It’s a new day in old Overtown. Miami’s original Black district is making a comeback

On a recent sunny Friday evening in Overtown, Chris Norwood swings open the door to the Ward Rooming House, a restored 1925 stucco building built by a Bahamian immigrant — one of the few left from the neighborhood’s long run as the epicenter of Miami’s Black community — and now converted into an art gallery.

Classic Miami soul music plays in the background as Norwood greets visitors, while a couple of assistants bustle about to ready the bar for Hampton Art Lovers’ gallery night. On view: an exhibit of large-scale photos of pandemic life in Overtown and last summer’s local George Floyd protests by Miami photographer and DJ Rahsaan “Fly Guy” Alexander.

Across the street, the parking lot and the tables are filling fast at Red Rooster, celebrity chef Marcus Samuelsson’s soul-food-meets-Caribbean-Miami version of his original Harlem restaurant of the same name. The Miami-New York connection is no coincidence: Before a steep decline measured in decades, Overtown was known far and wide as the “Harlem of the South” and “Little Broadway,” for its cultural vibrancy and its dynamic music clubs.

Four blocks away, tiny Lil Greenhouse Grill is packing them in with a “neo-soul food” menu so successful the restaurant will be moving into a larger, newly built home nearby. And a block from that new location, next to an Einstein’s Bagels brought to Overtown by Miami Heat veteran and hometown booster Udonis Haslem, workers are building out what may be the clearest sign that things are truly, finally looking up in the neighborhood: A Publix.

It’s a new day in the heart of old Overtown, the neighborhood whose original inhabitants — the Bahamian immigrants and Southern Blacks who provided the labor for Henry Flagler’s railroad and Royal Palm Hotel — literally built Miami.

Confined by racial segregation to the other side of the tracks they laid down, residents of Colored Town — as it was first known — created a thriving enclave of their own before highway construction sundered the neighborhood in the 1960s., draining it of economic vitality and much of its population while ushering in decades of neglect and disinvestment.

Now it looks like Overtown’s time has come again.

Slowly and painstakingly, a proud neighborhood best known by outsiders for blight and impoverishment is showing rousing signs of new life. After years of foundering public and private revitalization schemes and broken government promises, a new spate of commercial, cultural and housing ventures has taken firm root in Overtown.

The initiatives have been seeded by the incessant wave of redevelopment enveloping adjacent downtown Miami and Biscayne Boulevard, which are generating tens of millions of dollars in tax revenue for Overtown improvements. They’re also driven by keen interest in recovering the historic neighborhood by a young generation of Black Miamians with roots in Overtown and others, like Norwood, who have adopted the cause as their own.

“If you’re a Black Miamian, chances are you have a connection to Overtown or Coconut Grove, whether you had a grandfather there or grew up there yourself. Giving them a reason to come back has been one of the joys of having this gallery,” said Norwood, a lawyer by training and an art collector and curator by avocation who has shown museum-quality work by Black artists at the Ward house.

“Very quickly what I’ve seen is Overtown is becoming a place to be. We have a couple of great magnets. Now we have to fill in the gaps. People are overcoming their fear and hesitation when they think a place is cool, and that’s what’s happening in Overtown,” he said. “But I don’t look at this as redevelopment, I look at it as a reclamation.”

PLAN IN ACTION

What’s going on in Overtown is not happenstance.

Buoyed by a surge in tax revenue from new luxury residential and mixed-use towers along Biscayne Boulevard and in the adjacent Park West neighborhood, a once-maligned city of Miami anti-poverty agency is now pumping millions into Overtown projects, laying the groundwork for an economic and social revival its leaders say is just getting started.

The Southeast Overtown/Park West Community Redevelopment Agency, funded by a portion of property taxes from new development within its boundaries, has lent key support to new businesses like Red Rooster, Lil Greenhouse and Hampton Art Lovers, while providing financing for the renovation and construction of thousands of apartments and townhomes across Overtown.

The high-rise apartment buildings now sprouting across the historic core of Overtown, along with announced plans by the CRA and a private developer for a massive mixed-use project anchored by a Target and Aldi, have raised fears among some residents of potential gentrification and the erasure of the neighborhood’s Black history and identity.

