Death of Grosse Pointe Woods man haunted Oprah Winfrey, inspired documentary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

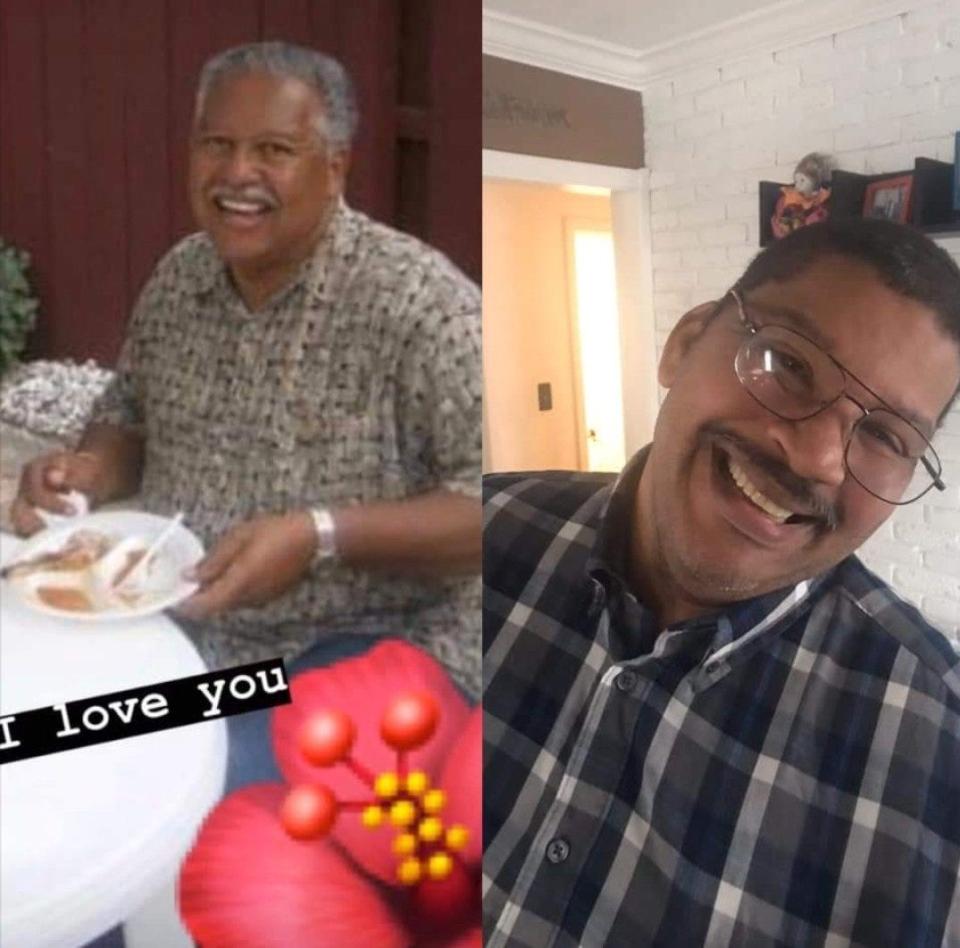

Keith Gambrell wears a pair of gold teddy bear pendants around his neck that contain the ashes of his father and grandfather, lost early in the pandemic to the coronavirus.

Gambrell took his dad, Gary Fowler, to hospital after hospital over the course of several days in the spring of 2020 as his breathing grew more and more labored.

Fowler was never given a coronavirus test — even though he couldn't breathe and even though he'd been in close contact with his father, David Fowler, who had tested positive, and was hospitalized.

Gary Fowler ended up back at his house in Grosse Pointe Woods, where he died April 7, 2020 while sitting in his favorite blue recliner beside the love of his life.

More: Family ravaged by coronavirus begged for tests, hospital care, but was repeatedly denied

More: Opinion: Health equity in Michigan: Making progress, but still miles to go

Scrawled on a piece of paper beside him was a note that said: "Heart beat irregular ... oxygen level low." He was 56 years old.

