Deacon uncovers names of Black Catholics buried in unmarked graves at Louisville cemetery

St. Louis Cemetery in Louisville's Tyler Park neighborhood serves as the final resting place for nearly 50,000 Catholics spread across 43 acres dotted with ornate sculptures and monoliths.

Family plots are scattered about the land, and the names of some of Louisville's earliest and most prominent Catholics engraved into obelisks. Among them is James Rudd, a wealthy businessman and politician who owned more than four dozen slaves before Emancipation.

One of those former slaves led Deacon Ned Berghausen to the cemetery, and he found that during Mary Narcissa Frederick's nearly 100 years of life, she was "loaned" by Rudd to Bishop Benedict Joseph Flaget, the first Roman Catholic bishop of Louisville.

She was buried in the plot of the Rudd family she served for decades, who had accepted her as payment for a $10,000 debt. But if you were looking, you wouldn't know she or her husband were buried there.

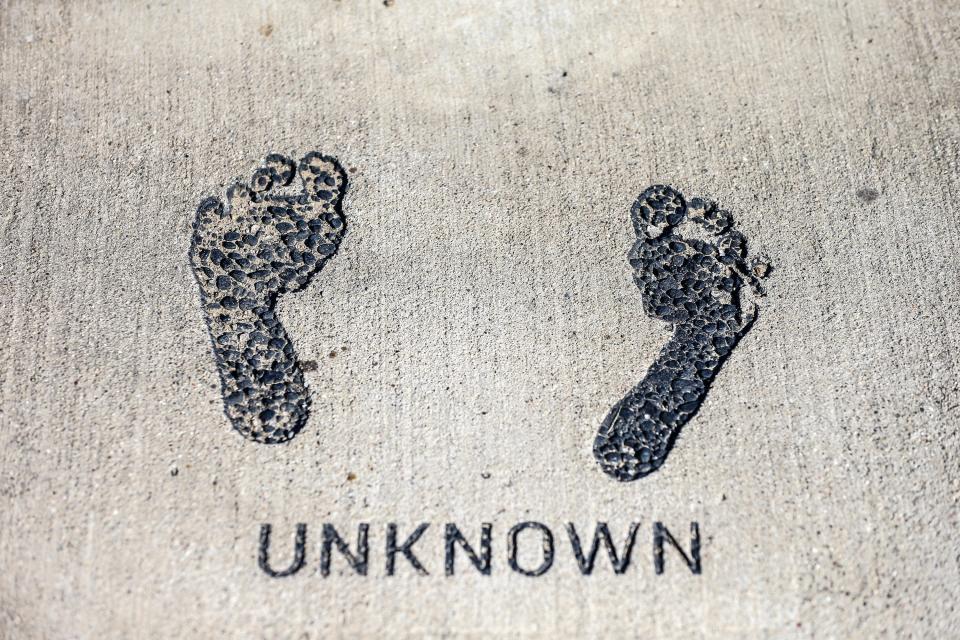

Berghausen, who serves at St. Agnes Church on Newburg Road, found that the Fredericks were interred in unmarked graves, and that in the back right-hand corner of the cemetery, nearest Mid-City Mall, was the site of more unmarked Black Catholic graves.

After scouring the cemetery’s records, he found there were actually 1,630 people buried in what otherwise looks like an unused piece of land.

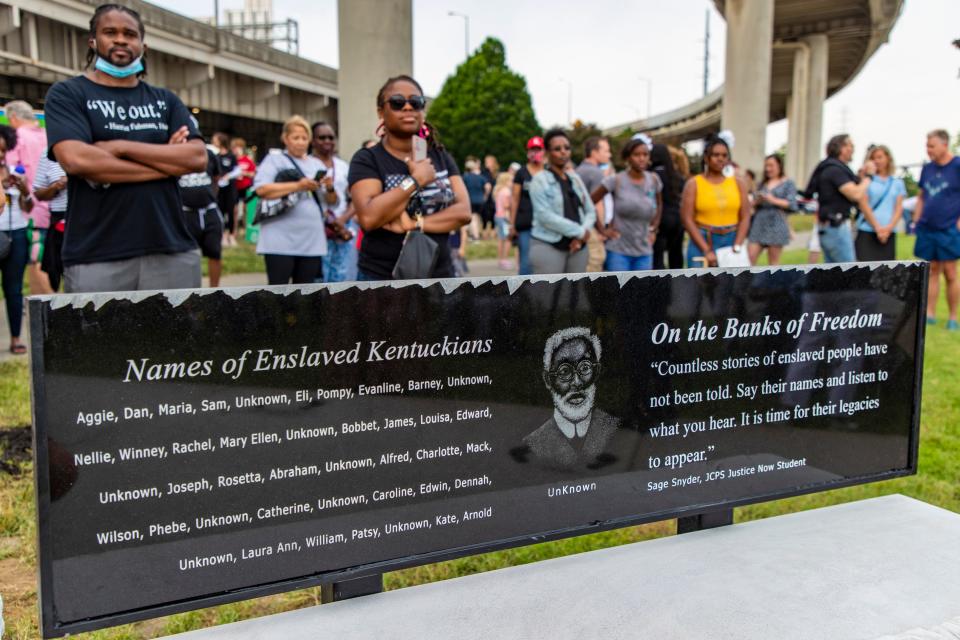

Around the same time, he met Hannah Drake, co-founder of the (Un)Known Project, and the two have been working together to “restore some of the dignity that was denied" to the people buried there when they were alive, Berghausen said.

