Death of Caesar Montevecchio, 89, marks end of Erie's 'gangster' era, but a probe lingers

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In the early 1980s, Erie was plunged into a vortex of organized crime.

A series of house burglaries netted a ring of thieves hundreds of thousands of dollars in stolen jewelry, watches and other valuables.

Some Erie police officers were under suspicion in one of those burglaries — an estimated $550,000 in jewelry, coins, gold and silver and other items taken from the home of Louis Nardo, on Hilltop Drive in the affluent Glenwood Hills neighborhood on Nov. 25, 1980.

About a month later, Erie police Cpl. Robert Owen was shot to death. He was found near his patrol car in a desolate parking lot of a warehouse at West 18th and Cranberry streets on Dec. 29. 1980. Owen was killed with his own service revolver.

And on Jan. 3, 1983, Erie bookmaker Frank "Bolo" Dovishaw, 46, was killed execution-style in the basement of his home in the 1600 block of West 21st Street. He died from a single gunshot wound to the head. His feet and hands were bound and a rug covered him.

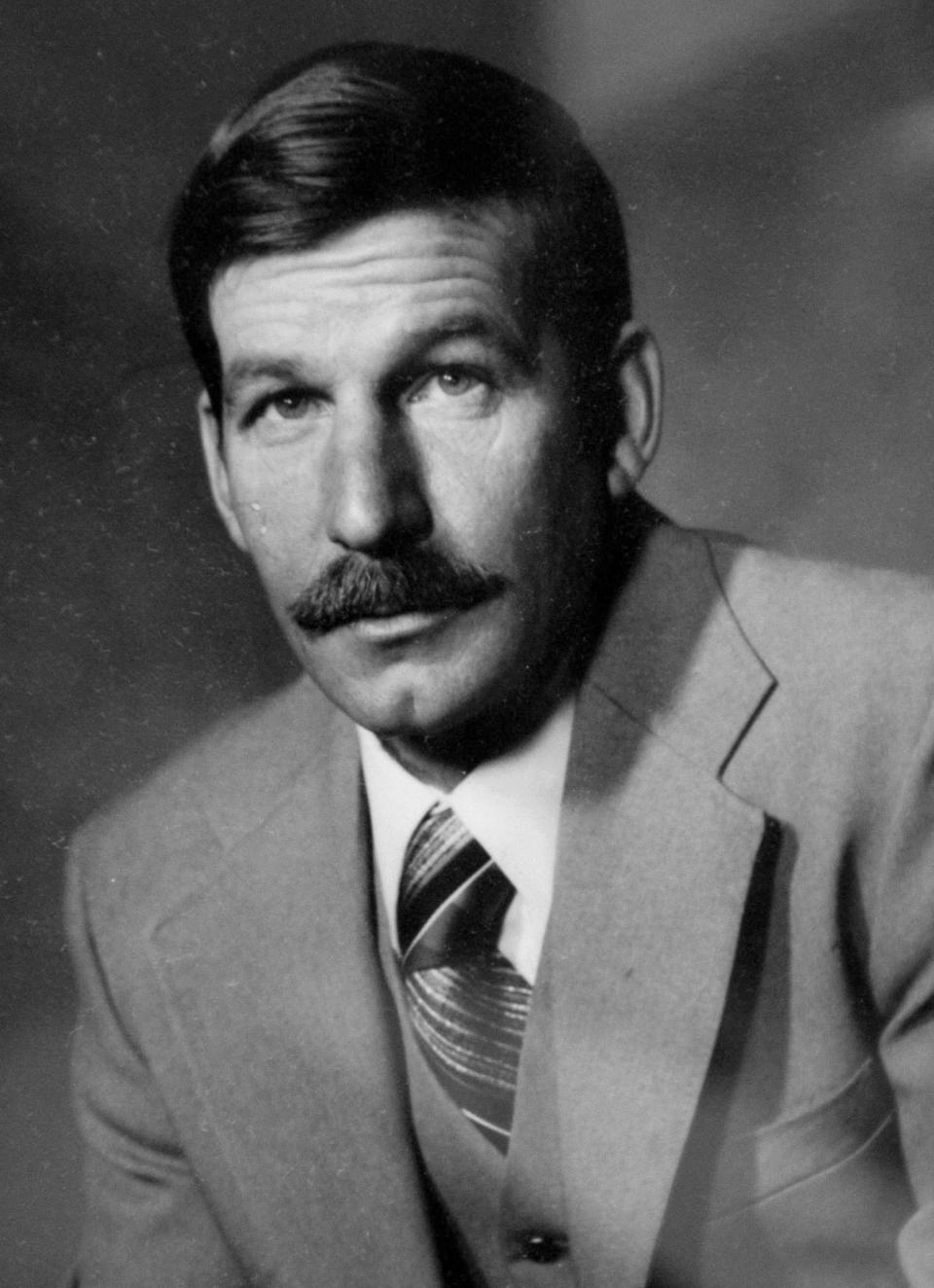

At the center of much of the mayhem was Caesar D. Montevecchio, who died on Aug. 10.

The Erie crime figure pleaded guilty in the burglaries and to hiring a hit man from the Cleveland area, Robert Dorler Sr., to kill Dovishaw.

Montevecchio's name also came up constantly in the investigation of Owen's death, which remains Erie's most notable unsolved homicide.

"He was an interesting guy," recalled Leonard Ambrose, one of Montevecchio's many criminal defense lawyers. "He was colorful. He was involved in a lot of different things."

Montevecchio's death, at 89, all but closed out a period when a web of underworld criminals shocked the city of Erie with their ruthless bravado.

For a time, Erie, with its central location between New York and Ohio, turned into a violent playground for mobsters connected to nearby cities, such as Cleveland, Buffalo, Pittsburgh and Youngstown.

"That was an era where there was a lot of gangster-related activity," said Ambrose, 75.

Just as crime in Erie changed, Montevecchio changed later in life.

He stayed out of trouble after he was released from prison in 1995, when he was 61. The married father of eight spent much of his time gardening, watching sports on television and helping to care for his 14 grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

"God worked in mysterious ways in Caesar's life," the Rev. Michael Ferrick said in his homily during Montevecchio's funeral Mass Aug. 14 at St. Peter Cathedral.

Caesar Montevecchio, star athlete, was 'Prep's little giant'