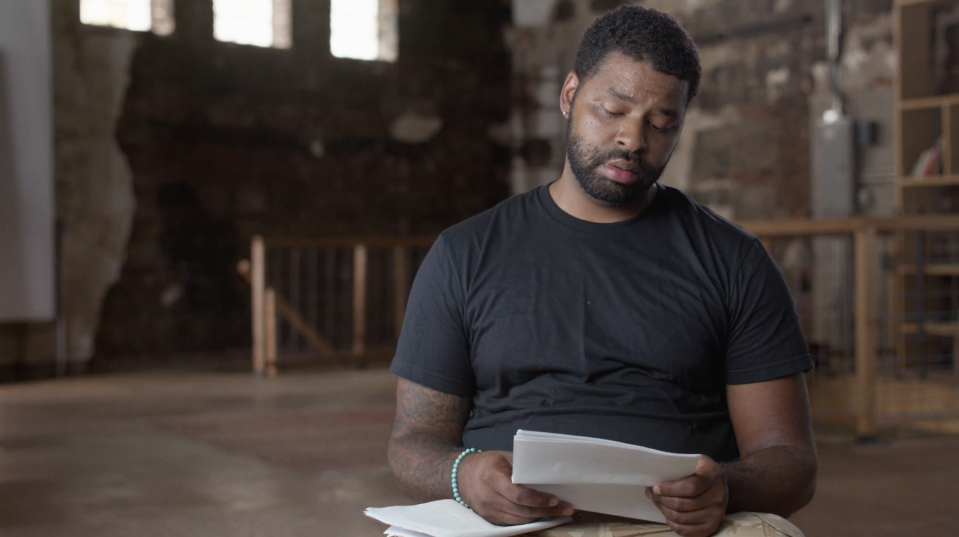

Gambrell first told the Detroit Free Press the story of his family's struggle to get medical care. The account also was published in USA Today, and that is where Oprah Winfrey saw it and was stirred to action.

