How the deadly Long Beach earthquake in 1933 propelled California's seismic safety rules

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A whole lot more than a big piece of Southern California landscape got shaken up in the space of 10 seconds on that March evening 90 years ago.

One month to the day after the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, California’s Legislature and governor, acting with a speed born of panic and voters’ fury, put into law the Field Act, which ordered rigid construction codes as well as inspections for public schools.

Why the rush?

Some 120 people died from the March 10 quake — the deadliest ever in Southern California, its fatalities second only to 1906 San Francisco quake.

Yet this quake has been called a “lucky one.” Luckily, it struck at 5.54 p.m. on a Friday, when most people were home for dinner, or heading there. Three hours earlier, and thousands of students would have been killed or injured within the walls of the 230 schools that collapsed, were damaged or rendered too dangerous to enter.

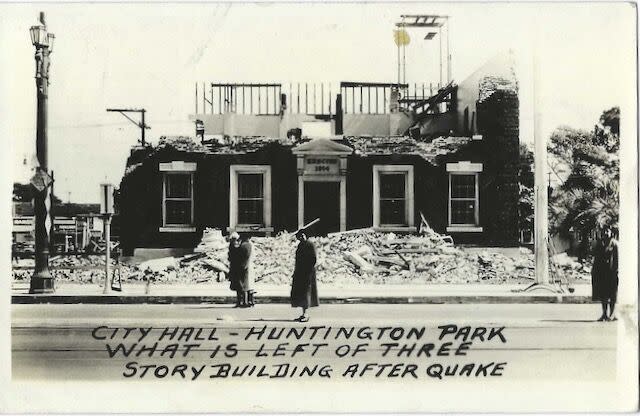

Thousands more public buildings — city halls, hospitals, theaters, libraries — and 20,000 houses from Newport Beach and Santa Ana to most of south Los Angeles County were leveled or seriously banged around.

In short order, Caltech’s president, Robert A. Millikan, was tapped to head up a technical committee to look into construction failures. He wrote in its summary three months later that in cities where the earthquake was most intense, damage to schools was severe and widespread: “Auditoriums collapsed, walls were thrown down, and the very exits to safety were piled high with debris which, a few moments before, had been heavy parts of towers and ornamental entrances. It is sufficient to suggest the terrible consequences, had the same earthquake occurred a few hours earlier.”

The Field Act was a striking new kind of law in a laissez-faire state. In time it was joined by more laws such as the Garrison and Greene acts — the first extending rigid codes to existing schools, not just new ones, and the other saying “we really, really mean it” — and by local regulations to keep public and private buildings from becoming deathtraps. Compliance was still lackadaisical into the 1960s, but in the 1971 Sylmar quake, schools that were built strictly to the Field Act codes had virtually no damage apart from banged-up light fixtures and knocked-over furniture.

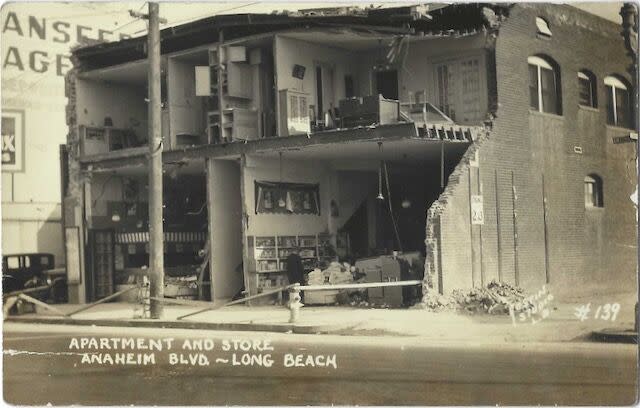

Far and away, most of the buildings that tumbled down in 1933 were of brick. The piles of tumbledown bricks on Long Beach streets took laborious weeks to clear away. Into the 1980s, many California cities were still having to require that their existing brick buildings be seismically retrofitted — and in some cases not following their own rules.

In 1933, most of the 120 dead, including a Long Beach fireman, were killed by these falling bricks and by unreinforced masonry.

All over Long Beach, walls fell away and left the buildings as open and exposed as dollhouses. At one Long Beach hospital, patients were carted onto the lawn after the hospital’s front wall collapsed. Five firemen were trapped when their main building’s front facade caved in.

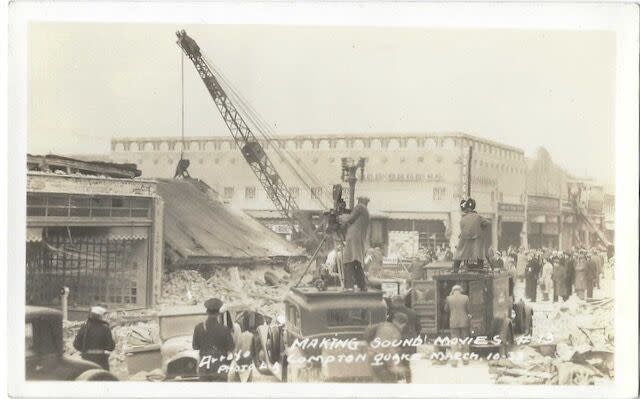

The U.S. Navy, with a formidable presence off Long Beach, sent 2,000 uniformed men ashore to patrol the streets and stop looters. The Pope sent his condolences. The Times-Universal Newsreel shot thousands of feet of film of the destruction.