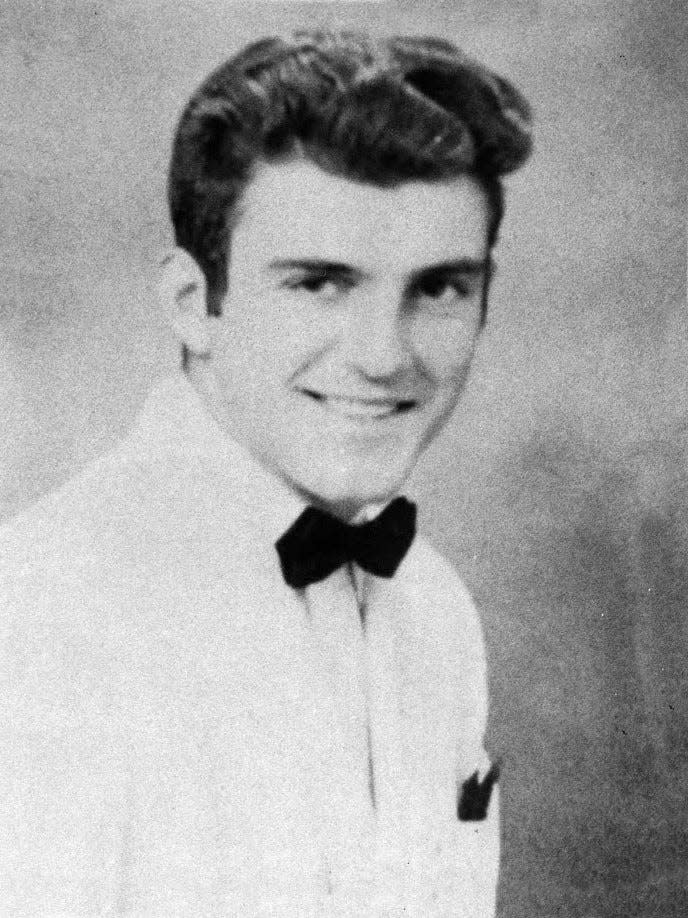

Why Montevecchio engaged in a life of crime for so many years remains something of a mystery. He seemed to be poised for success when he graduated from Cathedral Preparatory School in 1952.

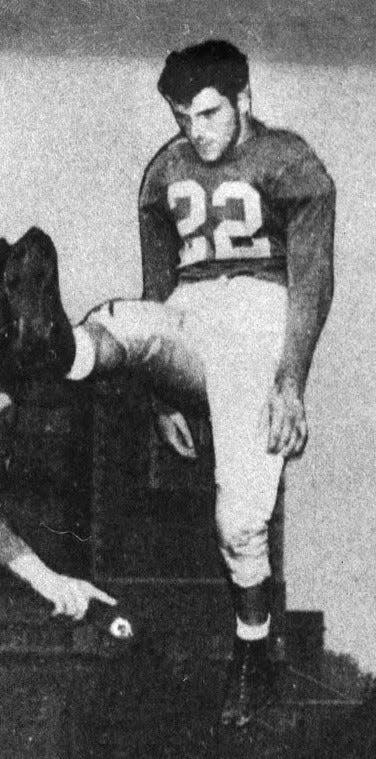

Montevecchio, who attended parochial grade school, played basketball and baseball at Prep and was the quarterback and kicker for its football team. In Montevecchio's sophomore year, in 1949, the Ramblers won their first City Series football championship. The team won the title again in 1950 and 1951, with a 9-0 record. Montevecchio led the way.

"He was a big man back then," said Erie County Judge Daniel Brabender, 70, who attended Montevecchio's funeral and got to know Montevecchio as Brabender researched the books he wrote on high school sports in Erie, including "Ramblers: The History of Cathedral Prep Football," published in 2000.

"He was a fine athlete, no doubt about it," Brabender said.

Montevecchio was also known for his good looks and his quiet but self-confident manner. "Chaz," as he was called at Prep, was described as "Prep's little giant" in the school's 1952 senior yearbook.

"A calm and cool manner is the secret of his success," according to the yearbook entry. "His five-o'clock shadow and quaint comment will be sorely missed. Caesar's love for sports will be turned into a career, as he plans to play professional baseball."

Montevecchio won a football scholarship to the University of Detroit but ended up returning to Erie. He enlisted in the Army in 1955. He later worked for Marx Toys and the Fenestra Corp. in Erie, according to an article in the Erie Morning News in August 1983.

Montevecchio had a criminal record as a juvenile for larceny and receiving stolen property, but became enmeshed in much more serious crimes as an adult. At 33, he was charged in 1967 in a federal probe of gambling, attempted homicide and other crimes in Ohio, Pennsylvania and Michigan.

Montevecchio was charged with bank robbery in Boston in 1968, and charged that same year with armed robbery of $11,655 from the John Hancock Insurance Agency and the robbery of $470 from an Eckerd drug store, both in Erie. He ended up going to prison for about 10 years and was released in 1978, two years before the burglary spree in Erie.

According to court records, Montevecchio was working at the now-closed Hammermill Paper Co. in Erie when he was charged in the break-ins in 1983.

"He was a smart guy," said another of Montevecchio's lawyers, retired Erie attorney Frank Kroto, 85. "It's a shame the path he took. As I knew him, and in my dealings with him, he was a nice guy and a gentleman."

