A day of life and death in a COVID hotspot: Jacksonville

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Shortly before noon on Friday, Jacquelyn Graham-Townes leaned over a white casket containing another person who ended up in her care because of the coronavirus.

The funeral director at James Graham Mortuary wore a black dress, pearls, a sparkly mask and disposable blue gloves. She picked up a brush and lightly applied makeup to Willie Woodard’s forehead, cheeks, nose. Not too much, she said. Just the right amount to have him look his best for his family at the viewing that afternoon.

As the funeral director worked, she echoed what doctors and nurses at local hospitals have been saying for weeks: This is worse than anything Jacksonville experienced in 2020.

Last year the mortuary handled funeral arrangements for about five COVID-19 deaths.

“Now I’ll do that in a few days,” she said. “I’ve done four in one day. It’s like the floodgates broke open.”

Florida is awash in COVID-19 cases, and Duval County is struggling to keep its head above water.

Grim reality: Duval County becomes nation's COVID-19 hot spot for hospitalizations

Nate Monroe: The view from a Jacksonville ICU, Florida's COVID-19 hot zone

A look inside school: How one Duval middle school is coping with COVID

The 1,486 Floridians reported dead the week ending Friday is almost 15 percent higher than the previous worst week, in January. (The state hasn't released county figures for months now.) Hospitalizations as of Saturday were almost 70% higher than last winter's peak.

It was all on display in Jacksonville on Friday. The frustration and exhaustion of those dealing with the dead and dying. The anxiety of the sick, hoping to stay out of the hospital.

It 'seems like a different disease'

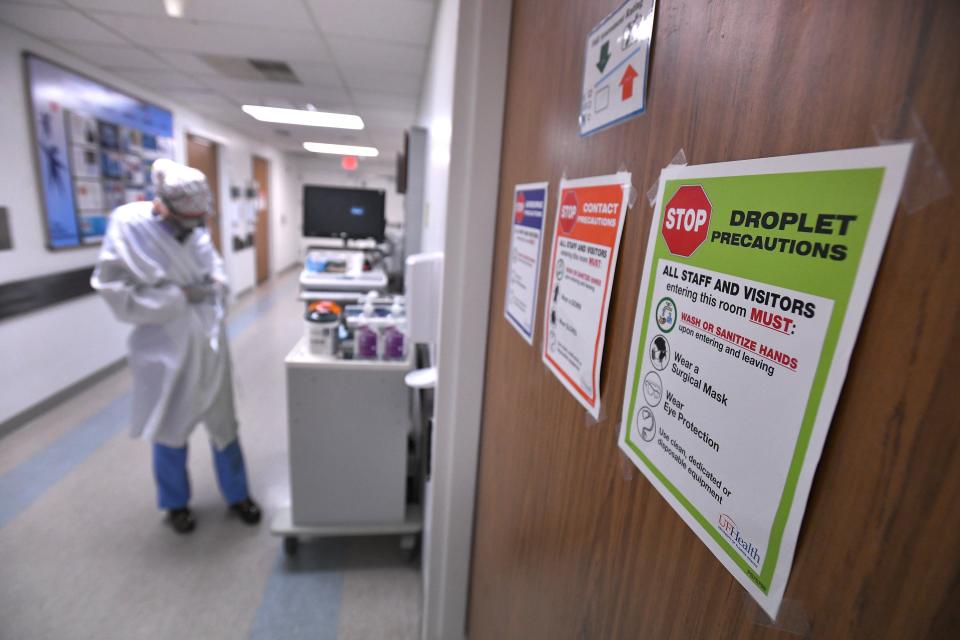

In a glass-paneled room at UF Health Jacksonville, a patient’s chest heaved. Four nurses and a respiratory therapist tended to the diabetic woman in her 50s, who couldn’t breathe on her own.

As a last resort, they put her on a lung bypass machine. That was five and a half weeks ago.

A nurse rested a hand on the patient’s shoulder. Trauma surgeon Dr. Marie Crandall, one of eight clinicians crammed in the room at one point, stepped into the hall.

“She’s — she’s not going to make it, unfortunately,” Crandall said. “A family member is in there now. We do allow one at a time at end of life — which might be now-ish.”

'That light did turn out to be a train': UF Health Jacksonville staff face surge in COVID

'Gut-wrenching': Children making up more of Jacksonville's surge of COVID hospitalizations

Such moments have become common at Jacksonville's trauma center, a safety-net hospital that serves many uninsured and low-income patients.

Such moments have become common at UF Health. More than 70 people have died there of COVID-19 this month alone. Like almost all of the hospital's critically ill patients, all were unvaccinated.

