels in use in China, which they arrogantly ascribed to the “Oriental” gift for imitation. But they had it backwards: The Chinese had been using paddle wheels (powered by hand cranks turned by slaves) since the twelfth century, and the first prototype steamboats in Britain in 1788 had actually taken the idea from descriptions of Chinese paddle wheels. But in the 1840s, the Chinese were still turning their wheels by hand.

Meanwhile, the Lairds were at work on a secret project: building six iron steam-powered gunboats. In March 1840, one of the six was ready: The Nemesis, a 184-foot iron-hulled paddle-wheel steamer with the world’s first watertight bulkheads. Much of the ship — deck, rudder, paddle wheel — was still wood, and the bridge was open to the air. The Nemesis became the first iron vessel to round the Cape of Good Hope, nearly sinking along the way. Only on January 7, 1841, was it finally sent into action in China, with devastating effect. A fleet of Chinese war junks was stationed upriver from Canton (now Guangzhou), in water too shallow for British sailing ships to enter. While the rest of the British fleet cut off their escape, the Nemesis steamed in and started launching Congreve rockets, swiftly destroying eleven junks. In an hour and a half, the Chinese suffered 280 dead and 462 wounded; the British did not lose a man. Complete naval superiority on the rivers would decide the war, shifting the balance of power in Asia in favor of the West for the rest of the century.

The next test came in Mexico in 1843. Texas was not the only Mexican state to secede in 1835–36; it was just the only one to succeed. The war conducted by Mexican president Antonio López de Santa Anna to put down the secessionists raised its own tensions in the south, where the province of Yucatán particularly resented having to send troops to fight the faraway Texans. In 1839, Yucatán seceded. When Santa Anna blockaded the peninsula, Yucatán hired Texan-crewed and commanded ships from the Texas navy, which sailed against the orders of Texas president Sam Houston. Santa Anna’s navy responded by deploying the 183-foot ironclad Guadalupe, also built by the Lairds in Liverpool. Set to sea with a British captain and crew, the ship flew the Union Jack. Unfortunately for the Mexicans, the British captain died of yellow fever the night before the battle, and most of his experienced gunners were deathly ill of the disease. The Texans were unable to dent the Guadalupe, but they smashed one of its wooden paddle wheels and killed 47 of the crew. Santa Anna was thwarted by the Texans once again; Yucatán would return to the Mexican fold, but on its own terms.

The Arms Race

Even with the development of fast-sailing clipper ships, the Age of Sail’s days were numbered. The British Royal Navy launched its last great sailing ship in 1848. The death-knell of both sail and wooden walls was sounded at the Battle of Sinop in November 1853. The Russian and Ottoman Empires went to war in October 1853, as they had done several times before, over disputes both religious and territorial. Russia’s invasion of Ottoman territory along the Danube (modern-day Romania) alarmed the neighboring Austrian Empire, but did not bring other powers into the war. Neither did the presence of the British and French fleets near Constantinople (now Istanbul), placed there to deter Russia from sailing into the Mediterranean.

On November 30, 1853, the Russian Black Sea fleet staged a surprise raid on the Turkish fleet at Sinop, on the northern Turkish coast, with the aim of cutting off supplies to the Turkish army in the Caucasus. It was the first time explosive shells were used in naval combat, and they swiftly demonstrated that wooden ships could no longer stand up to naval bombardment, especially when fired by ships that had put on steam to close for combat. In an hour and a half, 2,700 Turkish sailors were killed, and the Turkish fleet was destroyed. Russia gained complete naval supremacy over the Black Sea. That, Britain and France would not tolerate. They declared war in early 1854, turning the Russo–Turkish conflict into what became the Crimean War, the bloodiest European conflict between 1815 and 1914.

The governments of Britain and France both immediately recognized that their navies had become obsolete. Napoleon III ordered the building of armor-plated floating batteries, but these still had to be towed. Russia, behind the times, launched the world’s largest warship, the American-made wood-hulled frigate General Admiral in 1858; it had to be retired from service by 1873. An ironclad-warship arms race began, and the French won, laying down La Gloire, the first ironclad capital ship, in November 1859. It would take 13 months before the British caught up, launching the Warrior in December 1860. The arms race drove tensions between Britain and France, still nominally allies, to a fever pitch. Paranoia about a French invasion led to the construction of a series of coastal forts along the southern British coast after 1860, labeled “Palmerston’s follies” after the man now prime minister. Only when France was defeated by Prussia in 1870–71 would it become clear that Napoleon III’s massive investment in an ironclad fleet was a grave strategic misallocation of resources that could have been spent on his army.