Montevecchio outlasted many of his associates, pursuers

At 89, Montevecchio outlived many of his friends and associates.

Anthony "Nigsy" Arnone, who was acquitted in 1989 of charges that he recruited Montevecchio to hire Robert Dorler, the hit man in the Dovishaw case, died at 71 in Erie in 2010.

Dorler died in prison in 2008. He was 72.

Raymond W. Ferritto, another hit man for the mob who testified with Montevecchio at Arnone's trial, died at 75 in Sarasota, Florida, in 2004.

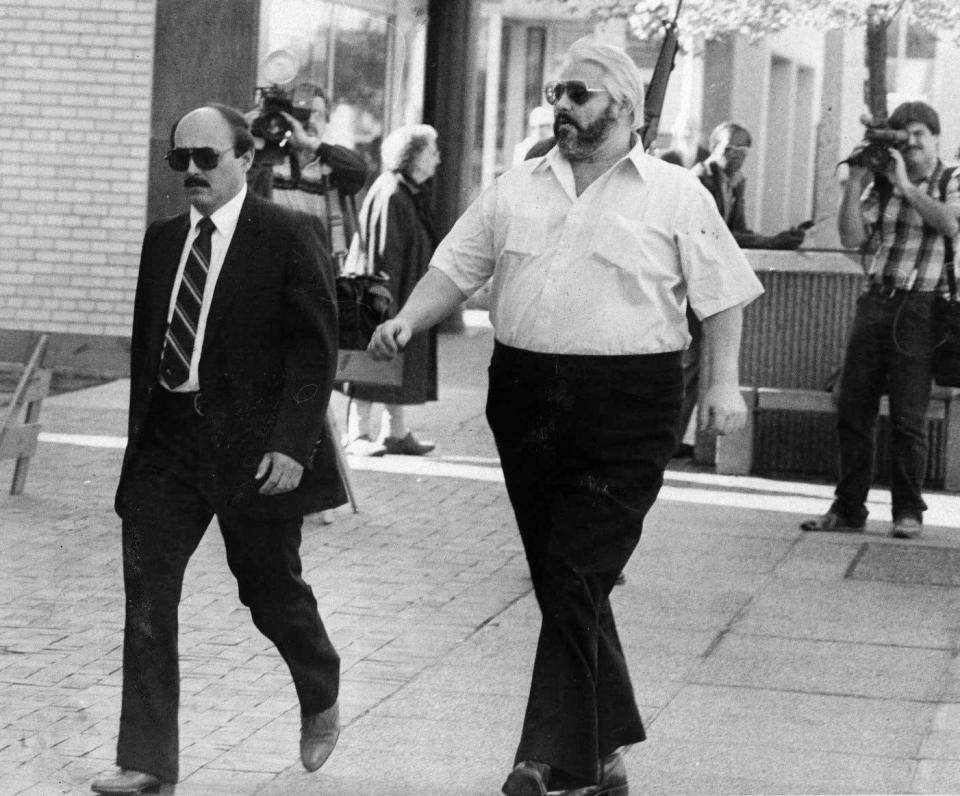

Another Montevecchio associate, Sam "Fat Sam" Esper, who secretly recorded Montevecchio in the Dovishaw case, may or may not be still alive. He entered the federal witness protection program in 1984, when he was 39. He would be 78 today.

Esper's recordings, made in July 1983, led to the filing of charges in August 1983 against Montevecchio and others in the Nardo burglary and the filing of charges in 1987 against Montevecchio and others in Dovishaw's slaying — developments that spurred the probe into the death of Owen.

Others who knew Montevecchio from the other side of the justice system included Michael Veshecco, the Erie County district attorney from 1979 to 1987. He died at 66 in Erie in 2014.

Barry Rice, who helped investigate the Dovishaw case as an agent with the Pennsylvania Attorney General's Office, died at 57 in Meadville in 2006. The Attorney General's Office prosecuted the Dovishaw cases.