But CRA director Cornelius “Neil” Shiver contends the agency’s strategy strikes a smarter balance.

Where 1960s urban renewal meant the demolition of scores of residential and commercial buildings (many of them historic Overtown landmarks) as well as displacement of residents, he argues the neighborhood may today succeed where others have failed — allowing residents to stay and enjoy the fruits of revitalization.

Shiver said the CRA is doing so by capitalizing on the flow of revenue and developers’ newfound interest in Overtown to enhance residents’ quality of life and the neighborhood’s role as a center of Black life and culture. At the same time, it’s attracting new residents of all races and incomes and the kind of substantial private investment Overtown has sorely lacked for decades.

“You can never regain the glory days,” Shiver said. “But we want to bring that vigor back.”

The CRA, governed by the Miami commission, has provided partial financing and land — it’s been one of the biggest landholders in Overtown for decades — to attract private developers. In return, the developers must agree to set aside significant chunks of apartments in their new towers for renters with very low to moderate incomes.

The Target project, for instance, promises 578 apartments for low-income elderly as well as 1,000 permanent jobs, with Overtown residents getting first dibs. At the newest, The Celeste, set to open in June, 80 of 360 apartments are reserved for low-income renters.

Because virtually all the new development is on vacant land cleared decades ago, no one is physically or directly displaced, Shiver notes.

Meanwhile, apartments renting for market rates will go to people with disposable income to support local restaurants and businesses, boosting Overtown’s overall prosperity, Shiver said. Some locally owned shops are already popping up to cater to visitors and residents, like Suite 110 Urbanwear on Third Avenue, which carries an extensive collection of Overtown- and Black-themed apparel.

The CRA has also sunk tens of millions in the past dozen years into extensive renovations and repairs of hundreds of apartments and townhomes in Overtown, where much of the housing stock has been in a state of advanced deterioration. The work includes full renovations of “concrete monsters” — the open, two-story apartment buildings typical of private housing in the neighborhood — and ongoing gut rehabs of the 432 townhomes that make up the three sections of Town Park Plaza and Town Park Village, a Miami-Dade County initiative combining condos, co-ops and subsidized rentals that had fallen into near-ruin. Town Park’s Section 8 renters and owners will be able to stay in their homes.

The clear improvement across the neighborhood is little short of “amazing,” one longtime resident said.

“The CRA has been a godsend,” said Dana Milson, 52, an Overtown native and president of the Town Park Village co-op, where she lives with her husband and children. “There were always promises before, but nothing materialized. But in the past few years, the promises have been kept.”

“We can only dream of what could have been, but now, actually seeing it — the restaurants, the art, the new housing — it’s really exciting.”

In a separate section of Northeast Overtown, the Omni Community Redevelopment Agency is following a similar approach, helping finance full renovations of older apartment buildings in exchange for low rents for tenants.

The slate of current allocation of CRA money, totaling $109 million, will produce 4,099 new or fully renovated units of housing across Overtown, the agency says.

Another big CRA recruit: the parent company of the Brightline rail line, which erected an office, retail and parking building on the Overtown side of the tracks, a couple of blocks from its new train station and office and residential complex on the downtown Miami side of the corridor.

The 3 Miami Central building, wrapped in large Overtown-themed murals and aluminum friezes by African-American Miami artist Robert McKnight, houses Brightline corporate headquarters, offices for ViacomCBS, and the Einstein’s and Publix, which has not yet announced an opening date.

“We think we have the right strategy,” Shiver said. “ No one from Overtown would have to move or be displaced as a result of the transformation that’s taking place. Overtown is a success story compared to other places.”

RESIDENTS OF ALL SHADES

To be sure, a revitalized Overtown’s population will look a lot different from the Black enclave of yore. At its peak, neighborhood population exceeded 30,000 people. Today it’s barely 8,000, and Miami-Dade’s demographics mean many new residents will be white and Hispanic.

That doesn’t bother Brian Aikens and Monica Rolle, an Overtown couple who just welcomed their first baby. They’re embracing the changes in the neighborhood, from the new high-rises to new residents of different shades, all of which they say has made Overtown more hopeful, far friendlier and safer than before.

