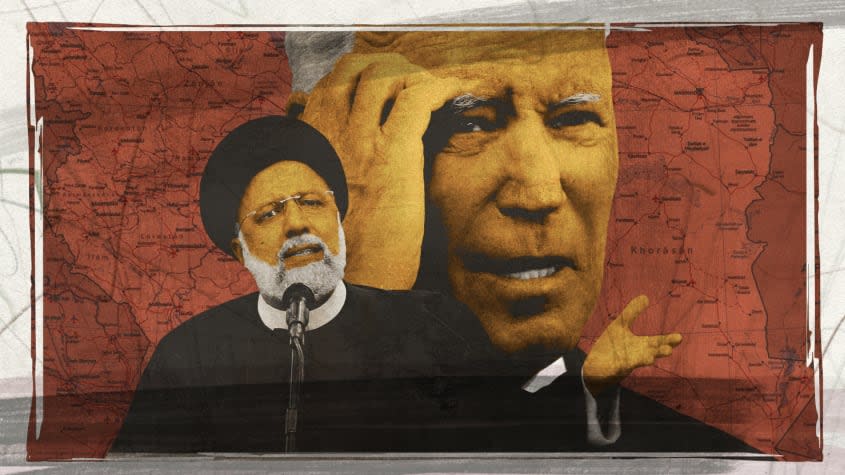

A new deal for Iran and the U.S.?

During the 2020 presidential campaign, Democratic nominee Joe Biden repeatedly promised to get the U.S. back into a renegotiated nuclear agreement with Iran, after former President Donald Trump withdrew from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2018. Painstaking negotiations appear to have reached a critical juncture this week, with the U.S. submitting a response to Iran's comments on the text of a final draft agreement. Here's everything you need to know about whether a new agreement will be signed, what is likely to be in it, and what it all means:

Why is a new agreement necessary?

Like nearly all GOP presidential candidates in 2016, Trump promised to tear up the JCPOA, better known as the Iran Deal, on day one. The basic parameters of the 2015 accord were sanctions relief and some degree of economic normalization for Iran in exchange for cooperating with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspections regime, foregoing the pursuit of the highly enriched uranium needed to build a nuclear weapon, surrendering its existing stockpile of highly enriched uranium, and ensuring that existing nuclear facilities were involved in peaceful nuclear activities only. While many Republicans objected to the very idea of negotiating with Iran, others primarily opposed the "sunset provisions" under which certain restrictions expired (mostly at the end of 2030, but some earlier) without a renewal of the agreement.

Although the IAEA repeatedly affirmed that Iran was holding up its end of the bargain, the Trump administration pulled the U.S. out of the agreement in May 2018. Since then, Iran has elected a new hardliner president, Ebrahim Raissi, and inched closer to the point where its so-called "breakout time" — the amount of time needed to produce enough enriched uranium to build a working nuclear weapon — is numbered in weeks rather than months or years. Talks between Iran and the rest of the original parties to the deal, the so-called P5+1, resumed in 2021, but without the United States participating directly, and with the EU taking a lead role. The Trump administration's decision to unilaterally back out of the deal poisoned relations with Tehran so badly that it refuses to negotiate directly with Washington.

What are the sticking points?

The most problematic aspect of putting the Iran Deal back together is trust. When Iran signed the deal in 2015, it led to hopes that the country's economic isolation from the rest of the world would end, and that international companies could do business there. But when Trump reimposed many U.S. sanctions that had been lifted, and successfully discouraged other countries from allowing their firms to operate in Iran, it sent their economy into freefall. From Tehran's perspective, it must have guarantees that the U.S. cannot immediately plunge the Iranian economy into turmoil should a future U.S. president once again decide to scotch the deal. That's why Iran is demanding that it retain the enrichment capacity it has rebuilt since 2018. Reports suggest that Iran seeks to retain under IAEA supervision rather than destroy the supersonic centrifuges needed to resume enrichment, which would accelerate the country's breakout time in the event of a repeat of 2018. The Biden administration has also reportedly agreed to grant international companies a 2.5 year waiver period to continue business operations in the event that sanctions are reimposed.

Also at issue is an IAEA investigation, opened in 2018, into alleged Iranian nuclear activities at undeclared sites. Tehran wanted that probe closed out, but the Biden administration cannot force the IAEA's hand, since it is an independent agency that does not answer directly to Washington. Iranian negotiators also wanted the elite Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps taken off the State Department's Foreign Terrorist Organization list. Tehran has reportedly backed off that demand. Israel, a close ally and client state of the U.S., has been maneuvering to head off a new agreement altogether, or at least to pressure the Biden administration not to soften its negotiating positions to get the deal across the finish line.

Israeli leaders fear that traditional nuclear deterrence would not work on Iran. The Obama administration's decision to forge ahead with an agreement opened a rift between the two countries, and President Biden, whose party is seeking to buck history in November by holding on to one or both chambers of Congress in the midterm elections, can hardly afford an electorally destructive public brouhaha with Jerusalem. However, concerns of a row with Israel must be balanced against the possibility that a deal, and the reemergence of Iranian oil supplies onto the global market, could drop U.S. gas prices further just in time for the elections.

What would a new agreement contain?

All publicly available reports suggest that what has been happening over the past 17 months is tinkering around the edges of the 2015 agreement. In all likelihood, a small number of provisions would be added to the original text of the JCPOA. What is unclear from today's vantage point is whether the original sunset provisions will remain, or whether that timeline will be pushed forward seven or eight years. The U.S. will not lift sanctions related to other Iranian activities in the region, but will unfreeze some Iranian assets. Iran, for its part, is reportedly set to release Western hostages held in the country.

The U.S. sent its response to Iran's comments on the draft text on Wednesday, and if Iran agrees to those terms, an agreement could be reached quickly. If, on the other hand, Iranian negotiators introduce new demands, or refuse to back away from U.S. red lines, the whole thing could collapse with no agreement in place and Iran drawing dangerously close to being able to produce a nuclear weapon. That makes the events of the coming days and weeks are particularly important. If an accord isn't reached soon, talks may not resume until after the U.S. midterm elections — by which time Iran may already have built a nuclear weapon.

You may also like

Jimmy Fallon accused of enabling sexual assault of a teenager

Judge orders FBI to release redacted affidavit behind search of Trump's Mar-a-Lago club