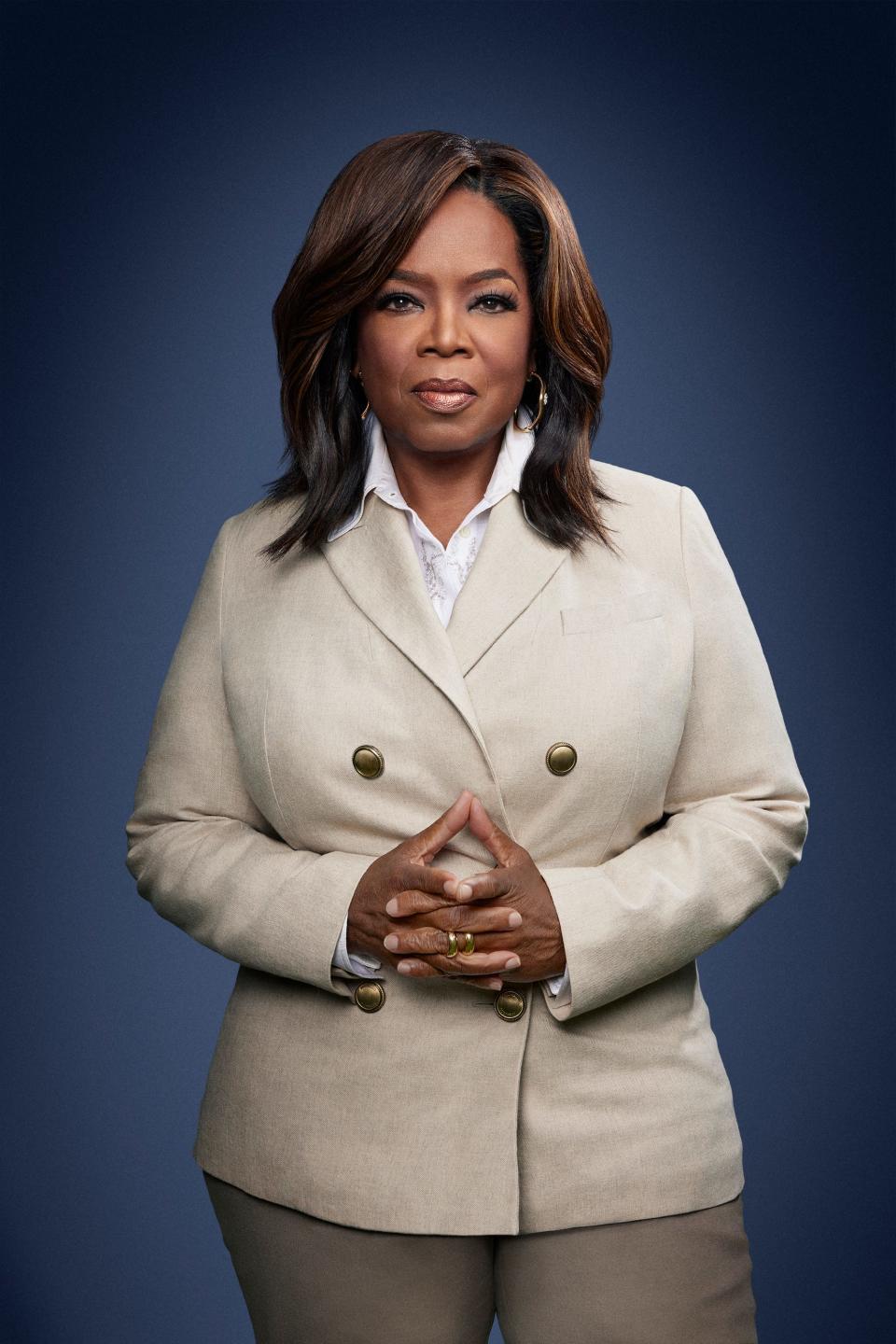

"I was haunted by the words of the story and that picture," Winfrey said of Gambrell, who was photographed staring through the window of his northwest Detroit home. "In the middle of the night, I woke up thinking about that."

More: Report: Michigan improves COVID-19 racial disparities, but more work is needed

More: America forgot about my dad's death. Don't let that happen to Floyd, Arbery and Taylor.

The story, she said, humanized and laid bare the racial disparities playing out in a pandemic that has continued to ravage Black and brown communities, disproportionately sickening people of color and taking their lives.

"It was so vivid in my mind that I thought, 'Oh, this would make its own movie. This would make its own film if you could tell the story,' " Winfrey told the Free Press.

[ Not a digital subscriber to the Free Press? Your contribution makes work like this possible. Subscribe here today for just $1 for 6 months of exclusive access. ]

In the months that followed, Winfrey met with her Harpo Productions team and partnered with the Smithsonian Channel to make a documentary, "The Color of Care." It highlights the Fowler family and about a dozen others who endured their own painful pandemic losses.

For Winfrey, the goal was not only to make a documentary, but to bring about change.

"It's a moment to ignite a cultural conversation around this public health crisis, and ... to move the conversation forward because there's so many people who aren't even aware that this is what is happening," Winfrey said.

"I want people to be aware that because of the color of your skin, there are disparities in your ability to receive your rightful health care. What we're trying to do is have this campaign ... it's a yearlong campaign … reach current and future medical professionals."

More: Michigan family devastated by coronavirus takes another hit

More: Report: Lenders still approve whites at higher rate than Black applicants in Detroit

Black Americans are more likely to have diabetes, obesity and high blood pressure than white Americans, all of which are risk factors for severe coronavirus illness and death.

The COVID-19 death rate is higher for Black Americans, too.

The film showed that as of Jan. 8, the mortality rate among Black Americans was 4.25 per 100,000 people — about twice the rate it was for Asian/Pacific Islanders, at 2.17 per 100,000. For white Americans, the mortality rate was 3.87 per 100,000.

Although Dr. Hetty Cunningham knew racial health disparities were likely to surface in the COVID-19 pandemic, she didn't expect to see the level of devastation COVID-19 brought in communities of color in the U.S.

"The degree and the magnitude of the COVID health disparities took me by surprise," said Cunningham, an associate professor of pediatrics at Columbia University Irving Medical Center and director of equity and justice in curricular affairs at Columbia University's Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

"I first started hearing about it from my family and friends who live here in New York.

"They were telling of the similar types of stories that are featured in this film of going to the emergency room, being turned away, calling for help, having even the EMTs come and say they weren't sick enough to go to the hospital and then them passing away.

More: Whitmer mandates implicit bias training for Michigan health care workers

"So I was starting to hear this before the disparities kind of hit the news. ... When they did hit the news, then I was shocked along with everybody else — even with the background that I have in health disparities."

She never got training in implicit bias or racial health disparities when she went to medical school three decades ago.