Tens of thousands of people abandoned their homes. They slept on their own lawns or in parks, and in the cold March air, some wound up as pneumonia cases in the already overfull hospitals. Scores of Long Beach families drove into the hills south of Monterey Park to sleep in the open. A circus tent was set up to shelter them, and the American Legion began cooking meals for them. Rumors of a tidal wave sent people scrambling to higher ground. March Field, the military base in Riverside County, sent a rolling field kitchen with six cooks. The Los Angeles Milk Arbitration Board donated 11,200 quarts of milk to families left homeless in Compton, Long Beach, and Huntington Park.

Seconds before the ground began heaving, a 15-year-old Long Beach girl named Bea Criswell was getting dressed in her upstairs bedroom, sulking at having to go out to dinner with her parents, and saying to herself, “Please, Lord, do something so that I don’t have to go out to dinner!” For years thereafter, she felt that the quake was somehow her fault.

The magnitude is now calculated at 6.4, but the Richter scale had yet to be created. Instead, seismologists relied on a Roman-numeral-based Mercalli scale that depended on subjective assessments like how much objects were damaged and how people reacted.

About a year before the Long Beach quake, the Carnegie seismological lab in Pasadena had gotten money for a first-ever catalogue of Southern California quakes. In the hours and days after the quake, the lab’s head seismologist, Harry O. Wood, and an up-and-comer named Charles Richter headed out to Long Beach to check the seismic data. “I packed my portable instruments and gathered a team to monitor the shocks. Some of them went on for quite a while,” Richter told The Times on the quake’s 50th anniversary.

“The 1925 Santa Barbara quake got people to start talking about building codes,” said seismologist Lucy Jones, founder and chief scientist for the Dr. Lucy Jones Center for Science and Society, “but it was the 1933 quake that got us there.” The 1933 quake engendered the first rules requiring that buildings be bolted to foundations — something not adopted by every jurisdiction until 1960, she said.

Then, what emerged after the Long Beach quake was “the whole philosophy that there’s a role for government to keep you from building a building that will kill people — that really came out of that quake.”

The first map of the San Andreas fault came after the 1906 San Francisco quake. The Long Beach quake made people realize “earthquakes aren’t one-offs,” she explained. ”They’re a feature of California.” The 1933 quake, centered offshore from Huntington Beach, brought to light the existence of the Newport-Inglewood strike-slip fault, and a new awareness “that there’s more than one fault here, that there wasn’t just a San Andreas fault but a seismic system … that expanded our image of what we had to worry about,” Jones said.

In 2016, a pair of U.S. Geological Survey seismologists who had studied old oil-drilling records suggested in a publication that four earthquakes in Southern California’s coastal oil region in the first third of the 20th century — including Long Beach’s — might have been triggered by incessant oil extraction. I asked Jones about that.

“It’s not general consensus at this point yet. It’s almost impossible to sit here in the 21st century and look back and see what impact the drilling had,” Jones said.

“It was really clear that the oil extraction all around Long Beach was doing a lot of damage. Long Beach was sinking by meters,” she pointed out. “And some time in the 1940s, in Signal Hill, there was the collapse of the roof of an oil reservoir [where] they’d pulled so much out.” Thereafter, she pointed out, California required that “if you took fluid out you had to put fluid back in — a net-zero fluid extraction process.” Moreover, “there’s ample proof of the Newport-Inglewood fault before people were here.”

Two years after the Long Beach earthquake, Richter published his and colleague and mentor Beno Gutenberg’s research and the idea of a numerical scale to assess earthquake “magnitude.” The scale’s objective, base-10 logarithmic system caught on, and although it’s been superseded, people still attach his name to the scale. In years past, people sometimes showed up at Caltech asking to see this famous scale of his.

Richter was quite the character. His family moved here when he was 7 years old, and he felt his first quake tremor at age 10. He kept a seismograph in the living room of his Altadena house and answered reporters’ calls at any hour of the night. He did not drive, and was a devoted backpacker and a vegetarian. He was also a nudist — the genteel synonym back then was “naturist.”

His scientific files he left to Caltech, but his personal journals, books, home movies, notes, stamp collection, and letters filled floor-to-ceiling bookcases bolted in place in his nephew’s house in Granada Hills.

In 1994, eight years after Richter died, the whole collection became nothing more than ashes and mud after a fire at the house next door jumped to the nephew’s house.

The fire was triggered by the Northridge earthquake.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.