The lead investigator in the case was Dominick DiPaolo, 76, who at the time was an Erie police detective sergeant. He retired in 2018 as the district judge for Erie's 6th Ward and in 2014 co-wrote a book about the Dovishaw case, "The Unholy Murder of Ash Wednesday." He said Montevecchio put out a contract on his life in 1984.

"Naturally I dealt with him for a long time with the Dovishaw case," DiPaolo told the Erie Times-News when asked about Montevecchio's death. "Even though he wanted to kill me, he did his time and I'm not going to comment."

What did Montevecchio know about the slaying of Cpl. Owen?

In a previous interview, DiPaolo was adamant that Montevecchio was not connected to Owen's killing.

Owen, 40, was found dead shortly after 1:40 a.m. on Dec. 29, 1980, according to police. Later that day, authorities said, he was scheduled to take a lie-detector test about a theft of a $1,000 diamond ring during the probe of the Nardo heist.

The possibility that Montevecchio might have been involved in Owen's death surfaced partly as the result of a conversation that Esper had with Montevecchio when Esper was wearing a wire in July 1983.

"You know who killed Owens," Montevecchio said to Esper.

"No, I don't," Esper said.

"Sure, you do," Montevecchio said.

A year later, in 1984, a federal grand jury in Erie heard evidence in the Owen case. No one was indicted.

In a 2011 interview with the Erie Times-News on the Owen case, DiPaolo said he brought up the killing with Montevecchio during the Dovishaw investigation.

"He had no knowledge of it, and his cronies didn't," DiPaolo said. "They had no part of it. All Montevecchio knew was what he picked up on the street."

Also in 2011, the Erie Times-News asked Montevecchio about Owen's death.

Montevecchio, interviewed at his home on Harvard Road in Erie, said he had "no idea" who killed Owen, whom he said he never met. He said Owen's death had nothing to do with the burglary operations or organized crime.

"I think it was totally unrelated, or I think I would have known about it," Montevecchio said. "So I know it is not related."

"I hope they solve it," he said.

What is status of the Owen probe?

The state said the Erie police's initial handling of the Owen case hindered the investigation.

The police messed up the probe, according to an evaluation in April 1983 from the state attorney general at the time, LeRoy S. Zimmerman.

He got involved at the request of then-Erie County District Attorney Veshecco, who asked for an independent review because of the Erie police's rift over whether Owen was the victim of a suicide or a homicide.

Zimmerman's office assailed the police in a 93-page report never made public. In summarizing his findings in April 1983, Zimmerman faulted the police for initially concluding Owen killed himself. He agreed with Veshecco and then-Erie County Coroner Merle Wood, who in early 1981 ruled Owen's death a homicide.

"Homicide is the only plausible explanation," Zimmerman said.

"We found that the investigating officers committed numerous errors," Zimmerman also said, "errors in judgment, errors in evidence collection, errors in documentation and errors in analysis."

The state police took over the Owen case. The probe remains active.

"It is still an open investigation," said Lt. Mark Weindorf, crime section supervisor for state police Troop E in Lawrence Park.

'You killed somebody and got paid in salami and capicola?'

Montevecchio was the star witness at two sensational trials.

One was for Dorler, the hit man who was convicted in November 1989 of first-degree murder in the death of Bolo Dovishaw. The other was for Arnone, who was acquitted in December 1989 of arranging Dovishaw's murder by paying Montevecchio to hire Dorler.

At Arnone's trial, Montevecchio, then 55, testified that Arnone came up with the plot to kill Dovishaw. The intent, according to testimony, was to steal keys to safe-deposit boxes in which Dovishaw was thought to keep as much as $300,000 in cash from his Erie gambling operation, which included taking bets on professional football games.

Montevecchio said Arnone agreed to pay him $10,000 to arrange the hit, but Montevecchio said he agreed to have Arnone owe him $9,000 and partially pay him in free groceries. Arnone was president of the now-defunct Arnone & Sons Food Importers, at West 18th and Cherry streets, in Erie's Little Italy.