"We're doing that now," she said.

The Smithsonian Channel and Harpo Productions are collaborating to screen "The Color of Care" to the full membership of the Association of American Medical Colleges.

The public can watch it at 8 p.m. Sunday on the Smithsonian Channel. It also will premiere simultaneously for free on Smithsonian Channel Selects on Pluto TV in the U.S. as well as on the Smithsonian Channel Facebook and YouTube sites. The film will be available to stream for free until May 31.

"What excited me about working with Smithsonian is that they want to get this film into the medical schools, and so that's where you're actually going to make the change, where people get to see and hear themselves from the doctors and from ... all of the people who participated in this film," Winfrey said.

"And so what's going to happen is now multiple other people will see that film who are also in the medical community and say, 'Now, what can I do?'

"And so that's how we have change, how we bring about change. It all started with that ... one story of yours."

The film's director, Yance Ford, said he and producer Kate Bolger worked with a crew who fanned out across the country looking for other families like Gary Fowler's.

They found Detroiter Desha Johnson Hargrove, whose husband, Jason Hargrove, drove a Detroit Department of Transportation bus when he got COVID-19.

She tells the story in the film about how Jason Hargrove went to DMC Sinai-Grace Hospital and was sent home twice. On his third visit, he was admitted and within a few hours, needed a ventilator.

He died on March 31, 2020, but no one called to tell her.

"I never received any information from the hospital," Johnson Hargrove said. "If it hadn't been for me calling them, I never would have known anything.

"My husband had died. He has passed away and I never got a phone call. ... My husband lay dead all of those hours, all of those hours, a whole day, before my call to the hospital to even find out that he had passed."

The Detroit Medical Center, which operates Sinai-Grace, issued a statement, which read in part:

"Although we cannot disclose the treatment of any particular patient, many patients in the vulnerable population that we specialize in caring for at the DMC arrive at our hospital with a very severe form of COVID illness. Despite our best efforts, some patients may ultimately succumb to COVID.

"COVID is a terrible disease, even for people with low risks. At Sinai-Grace Hospital, we took all steps available to assist this patient, as we do with all our patients. To imply or state that we did not, especially due to racial inequities, is not correct. The DMC and Sinai-Grace pride ourselves as a leader in addressing this issue as demonstrated by our unwavering commitment to treating every patient with the best care available and ensuring dignity and respect remain part of our care."

Ford said Detroit became a character in the film because of the Hargroves and the Fowlers, but also because of the concentration of the Black community in Detroit.

It's the biggest majority Black city in America.

More: Michigan facing shortage of primary care physicians, to get worse by 2030

More: Students of color, ninth graders, more likely to be held back in school in Michigan

"Detroit has a lot of essential workers who are African American, who couldn't do their jobs from home and don't really, like most of us, have the ability to say, 'Well, I guess I'm just not going to get a paycheck.'

"But the families in Detroit, they're so resilient. They're fully aware of the system in which they are caught, right? That's the thing about the families in the film and the families in Detroit.

"They know that they're caught in it, but the thing is that they don't know how to get out. That's one of the biggest takeaways from this is that everyone is aware they might not be getting the best care, but they don't know how to change the dynamic."

The Fowlers, the Hargroves and others who tell their stories in the film didn't want their loved ones' deaths to be in vain, Ford said.

"There was a lesson to be learned from what had happened," he said.

"For as difficult as it is for us to listen to these stories, when we were shooting them and when we were in the edit, we never lost sight of the ultimate goal, which is to turn them into teachable moments for other people. ... For us, we knew that on the other side of all of that pain were going to be stories that resonated throughout the nation."

Gambrell said he hopes his father's story does just that.

"I just want to see this whole thing through," he said. "I just want to do everything for my dad and keep his name alive. I want to make sure no one else has to go through what we went through as a family ever. So if this film changes one person's point of view of helping someone when they come to the hospital for medical procedure, I think we did our job very well."

Even two years after his father's death, the pain lingers.

"It doesn't get easier," he said. "You just learn how to live with it, you know?"

Contact Kristen Jordan Shamus: kshamus@freepress.com. Follow her on Twitter @kristenshamus.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Oprah Winfrey's 'The Color of Care' documentary features Michigan man