“It makes me angry. It makes me sad," Crandall said. "I don’t understand why people don’t believe in science.”

Space at the University of Florida teaching hospital is at crisis levels by CDC standards. Inside the cramped emergency department, some patients are parked on gurneys and hospital beds wherever there is room.

Medical teams, in a perpetual state of triage, rushed in and out of rooms and huddled to brainstorm at the central nursing station, high-pitched alarms wailing in their ears.

Upstairs in COVID-19 unit Seven North, a wing that until recently was used for tuberculosis patients, 29 unvaccinated patients were hospitalized Friday. Each nurse handled six patients instead of the usual two or three.

Akira Rivera-Perez, 24, was one of those nurses.

“It’s been very overwhelming. It’s been traumatizing,” she said. “You see patients just go down so quickly. We only have so much we can do. And sometimes, that’s not enough.”

It’s Rivera-Perez’s first nursing job. She started during last winter’s surge. “Even though that one was bad, this one is worse. Way worse,” she said. “It almost seems like a different disease.”

A few days earlier, a patient was moved to her floor to make space in the ICU. Puerto Rican, like her, he reminded her of her grandpa. She sat and chatted with him in Spanish. But he quickly deteriorated, unable to eat or breathe. She had to wheel him back.

“I try not to make that connection. But it’s tough, you know. You care about these people, and you want them to be good,” she said. “I love my patients.”

Rivera-Perez recalled a woman whose family couldn't visit because they had COVID-19. “She was just alone at the end,” Rivera-Perez said.

Pastor Michael Girard, a hospital chaplain and youth leader, recently counseled a mom who lost her daughter to the virus. Two days later, she died, too.

Chaplain Cynthia Simpson said a mother, father and son died days apart, as another son struggled in the ICU on a ventilator. “No one wanted to be vaccinated. No one wearing a mask. And they had this big family get-together,” Simpson said.

Sometimes Rivera-Perez ducks into the supply room to cry. She gives herself five minutes or until she gets another call — whichever comes first.

“I’m so tired. Tired of seeing people get sicker, not better,” she said. “I just wish people would get the vaccine if they could.”

Some seek treatment even without testing positive

![Family members provide shade with a sheet for a loved one as they waited on the sidewalk outside the main library for the Regeneron clinic inside to open Friday morning. About 50 people were in line outside the downtown Jacksonville, Florida main library Friday, August 20, 2021 as they waited for the 9 am opening of the clinic inside that gives Regeneron's Monoclonal Antibody treatment to mitigate the symptoms of COVID-19. [Bob Self/Florida Times-Union]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/.aTFFo_wLcG30vdKbyrJeA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTgzNQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/the-florida-times-union/adac528a46c689082a6b9623862de040)

In the fast-rising morning heat, the faces of 50 people waiting outside the library in downtown Jacksonville showed the anxiety running through the city. The line of people, some using walkers and others in wheelchairs, stretched down the block by the time the doors opened.

Inside, a conference room has been converted into a clinic to administer the Regeneron antibody cocktail.

Monoclonal antibodies such as Regeneron's — cloned versions of immune cells that successfully fought off COVID-19 — have been shown to be 70% effective at preventing hospitalization and death when given to people within seven days of developing symptoms. They do not work when given later.

The people lining up hoped it would keep them out of the hospital, even if it meant four injections in different parts of their bodies and a one-hour wait afterward for any side effects.

More on Regeneron: Gov. DeSantis unveils Jacksonville site for getting monoclonal treatment of COVID infections

Behind the shot: Jacksonville Regeneron clinic photo ‘doesn’t convey ... pain' of COVID-19 patients

Nate Monroe: In Jacksonville, DeSantis' first Regeneron site off to slow, embarrassing start

Upon entering the library, patients were greeted by an odd sign: "Please do not sit or lay on the floor." It said anyone needing immediate medical attention should contact a medical staff member. It was spurred by a photo that went viral showing two people lying in discomfort on the carpeted floor while waiting to get Regeneron. The company managing the site brought in more wheelchairs and seating.

Jacksonville was the first of 17 Florida cities where Gov. Ron DeSantis opened sites for Regeneron this month.

Sue Chauncey, 64, of Middleburg didn’t need much convincing. Two days after testing positive for COVID-19, she made the 30-mile trip to downtown Jacksonville. She compared the injections to bee stings and said she’s optimistic the treatment will work.

“My doctor said I needed to go get it done because I was very sick,” she said.

Julia McClendon, 66, of Jacksonville had tested positive 10 days earlier and had been getting better. Her fever and headaches had gone away, but she still had an upset stomach.