Drake, Berghausen tied together by slavery

Drake and Berghausen’s path to one another would have been unlikely a few years back, but it was each of their familial connections to slavery that ultimately led them to one another.

Drake, a nationally recognized poet and a prominent local activist, has made finding information about Kentucky’s history of slavery her full-time mission. A Black woman, her skin told her she has an undeniable connection to slavery, though much of her family history had been untraceable until recently.

She launched the (Un)Known Project in 2021, not long after seeing the names of Kentucky’s roughly 170 known lynching victims memorialized at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. Of those, eight are listed as “unknown.”

That sparked something inside her, Drake said, a resounding question of how many more people have existed whose names are currently lost to history.

“It’s not that they’re unknown, it’s just that someone has the information, it is somewhere and it hasn’t been released publicly,” she decided.

For Berghausen, finding himself on this path was far less predictable - he started digging into his family’s history years ago, thinking he’d find some “positive things … like a lot of people do.” But instead he discovered some of his Kentucky ancestors were slaveowners.

At the time “I really wasn’t ready to grapple with it,” he said. But in the aftermath of Breonna Taylor’s killing by police, and while at home with newborn triplets, Berghausen started revisiting that family history.

“I felt a stirring in 2020,” he said. “I felt an awakening about the injustice of racism in our community, and finding my own family’s connection to slavery made that really real and personal to me in a way that it hadn’t before, and I felt that I had to do something.”

For Drake, that decision is what The (Un)Known Project is all about.

“We are intertwined and our history is not separate from each other,” she said.

Acknowledging this connection to slavery, she said, “is not an accusatory indictment of your family. It is history, and none of us can change it.”

In the stories and documents passed down from generation to generation, there could be the names of former slaves that have yet to be uncovered.

“Not saying their name because you are ashamed of what your family did … you can’t grow in shame, you grow in truth,” Drake said.

Saying their names

Beyond reckoning with his personal connection to slavery, Berghausen has dug into the Roman Catholic church’s connection to it.

He found the obituary of Mary Frederick, which highlighted that she was “loaned” to Flaget.

The obituary listed her accomplishments, including that she was a founding member of the first Black Catholic parish in Louisville and had served as a sponsor for numerous baptisms and confirmations of enslaved people.

The obituary, published in the Kentucky Irish American newspaper, said that “for an ex-slave she was remarkably well read, and some of those who knew her well declare 'her skin was black, but her heart and soul were white.'”

It also gave a nod to the family that had owned her, whom she “did not desert” after being freed, and the service they put on after her death.

Rudd’s son, John Rudd, said Mary Frederick was worth “every cent, and more, too, of that $10,000” that his father forgave for her.

This rattled Berghausen, he said, feeling the obituary presented her as the “stereotype of a happy slave who is loyal to her enslavers,” and the Rudds as “noble people whose best interests were for their enslaved people instead of for profiting off their labors and their bodies.”

When he went to find her grave, he noticed the Rudds didn’t give her a headstone. When he went to dig further into the Catholic church’s role in slavery in Kentucky, he found that information hadn’t been recorded as thoroughly as other pieces of history - despite finding it was “really widespread.”

Berghausen, who teaches at Assumption High School, also considered the juxtaposition between the church’s stance on slavery when it first came to Kentucky to where it is today - with the Rev. Shelton J. Febre - the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Louisville’s first Black archbishop - appointed in 2022.

“Knowing part of that history, to move from bishops who enslaved people to having a descendant of enslaved people (to lead) was symbolic and powerful to see,” Berghausen said.

When he first asked for more details regarding the unmarked graves at St. Louis Cemetery, he was given a list of 690 names - less than half the names he’d eventually uncover. Buried between 1867 and 1937, these people were either former slaves or were the first to second generation born into freedom.

Berghausen said he spent 13 months looking through records listing all of the people buried there, noting each person who was labeled as "colored" and then creating family trees for each of the 1,630 on Ancestry.com. He found 35 of the Black Catholics were veterans of the Civil War or World War I, and he helped organize an event last November to honor their service.

Now during Black History Month, Berghausen and Drake have partnered with the Center for Interfaith Relations on an event to read each of the more than 1,600 names, “to do something to right something I know is wrong in history,” Drake said.

“It means a lot to say these people are here,” she said. “It means a lot because everybody has the right to say ‘I was here and I existed.’”

For the Catholic church, the event will be “a symbolic way to remember and honor these deceased Black Catholics whose graves are unmarked,” Fabre told The Courier Journal.

“In this way we proclaim the intrinsic value of their human life and affirm the human dignity of each one of them, and indeed the human dignity of every person,” he said. “We pray for their eternal rest and peace in the Lord. We also pray that this encourages us to listen with open hearts to the stories of our brothers and sisters who are racially different from us. In this way, we can combat racism and foster greater healing and reconciliation among people of different races and cultures.”

Contact Krista Johnson at kjohnson3@gannett.com.

IF YOU WANT TO GO:

WHAT: Remembrance: Reading of the Names will honor the lives of 1,630 Black people buried in unmarked graves

WHEN: Saturday, Feb. 24, 2 to 3:30 p.m.

WHERE: St. Louis Cemetery, 1167 Barret Ave.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Black Catholics buried in Louisville cemetery identified by deacon