Our New Deal in Steuben County, Part 2: How work programs continue to benefit residents

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As we saw in our previous column, the Great Depression smashed us hard in Steuben County. Corning Glass Works laid off 900 people. Corning City also laid people off, and both employers cut pay for those still left by 10%. St. Mary's Church in Corning saw revenue drop by a third, while enrollment plummeted at St. Ann's School in Hornell. Grace Methodist Church in Corning had to stop its building project for 10 years.

In the northwestern corner of Steuben, potatoes sold for 15 cents a bushel – but cost farmers 30 cents a bushel to grow. Numerous farms were taken for taxes. Mercury Aircraft in Hammondsport was down to one employee.

Bank failures in Savona and Painted Post wiped out people's savings. The school board in Bath “suggested” that teachers “donate” part of their salary back to the district, and provided a sliding scale so that they'd know what was expected. Corning, like most cities, exhausted each year's “relief” budget in a few months. It was a terrifying time.

When Franklin D. Roosevelt became president in 1933, he pledged “a new deal for the American people.” F.D.R. believed in an activist government, and he was determined to get people back to work.

One step that's often overlooked made a lot of difference to us in Steuben. With Roosevelt pushing it, a new constitutional amendment ended Prohibition. Grape growers and winemakers around Keuka Lake were back in business! So were shippers, dealers, basketmakers, bottleblowers, label printers, cork importers, retailers, and a whole host of others.

New Deal construction projects put millions of people back to work. Here where we live, unneeded 19th-century structures were cleared away at Bath V.A., while reforestation planted thousands of trees on the grounds. A new entrance bridge replaced the one that had been declared unsafe years earlier. Before long the center had a new hospital and a new nursing care center, both still in use (along with the bridge).

Another federal project created a new post office (with an interior mural), still in use at Painted Post.

The New Deal also supported local projects. Bath Memorial Hospital got a new wing to connect its two existing structures; Pro-Action has the building now. In addition to the half-dozen schools we saw in our last column, Troupsburg and Hammondsport got new K-12 buildings, while Prattsburgh and Bradford got expansions.

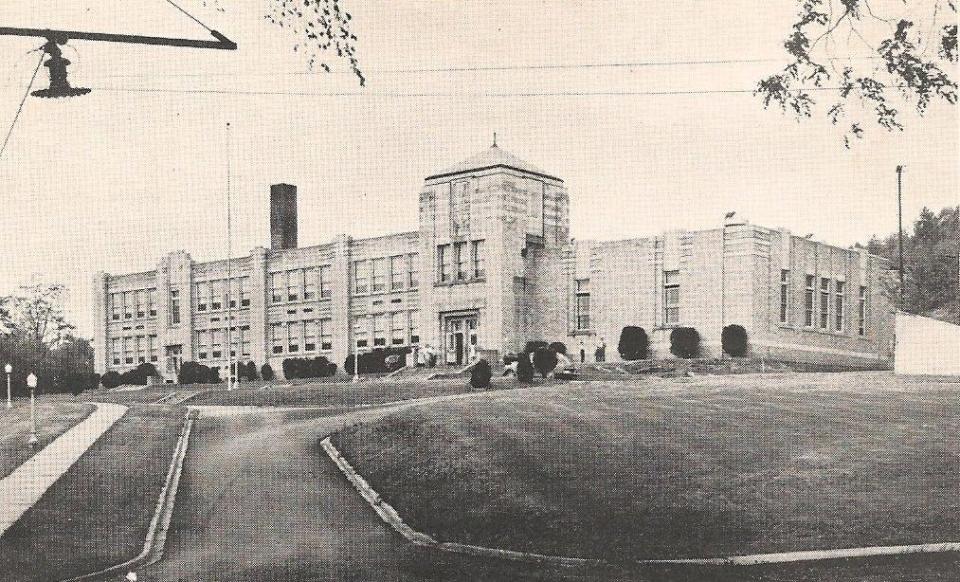

The art-deco Hammondsport school, named for Glenn Curtiss, has interesting sculpted features on its facade, providing work for an artist. The Bradford school has been demolished and replaced, and Curtiss School is now in private hands, but the Prattsburgh and Troupsburg schools are still in action, 90 years later.

The largest New Deal construction project in Corning was the Chemung River Bridge ... or, as we often call it, the Bridge Street Bridge, which still carries thousands of vehicles every day.

After the catastrophic 1935 flood, Cutler Creek in Corning was diked – with New Deal help the city also completed the Wall Street reservoir and pumping system, plus new piping. Addison got flood retaining walls and new storm sewers. In Hammondsport, where the entire village flooded, federal workers helped with the cleanup.

To minimize further inundations, after 1935 local New Deal programs strongly stressed flood control, reforestation, soil conservation, and improved farming techniques. And as we mentioned in the previous column, many people who survived the flood of 1972 did so because of all that work, after the flood of 1935.

Corning, Wayland, and other towns got help with their sidewalks. Farmers suffered badly in the Depression, so a “farm-to-market” program improved roads in Wayne and Prattsburgh.

One fondly-remembered feature of the New Deal was the C.C.C., or Civilian Conservation Corps. Most of these were young men in their teens or twenties, employed for a year on conservation-related work. It gave them jobs, but sent most of their payroll home to their parents. It also provided training with tools and heavy equipment, and got fellows through high-school diploma programs if needed.

More: Stony Brook, schools, roads, dams: How New Deal work programs changed Steuben County

There was a large camp in Kanona, with smaller “side camps” in Painted Post, Addison, and Cohocton. They planted a lot of trees, dug a lot of drainage ditches, helped clean up after floods, and searched for the bodies of those washed away.

In one 12-month period, one New Deal agency alone provided 1.5 million hours of labor for Steuben County residents. It made a world of difference at the time. And it still makes a difference now as students walk the halls at Prattsburgh and Troupsburg; as people mail letters in Painted Post; as veterans head to Bath V.A. for help with their health; as tourists, workers, shoppers, and shippers cross the Chemung River at Bridge Street. It makes a difference when the floodwaters rise.

We can debate whether the New Deal was a wise idea. But in a great many ways, we're still reaping its benefits.

— On Friday, March 1, Kirk House will give an illustrated presentation, “Our Great Depression, Our New Deal.” The free Steuben County Historical Society program takes place at 4 p.m. in Bath fire hall.

This article originally appeared on The Leader: New Deal programs changed face of Steuben County for decades to come