Deadly pathogens can hitch a ride on ocean microplastics, raising alarm bells

A novel experiment in a veterinary lab found deadly pathogens could be catching a ride on microplastics washing out to sea, concentrating the bugs and potentially putting humans and animals like sea otters, seals and dolphins at risk.

The pathogens, toxoplasma gondii, cryptosporidium parvum and giardia enterica, end up in waterways when feces from infected animals contaminate the water.

In the study, published this week in the journal Scientific Reports, scientists at the University of California, Davis showed microplastics can provide a new way for these microorganisms to concentrate near coastlines and travel deep into the sea.

"It raises alarm bells," said Cara Field, a veterinarian and medical director at the Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, California, who was not involved in the study. "If nasty protozoans are sticking to them, is that an alternative route of infection for us or for other animals?"

The pathogens are taking advantage of new "plastic habitat," and the study raises concerns about the public and environmental health consequences, said Peter Ross, also unaffiliated with the research and a senior scientist at the Raincoast Conservation Foundation, which works in coastal British Columbia, Canada.

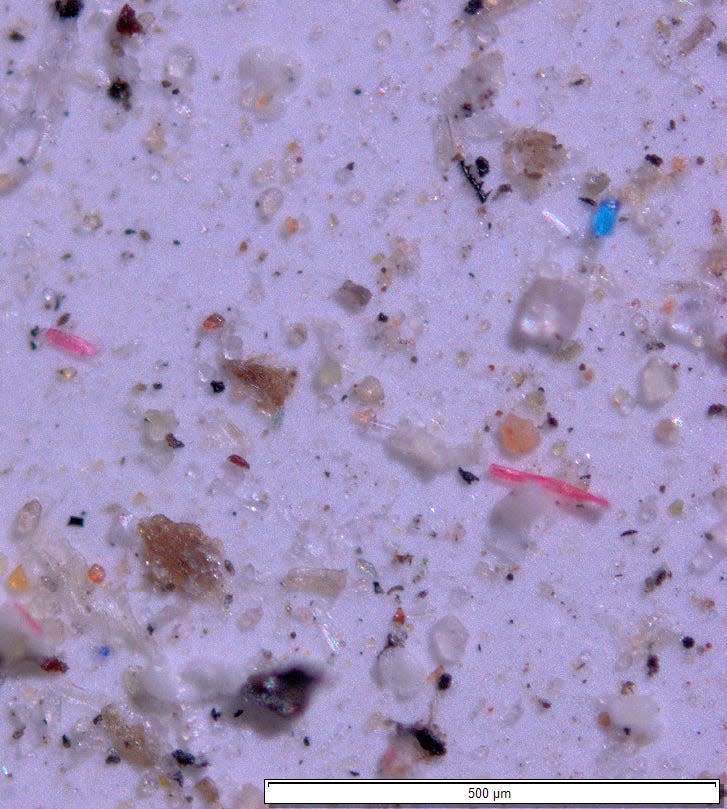

Microplastics are tiny plastic particles smaller than 5 millimeters, the size of a grain of rice or smaller. They include broken-down plastic trash that ends up in the ocean, microbeads found in some cosmetics such as exfoliants and cleansers, and microfibers from the lint of synthetic clothing.

They are a growing problem in the world's oceans and waterways. It's estimated that tens of thousands of tons of microplastics pollute global waters. The particles have been found in marine species as diverse as oysters and mussels, sea turtles, beluga whales and fur seals.

The UC Davis researchers set up experiments in the lab to see if the three pathogens could associate with microplastics in seawater. To their surprise, they could and did.

The microplastics acted “like a huge fly trap that’s swinging back and forth in the water, collecting things that are suspended in the water, and pathogens are one of them,” said Karen Shapiro, the UC Davis veterinarian who led the stud.

The researchers' experiments found the pathogens physically accumulated on the microplastic surface, a process called bioaccumulation. So many of the parasites got stuck to the plastic that they carried two to three times more of them than the surrounding seawater.

“I would never have dreamed of this," said Shapiro. "I would never have thought of plastic impacting the infectious diseases I study.”

It's too soon to know if microplastics have led to significant changes in the transmission of pathogens are transmitted but the issue certainly warrants more research, said Erin Lipp, a marine biologist at the University of Georgia and an expert on waterborne disease transmission.

It started with poop

The UC Davis researchers started out looking at how natural ocean transmission processes might affect disease transmission.

“Basically, what happens when poop ends up in the sea?” Shapiro said.

They initially began with toxoplasma gondii, a parasite that infects mammals, most commonly cats. In humans it’s most dangerous to pregnant people because it can cause blindness and brain damage in a developing baby.

More than half of the sea otters that live along California’s coast are now infected with the parasite, infections the team proved in 2019 are mostly coming from feral domestic cats living in coastal watersheds.

“That triggered our next question: What if this happens in a non-natural way?” Shapiro said.

The three pathogens they studied are all dangerous and can be deadly.

Cryptosporidium parvum, "crypto" and giardia enterica can cause gastrointestinal disease that can be deadly in children and the immunocompromised.

The parasite toxoplasma gondii can hide for years in cysts in human muscle and brain tissue, reactivating years later if the person becomes immunocompromised and potentially killing them.

It's also known to cause mortality in endangered marine mammals including sea otters, Hector's dolphins and Hawaiian monk seals.

Microplastics could be a route of exposure that hasn't been considered before, Field said.

"We know how the monk seals and the harbor seals are getting it," she said. "We think it's through fish, but what if it's a different mechanism involving microplastic? This raises an intriguing question we want to try to answer."

None of the pathogens can reproduce in seawater, but they can survive there for weeks to months and still be infectious.

“They’re not something that likes being out in nature," Shapiro said. "They’re just waiting for the next human or animal to ingest them so they can reproduce.”

The researchers are experimenting to see if the pathogens that get stuck in the tiny plastic bits are more likely to be ingested by oysters.

There's no indication ingesting seawater or consuming mollusks or fish that have ingested the pathogens is in any way dangerous to humans, but more research is needed, Shapiro said.

"Who would have thought when we were realizing that plastics were ending up in the ocean that they might affect infectious disease transmission?" she said.

One concern is these pathogen-infested microplastics might float long distances on the sea surface and infect species far from shore. They also could sink, possibly concentrating them on or near the sea floor, where filter-feeding marine species might ingest them.

It’s not yet known if this new potential disease vector is affecting species that live in the oceans, Shapiro cautioned.

“We’re saying that the problem of plastic pollution could have a pretty important effect on disease transmission that we need to start paying attention to,” she said.

Understanding the process could be key to helping in the rescue and rehabilitation work done by Field's staff at the Marine Mammal Center.

"If we can figure out how it happens, then we can figure out how to stop it," she said.

While more research is done, Shapiro advises Americans to keep microplastics out of the world's oceans. The Environmental Protection Agency and other groups offer these steps:

Wash clothing in cold water using shorter cycles to reduce microfiber shedding.

Use fewer disposable plastic products such as water bottles, plastic cutlery, straws and coffee-cup lids.

Drink from reusable water bottles or even just a glass and water from the faucet.

Recycle all plastic that can be recycled.

Dispose of trash properly so it doesn't end up in waterways.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: UC Davis researchers find pathogens can spread on ocean microplastics