Montevecchio's comment led Arnone's lawyer, Joseph Santaguida, to question Montevecchio on cross-examination.

"You killed somebody and got paid in salami and capicola, is that what you're telling us?" Santaguida said with a raised voice.

"That is partially true, yes," Montevecchio said.

"Getting paid off for a murder with $50 worth of groceries?" Santaguida said.

"That's correct," Montevecchio said.

Santaguida, of Philadelphia, died from the coronavirus in May 2020. He was 81.

Dorler, the hit man, was sentenced to life in the Pennsylvania state prison system in February 1990, when he was 54.

At his sentencing in the Dovishaw case, Dorler proclaimed his innocence. He criticized the plea bargain that Montevecchio got in exchange for his testimony.

"Nice deal," Dorler said.

Montevecchio in 1987 pleaded guilty to third-degree murder in Dovishaw's death and he pleaded guilty to three high-profile burglaries, including the Nardo heist. After testifying against Dorler in 1989, Montevecchio in February 1990 was sentenced to 7½ to 15 years in prison on all the charges to which he pleaded guilty.

Also as part of the plea deal, the sentence was made concurrent to a 15-year federal sentence. Montevecchio got that sentence after he pleaded guilty in 1986 in U.S. District Court in Erie to possession of cocaine with intent to deliver. He was at a federal prison in Indiana when he was charged in the Dovishaw case.

Montevecchio's sentence of 7½ to 15 years in the Dovishaw case was made retroactive to when he started the federal sentence, in 1987.

The arrangement allowed Montevecchio to get released in 1995, after he served the minimum sentence.

The end of a crime-ridden period for Erie

By the mid-1990s, organized crime had faded in Erie, and the violence was due more to drugs. But for nearly a decade before then, Montevecchio and his associates had established criminal enterprises throughout the city, including illegal gambling, with many of the same people coming up again and again in investigations.

"It was operating as a continuous course of conduct," said Erie lawyer Paul Susko, 71, an assistant Erie County district attorney from 1983 to 1987. "It was sort of a revolving door."

Ambrose, one of Montevecchio's lawyers, summarized law enforcement's extraordinary interest of Montevecchio in a court motion that Ambrose filed in 1984, in the burglary cases. He filed the motion a year after Dovishaw was killed, but five years before the case went to trial.

"The case of the Commonwealth versus Caesar Montevecchio has been the focus of a great deal of attention of the law enforcement community in the Erie County area," Ambrose aid in the motion, filed Dec. 13, 1984, in Erie County Common Pleas Court. "It is marked by investigations by the Pennsylvania State Police, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Pennsylvania Attorney General's Office and the Erie Police Department.

"Mr. Montevecchio has also been the focus of an inquiry by a Federal Grand Jury seated in Erie. At times, Mr. Montevecchio has been suspected of crimes ranging from conspiracy to killing-for-hire to the murder of a police officer."

Later in life, Montevecchio found solace in penance

At Montevecchio's funeral, the focus was different. It was on his generosity and his love for his family and his dedication to his Catholic faith.

No one mentioned Montevechio's past during the service.

Ferrick, the rector of St. Peter Cathedral, said Montevecchio was most proud of his return to the sacrament of reconciliation. Without providing details, Ferrick said Montevecchio was glad he embraced confession as he became faithful once more later in life.

Ferrick in his homily recounted a conversation he had with Montevecchio.

Montevecchio, he said, told him that going to confession was "the best thing he did."

Cold cases: Partnership between DA, investigators pushes to resolve unsolved major crimes in Erie area

Staff writer Tim Hahn contributed to this report.

Contact Ed Palattella at epalattella@timesnews.com. Follow him on X @ETNpalattella.

This article originally appeared on Erie Times-News: 'Gangster' era in '80s Erie ends with death of Caesar Montevecchio, 89