“It’s cool. It’s way better,” said Rolle, 29, whose father is Bahamian and who grew up in Overtown. “It’s filling with new people of all kinds, and everyone is getting along very well.”

Since January, Aikens has been working as a line cook at Red Rooster, and loving it.

“It’s fantastic, man,” said Aikens, 32, who’s been working in restaurants for more than a decade. “You have people come from everywhere, all nationalities. You got famous rappers, Dwyane Wade — everybody comes to Overtown to that restaurant.

Aikens is one of about 85 people employed at the restaurant, many recruited in Overtown. As pandemic restrictions ease, Red Rooster will boost its workforce to 120, said partner Derek Fleming. The restaurant also hired locals to work on renovation of its historic building, once home to a pool hall run by legendary Overtown club manager and music promoter Clyde Killens.

The connection to both the history and people of Overtown, Fleming said, has been as critical to its popularity as the food by Samuelsson, born in Ethiopia and adopted by Swedish parents, and executive chef Tristan Epps, who is of Trinidadian extraction. On any given weekend day, when it serves both brunch and dinner, the restaurant attracts 500 to 600 people, Fleming said.

More than a restaurant, Red Rooster has sought to become a locus of Overtown and Black Miami life, and not just for the food. Harking back to Overtown’s musical history, It also offers a nightly menu of live soul, R&B and jazz or DJs spinning funk, dance and hip-hop, plus a Sunday Gospel brunch.

“What’s beautiful about it is, we get a lot of people who now live in Overtown or people who had moved or left, and they’re coming back,” Fleming said. “The physical experience, the vibe you get at Red Rooster, is what people are drawn to, and it’s distinctive. They’re excited about coming to a historical place with yummy food.”

Soul and southern cooking has fueled a rising Overtown food scene that includes Lil Greenhouse, which drew a visit from no less than Oprah Winfrey, and longtime neighborhood landmarks Jackson Soul Food and Two Guys. In the midst of the pandemic, unable to serve guests breakfast indoors, the new Copper Door B&B, just west of Interstate 95 from central Overtown, created a soul-food breakfast and lunch window pop-up named Rosie’s, which has garnered rave reviews.

The dining spots have been joined by Groovin’ Bean, a corner coffeehouse offering fair-trade brews, beignets on special order, other baked goods and breakfast and lunch five blocks down Third Avenue from Lil Greenhouse. The cafe turns into a lounge Friday evenings, with music, tapas, beer and wine.

And, in a neighborhood that hasn’t had a place for visitors to stay since famed hotels like the Sir John and its neighbor the Mary Elizabeth were torn down decades ago, there are now two, both of them geared to cultural or “heritage” tourism: The Copper Door B&B, housed in a renovated 1940s building, and the boutique Dunns and Josephine Hotel, which occupies an abutting pair of resplendently restored small hotels from 1938 and 1947.

For Stephanie van Vark, a marketing entrepreneur who bought a condo in Overtown’s Poinciana Village with her husband in 1999 after moving from her native Georgia, the changes in the neighborhood have been a long time coming. She regrets only that so much of authentic Overtown was lost in the intervening decades.

“We came to Overtown with the idea that it was historically a prosperous African-American place, and the idea that it would one day be that again,” she said, adding: “It’s been a bit of a struggle.”

Three years ago, to help ensure inclusiveness and historical awareness in whatever Overtown becomes, van Vark launched GoingOvertown, an online directory, newsletter and community-building site. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, she offered walking tours of Overtown; the site now includes a self-guided walking tour and an events calendar.

“I see the progress,” van Vark said. “I absolutely believe there has to be investment made. But I struggle with the idea that in this city that means eradicating what was there and starting over, instead of enhancing what’s there and trying to advance the situation for those who are here. How do we find a nice balance?”

MANY EXCLUDED

To be sure, there are many in Overtown who still feel they’re excluded from the dream of prosperity and worry sooner or later they will be pushed out.