The Race Comes to America

Americans were slow to engage in the competition among the European powers, but the outbreak of the Civil War gave new urgency to sea power. The Union’s “Anaconda Plan” strategy depended upon a naval blockade of the Confederacy’s thousands of miles of coastline, most of which was bottled up by early 1862. Gunboats patrolled the rivers, playing a crucial role in Ulysses S. Grant’s capture of Forts Henry and Donelson in February, 1862. Blockade-running became a Confederate priority, but the Holy Grail of Confederate naval strategy was to force open a hole in the blockade. Nowhere was that more militarily crucial than in Chesapeake Bay, which controlled access both to Washington, D.C., and to the Confederate capital at Richmond. The bay’s outlet was protected by the Union-controlled Fortress Monroe.

On April 20, 1861, a week after the surrender of Fort Sumter, the commander of the Gosport Navy Yard in Norfolk, Va., (located where the James River flows into Chesapeake Bay) concluded that his position was indefensible and torched the place. The Confederates, moving in, found the hull of the burned Merrimac intact. Under orders from Confederate Navy secretary Stephen Mallory, they began rebuilding it as a new weapon, rolling railroad ties flat into iron plating. Unlike the Nemesis, constructed halfway around the world from its war zone in the years before the telegraph, the building of a Confederate ironclad was no secret. Gideon Welles, the former newspaperman serving as Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of the navy, set the Union to developing its own ironclad ship in Brooklyn. Both sides knew they were in a race against time.

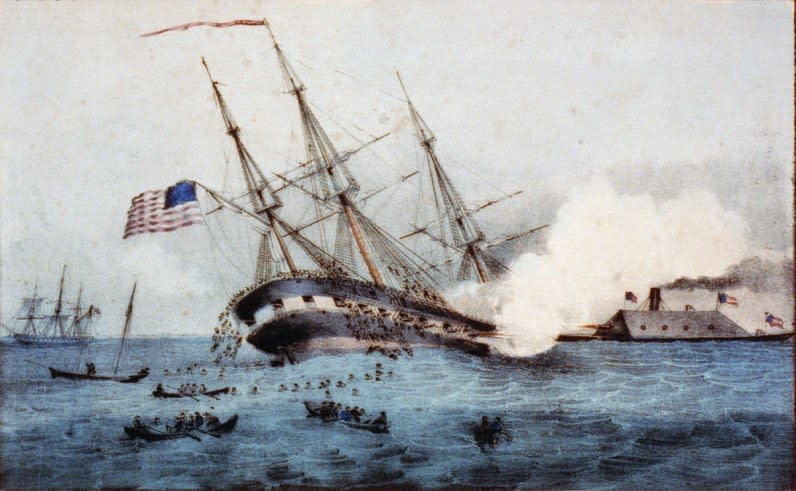

The Confederates won, by one day. On March 8, 1862, the Virginia steamed into the harbor against three Union sailing ships and two steamers. Two-hundred-and-seventy-five feet long, shaped like a shoebox with rows of guns protruding on each side and no masts, the Virginia was an evolution of traditional ship design. Its success was almost as dramatic as that of the Nemesis. The Virginia sank the sailing ship Cumberland, finishing it off by ramming it. Everything old is new again: Ramming was a favored tactic of rowed galleys and triremes in the ancient world, but sailing ships could not generate the closing speed to ram. Under fire, the sailing ship Congress surrendered. A steam frigate, the Minnesota, ran aground, and the Virginia’s captain planned to finish it off the next morning. The Union shells seemed to bounce right off the Virginia. Two hundred and forty Union sailors were killed; the Navy would not lose two ships in the same day again until Pearl Harbor.

Lincoln held a cabinet meeting the next morning, at which a stack of alarmed telegrams were reviewed. This was still early in the war, before Robert E. Lee assumed command of the army of Northern Virginia, before Shiloh introduced mass-casualty battles and opened the Mississippi valley to conquest. Things had all been going the Union’s way since the Confederate victory at Bull Run the prior July. The Union’s leadership was still inexperienced with setbacks. Edwin Stanton, just two months into his tenure as Secretary of War, flew into a panic, warning that the Virginia would terrorize the East Coast. It was, Stanton said, “Not unlikely, we shall have a shell or a cannonball from one of her guns in the White House before we leave this room.” He wanted ships sunk to block the Potomac.

Fortunately, Mary Louvestre, a freed slave working as a seamstress for one of the engineers on the Virginia, had rushed to Washington in secret in February to tell Welles that the ship was almost ready. Armed with Louvestre’s intelligence, Welles ordered the Monitor to sea without even a commission or a crew. It had to be towed for the ocean voyage, and like the Nemesis, almost sank on the way. It arrived just too late to join the action on March 8.

