Dean Karau history: Did you know Kewanee is home to the National Corn Huskers Hall of Fame

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

(Author's note: Recently, Larry Lock gave a presentation on corn husking to the Henry County Genealogical Society. Unable to attend, I decided to see what I could learn about the harvesting of one of Kewanee’s most important crops and share it with others who were not able to see Larry’s talk.)

Nine thousand years ago in Mexico, farmers harvested seeds from a wild grass called “teosinte” and began planting them on land from which trees had been cleared. It was the beginning of the domestication of the plant which became “maize.” Soon, maize began to spread throughout Central America and then into both North and South America.

When Europeans arrived in Virginia, Massachusetts, and elsewhere in what became the United States, Native Americans taught them how to grow what we now call corn. As our country grew westward, corn followed.

Techniques for growing and harvesting corn varied by geography, in part dictated by, literally, the lay of the land. But other factors were important, too, such as the use to which the corn would be put.

In Illinois, pork became the primary meat for the pioneers, and corn became the primary feed for hogs. Back East, corn was cut, “shocked” to dry, moved elsewhere to clear the land, and only later “husked.” But in Illinois, corn was husked in the field and then the rest of the plant was left for the hogs to forage and thus clear the land. The intrepid Wethersfield Colonists practiced the latter method. (A method which may have contributed to Kewanee becoming the Hog Capital of the World.)

At harvesting time, Midwest corn farmers would bring in extra help to pick and husk the corn in the fields. Soon, men would develop reputations for how many bushels of corn they could pick and husk for the farmers. And not long after that, America’s penchant for creating competition led to workers pitting their skills against each other in corn husking contests.

According to one expert, “husking bees became common on New England farms in the 18th century, . . . in the South, corn shucking contests were common and local in the 1860s [but] [i]n the 19th century many Midwest farmers created husking matches with small cash prizes to help bring in the crop.”

It was in the 1920s, however, that serious - with a capital “S” - competitive corn husking truly began.

Credit for it becoming a sport falls to Henry A. Wallace, an editor of Wallaces' Farmer magazine. In a 1922 article, Wallace described the details of a corn husking contest in Iowa, and ended with this entreaty to his readers:

“We hope to see the day come when farm people will get as much enjoyment out of watching corn buskers competing for a record as the people of the cities now get out of watching track athletes in their efforts to do unusually well in running and jumping.”

Wallace’s words did not fall on deaf ears, and a true Midwest sport was born. (Wallace later became the Secretary of Agriculture, the 33rd Vice President, and the Secretary of Commerce.)

Wallace subsequently offered a prize of $50 for the husking record for a day, and the first contest took place in Des Moines in 1924. The next year Wallace doubled the prize and set up the rules. Soon, farm magazines became sponsors, donated prize money and crowned husking queens. Churches set up food tents for husking meals. Bands and barbershop quartets, automobile and farm machinery exhibits, educational displays, and other entertainment created a fair-like atmosphere.

Champion corn huskers became national sports heroes, sought by promoters to endorse everything from steak restaurants to insurance policies. But the farm magazines quickly required contestants to sign pledges against paid promotions.

Wallace described husking techniques in the WALLACE’S FARMER magazine and critiqued them:

“Both Rickelman and Paul used thumb hooks. . . . Their method of husking, however, is totally different. Rickelman uses almost invariably the pinch and twist husking method, grasping the ear at the butt with the left hand with the thumb up. The thumb on his right hand brushes the husks aside so that he can grasp the ear and give the twist which usually breaks the ear quite clean of husks. Occasionally, however, the Rickelman method results in a slep-shucked ear. . . . Paul uses the standard hook method, but he has a free and easy, rhythmical swing which makes his husking rather prettier to watch than the Rickelman husking.”

By the 1930s the contests were covered by Newsweek and Life magazines, by radio and newsreel, and one year President Franklin D. Roosevelt even fired the starting gun from the White House. In 1940, the national championship drew a record crowd of between 125,000 and 160,000, second only to the Indianapolis 500 auto race in attendance.

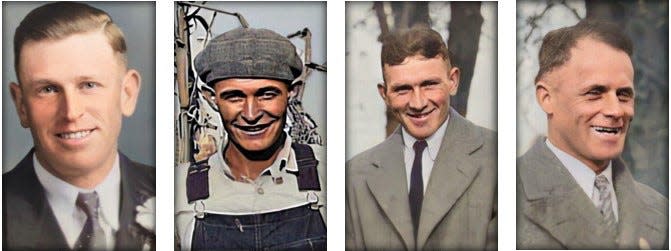

Henry County and Kewanee had its share of competitive corn huskers, and the Robert Peterson farm halfway between Kewanee and Galva was the scene of the 1932 national contest. An estimated 50,000 viewed the event. Carl Seiler of nearby Knox County claimed the championship.

Kewanee’s own Bill Rose was a champion husker. He won the Illinois championship in 1937 and finished 2nd twice (1933 and 1935). As a result, he competed in the national contest three times, with 4th place his best finish.

Others from Henry County reached the national stage. Henry County champion Harold Holmes won the Illinois title in 1929 and 1930 and finished 2nd and 6th at the National. Elmer Williams of Stark County won the 1925 National championship. Walter Olson of Knox County won the 1928 and 1929 National championships.

Another Kewanee connection to cornhusking was the fact that many of the champions used husking hooks made in Kewanee by the Boss Manufacturing Company. The company’s origin in 1880s was based on making the husking devices. During the 1890s Boss began producing cotton gloves also and soon became one of Kewanee’s major industrial concerns.

But World War II abruptly stopped the husking competitions and the combine ended husking by hand. The era of the husker as a sports icon was over.

The Kewanee Historical Society’s museum is the home of the National Corn Huskers Hall of Fame. Stop in sometime to learn more about this truly original, Midwest sport.

And consider inviting Larry Lock to give his presentation to your organization. You’ll learn so much more, and your group won’t be sorry.

This article originally appeared on Star Courier: Did you know Kewanee is home to the National Corn Huskers Hall of Fame?