Overtown includes some of Miami’s poorest residents, with a median household income of just $23,000 and more than a third of the population living under the poverty level, according to an analysis of Census Bureau data by point2homes.com. The drug trade still flourishes on some back-street blocks.

In spite of extensive renovations by the CRA and islands of newer housing built by nonprofit groups over the years, many Overtown residents must do with decrepit housing. In central Overtown as in surrounding residential areas, extensive swaths of vacant lots persist. The new buildings and hot spots are in many cases scattered blocks from one another.

The pandemic only exacerbated the inequities, prompting long lines for food drop-offs. Many in the neighborhood work in the hospitality industry and lost their jobs.

Debbie Roberts, Overtown born and raised, said she would love to see a return to the days of close-knit community, when Black doctors and dentists not only had offices down the street from her home, but also lived in the neighborhood. But she doesn’t think that’s going to happen.

“We’re getting the short end of the stick all the time,” Roberts, 59, a family support specialist, said. “Those prices in Red Rooster don’t fit the people in Overtown who’re living paycheck to paycheck. I don’t have no problem with building Overtown up, but let the people in Overtown be involved. Show them that what used to be can still be.”

Still looming forbiddingly over the neighborhood, Roberts noted, are the elevated expressways that helped speed its ruin. Several dozen homeless people, many of them from Overtown, take shelter in tents under the I-95 overpass at Northwest 10th and 11th Streets.

In what Roberts and others see as a repeat of the blighting influence of the highways on the neighborhood, the Florida Department of Transportation is now rebuilding the Interstate 395 overpass that cuts west to east through Overtown to take motorists to Miami Beach.

FDOT officials contend the new span will be much better than the old: The new expressway project will reconnect several Overtown streets severed by the old highway’s concrete embankments. The roadway span will be higher, with thinner columns, and split in two, allowing light and air to reach the ground — in contrast to the oppressively low overpasses that now spread gloom and blight across their path. Plans call for a 55-acre expanse of parks and public amenities under the span, but skeptics remain leery of FDOT’s promises. Some say the massive new expressway, at a cost of over $800 million, remains an unwelcome intrusion on Overtown.

“If you live in Overtown, if you live in Allapattah, if you live in Liberty City, you don’t need an expressway to go downtown or go to the Beach for that matter,” said Miami Commissioner Jeffrey Watson, whose district includes Overtown.

Backers of some of the new Overtown ventures, however, seem determined to become a part of the community fabric. Some were quick to respond when the COVID-19 pandemic struck, providing meals, food and even shelter.

The influx of new residents, visitors and businesses has helped in other critical ways, supporters say.

One of the neighborhood’s most persistent scourges, crime, is way down. Miami police statistics show crimes in every category have dropped dramatically in Overtown over the past decade.

That there is still an Overtown to come back to and renew, supporters say, is a tribute to residents’ unusual pride, strong community bonds and sense of responsibility. Organizations such as the Black Archives fought to preserve historic Overtown landmarks like the Lyric Theatre, which the group now owns and runs, and the clapboard home of Dana Dorsey, one of the first Black millionaires in the South, now a small museum across the street from the Ward Rooming House.