Unlike the jerry-rigged Virginia, the Monitor was designed from scratch to be a revolutionary ironclad warship. It was the work of John Ericsson, a brilliant naval innovator who was confident enough in his design to agree to build the ship at his own financial risk; Welles would pay him only if it worked. The Union war effort featured many immigrants, but Ericsson was unusual because he came from Sweden, a country that banned emigration until 1840. Not until the Swedish famine of 1867–69 would Swedes begin to come to America in significant numbers.

Ericsson’s design incorporated one of his prior inventions: the undersea screw propeller. The screw was superior in a number of ways to the paddle wheel, but never more so than in combat, where a shot to the paddle wheel could swiftly disable a warship. Ericsson also added a brand-new element: the rotating turret, which would not only revolutionize naval design but would, much later, be essential to the construction of tanks. The 179-foot ship’s “cheese-box on a platter” layout looked nothing like any ship anyone had seen before. The Confederates were stunned at its appearance at Hampton Roads.

The duel of the Monitor and the Virginia, commencing early on the morning of March 9, was inconclusive. While both ended up inflicting more damage than was immediately apparent, neither could disable the other in an engagement that featured two hours of heavy fire. The Monitor temporarily withdrew after its captain was briefly blinded by a hit to the wheelhouse, and the Virginia fled to avoid being beached at low tide. Strategically, however, the battle was a major Union victory, securing control of Hampton Roads and the outlet of Chesapeake Bay for the rest of the war.

Reports of the battle confirmed what naval reformers had been arguing since Sinop. The London Times, referencing the Warrior and Britain’s other new ironclad, wrote:

Whereas we had available for immediate purposes one hundred and forty-nine first-class warships, we now have two. . . . There is not now a ship in the English navy apart from these two that it would not be madness to trust to an engagement with that little Monitor.

Eager to get more firsthand reports, the Royal Navy dispatched a ship to loiter in the area to watch the rematch; the French navy sent two ships to do the same. But the Virginia never fought again. It sailed with a supporting force of six ships on April 11, but the Monitor would not come out to give battle, and the Confederates would not risk the open sea.

On May 9, after George McClellan had landed a Union army on the peninsula, Lincoln came to Fortress Monroe to visit the front and was stunned to discover that McClellan had no plan in place to attack the now-surrounded Norfolk naval base. Lincoln was still deferential to his generals at this stage of the war, but leaving the Confederate naval super-weapon at large was too much to tolerate. Lincoln personally commandeered a tugboat and went ashore himself on enemy soil to scout for a good place for McClellan to land troops, an unprecedented bit of hands-on presidential daring in a war zone. Two days later, with Union troops closing in, the Virginia was scuttled by its own crew a second time, this time for good. The Monitor sank in a storm at the end of 1862.

Ironclad ships would quickly become the order of the day. The Monitor proved inexpensive to build and replicate, and would form a key part of the Union navy, which laid down 58 ironclad ships before the war was over. The Confederates built 21 ironclads, mainly modeled on the Virginia, but to less effect. Analysis of the Russian program for building ironclads, begun in 1863, revealed that it cost three times as much to refit a wooden ship with iron as it did to build a new Monitor. The key elements of Ericsson’s ship design would form the basis of most of Western naval construction for the next century, widening the gulf between Western and non-Western sea power until Japan caught up. In 1865, Spain’s Numancia became the first ironclad warship to cross the ocean, reaching the west coast of South America in time to participate in a war against Peru and Chile.

The last ride of the wooden-walled navy came in 1866, in the Battle of Lissa in the Austro–Prussian War. Italy, fighting on the Prussian side with a newly minted fleet of twelve ironclads and 17 wooden ships in support, faced off against seven ironclad and eleven wooden Austrian ships, the first-ever battle of ironclads in the open sea. Confident of victory, the Italians even brought along Ippolito Caffi, a gifted Venetian painter, to capture the action from the Italian flagship. Italy, however, was plagued by internal rivalry among its commanders, poor coordination (the Italians shifted their flag at the last minute, unbeknownst to the ships looking to it for signals), and poor gunnery, with one key broadside fired without shot having been loaded. The Austrians rammed and sank two of the Italian ironclads, sending Caffi and the crew of the former flagship to the bottom in two minutes. The wooden Kaiser rammed another Italian ship, hitting its target with such force that its masthead was embedded in the other ship’s deck. It would be the last time that ramming was used in a major naval engagement; the Virginia’s revival of the tactic was quickly outpaced by advances in naval gunnery.

Since that day at Hampton Roads, navies have never been the same.