Her husband Howard McLendon gave a one-word answer when asked why he’s confident in the treatment: “DeSantis.”

The governor’s endorsement has spread the word about Regeneron, but even with hospitals in Jacksonville at the breaking point, this site hasn't hit its daily capacity of 300 doses.

On Aug. 17, the first day at the library, 97 doses were administered. By Sunday, it had risen to 224. Friday, three days later, it doubled to 194 doses. It rose to 224 doses on Sunday at the clinic, which operates seven days a week.

Former President Donald Trump credited Regeneron for his quick recovery from COVID-19.

The treatment at state-run sites is available to people 12 and older, regardless of whether they’ve been vaccinated or not. No prescription or physician referral is needed. Patients don’t even have to provide proof of a positive COVID-19 test, as long as they’re in a high-risk category and were in close contact with someone who has COVID-19, according to a spokeswoman for DeSantis.

Charles J. Miller, a Jacksonville resident, got the Regeneron injections Friday before he had gotten his test results. He said he hadn’t been feeling well and didn’t want to wait any longer to get Regeneron.

Leaving the library two hours later, he said it was worth it. "If it works,” he said, “it's better than lying in a hospital bed.”

"Too much death"

Shortly before the country found itself in the grips of the pandemic, Graham-Townes' father made her manager of the mortuary he started in 1987 on a triangular block where Moncrief Road and Myrtle Avenue cross.

While every service was affected by the coronavirus – limited gathering sizes, masks, live-streamed services – it didn't cause most of the deaths she handled.

More: A look back at 2020 in Jacksonville, through the eyes of a last responder

That's not the case now. In one week, Graham-Townes handled 14 deaths from COVID-19. The youngest was 21 years old, the age of her oldest child. The common denominator: None were vaccinated.

That was also true of the man lying in a white casket Friday morning.

It was a relatively slow day, just two viewings. One was for a 1-month-old girl, unrelated to COVID-19. The other was for Willie Woodard.

He was 49 years old, a longtime employee of the Bacardi bottling plant in Jacksonville.

Darlene Woodward arrived shortly before 3 p.m. She wore a white dress and, on a bracelet, the two rings she gave her husband when they got married. One was for being her spouse. The other was for being her best friend.

They met 11 years ago. It was karaoke night at Applebee’s. She went with a friend who needed some cheering up. When one patron started being disrespectful to them, this large man stepped in. And he literally swept her off her feet.

Between tears, she laughed as she recalled dancing with him that night, realizing at one point her feet weren’t touching the ground.

He worked 21 years at Bacardi, as a rum processor. He loved his job, she said. Even more than that, he loved dancing. And more than anything, he loved his family and his wife.

They celebrated their eighth anniversary last month. A few days later, they both started to feel sick. They thought it was just a cold.

“It didn’t click,” she said, sobbing. “It just didn’t click.”

He kept insisting he was fine. By the time it did click, after his breathing had gotten worse and worse, they took him to UF Health North. He died there, exactly three months before his 50th birthday.

A week later family members walked into the viewing room at James Graham Mortuary. “I Give Myself Away,” by William McDowell, played faintly. Nine chairs were spaced out in the room.

As they entered, they passed a sign that has been hanging there since last spring: “Although we all long for the coming day when this sign isn’t necessary … PLEASE CONTINUE TO REFRAIN FROM HUGGING AND HANDSHAKING.”

Eight months ago, at the end of 2020, Graham-Townes was upbeat and optimistic about what 2021 had in store for all of us. The 42-year-old funeral director talked about plans with her husband and their two children, a son headed to Florida State and a daughter at Riverside High. She figured vaccines would become available and that would be the turning point. She didn’t expect so many people to resist getting them.

Now the pandemic isn’t just filling up Jacksonville area hospitals, taking a toll on doctors and nurses overwhelmed by this wave. It’s reached the point where it’s taking a toll on the last responders, the funeral directors like Graham-Townes.

Death is a part of the job. It has been part of her family’s jobs for generations. One of her grandfathers was a funeral director in Alabama. One of her uncles started a funeral business in Jacksonville in the 1970s. Her father opened his own funeral home in 1987.

But this has been different. As she prepared Willie Woodward’s body for the viewing, Graham-Townes pointed to the back of the mortuary, where two more victims of coronavirus awaited her.

She said it’s reached a point where she’s started to avoid going on Facebook, knowing what she’ll find on her feed there.

“It’s too much,” she said. “Too much death.”

Contributing: Karen Weintraub, Mike Stucka, USA TODAY

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: COVID-19 surge hits Jacksonville hard in hospitalizations, deaths