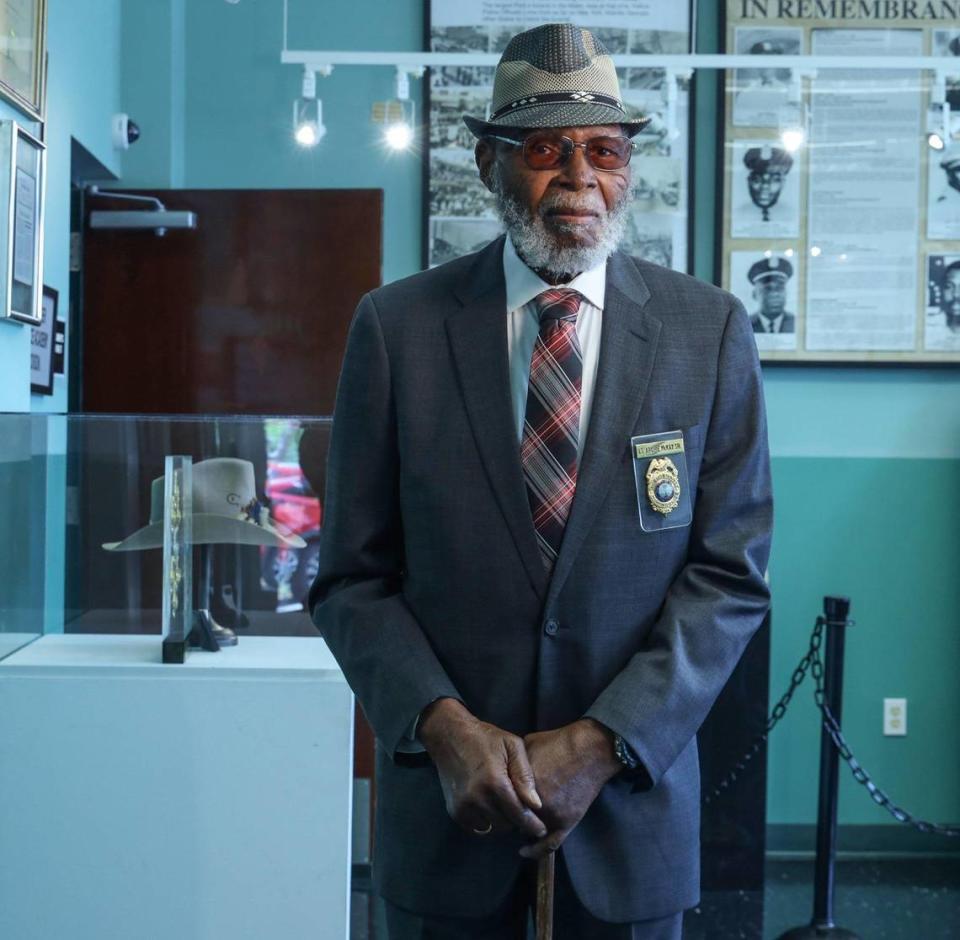

After years of pleas from activists, the city renovated a collapsing Overtown police station that housed Miami’s first Black officers and judges.

Today the Black Police Precinct and Museum, though underfunded, houses historic exhibits and hosts tours and events just a couple of blocks from resurgent Third Avenue.

Believers in a renewed Overtown say cultural and entertainment venues like the Lyric, which hosts popular monthly amateur performance and comedy nights, may provide the key to consolidating its revival by bringing back the life and music that helped make it great — like the long-vanished Harlem Square Club, where soul singer Sam Cooke recorded a live album in 1963 that is today widely regarded as one of the greatest ever.

Developer Michael Simkins, who has been quietly acquiring land in Overtown for years, is working with the CRA on a comprehensive plan for an entertainment district that would reproduce that long-ago heyday. Simkins, an investor in Red Rooster, envisions nightclubs and restaurants in restored historic buildings and new mixed-use towers rising on what are now mostly vacant lots in Overtown’s heart.

To spark interest, he’s backing The Urban, an open-air, Wynwood Yard-like venture by Overtown-born entrepreneur and philanthropist Keon Williams. From Thursday through Sunday, it offers food trucks and cargo containers serving culinary bites and craft cocktails and a performance space that’s already hosted hip-hop shows by such stars as 50 Cent and Lil Wayne.

“Authenticity and the history of the area do matter, because Overtown did have such a rich history of entertainment,” Simkins said.

To van Vark and other Overtown residents — ‘Towners in the local lingo — one key to preserving the neighborhood’s continuity will lie in persuading those who have left, in particular those who went off to college and didn’t return, to come back home to Overtown. And that means the developers and the new entrepreneurs must make good on promises to house, hire, train and promote ‘Towners and come up with creative ways to keep that culture alive, she said.

“We need to draw real money, create jobs, identity,” van Vark said. “But still I have some big questions: What if what’s here gets erased despite the best intentions? I don’t know what will happen once we fully build out the neighborhood. Is it going to be great? Is it going to be enhancement or just gentrification?

“My husband and I just imagine the day we can go to a theatrical production, and then go to Red Rooster or another little place with a bar or a wine shop. It’s a good dream.”