The death penalty is not a deterrent | Editorial

Fourth in a series

There are some assumptions people hold in absolute — but unfounded — faith that they must be true. One is that the death penalty deters murder. That’s like the faith of some primitive societies that human sacrifices would placate their gods.

As it has fallen in popularity and practice, execution has come to be a random symbolic ritual with no logical nexus between who dies and who doesn’t. Florida courts try more than 1,000 homicide cases annually, but there were only seven death sentences in 2020, down from 47 in 1991. Meanwhile, 797 people were sentenced to Florida prisons for homicide. So the risk to a killer of going to death row is about 1 in 100.

But so long as it is an option, some prosecutors will continue to seek it, at great cost to the taxpayers and at great risk of executing someone who is innocent.

Inconveniently for true believers, the murder rate in New York, which has repealed the death penalty, is barely half as high as in Florida, which hasn’t. Annual murder rates are consistently higher overall in the death penalty states than in the 22 without capital punishment.

According to a landmark investigation by the Sacramento Bee, murder rates over 15 years tracked almost the same — mostly down — in New York, which had no executions; California, which had 13; and Texas, the nation’s leader, with 447.

In a nationwide survey of criminologists in 2009, 94 percent said there was little empirical evidence supporting the deterrent theory, 88 percent didn’t consider it an effective deterrent, 91 percent said politicians use it to appear tough on crime, and 75 percent said it distracts legislatures from real solutions.

But some politicians cling to the debunked theory, even analogizing execution to a celebration of life. Former Florida Gov. Bob Graham, for one, said of his first death warrants, “There will be less brutality in our society if it is made clear we value human life.” More recently, proponents have cited “catharsis” and “closure” as justifications for the death penalty.

“Catharsis” is a euphemism for bloodlust, a motive society repudiated when executions stopped being public spectacles and were hidden inside prison walls, not to be photographed, filmed or even seen except by handfuls of official witnesses and survivor families.

“Closure” implies that relatives of murder victims want the relief that executions supposedly provide. Some do, but others don’t, preferring the prompt satisfaction of a life sentence without parole to the prolonged series of appeals that modern standards of due process demand.

It used to take an average of 14.9 years from sentence to execution in Florida, but the last 10 have averaged 23 years with the longest case taking 33 1/2.

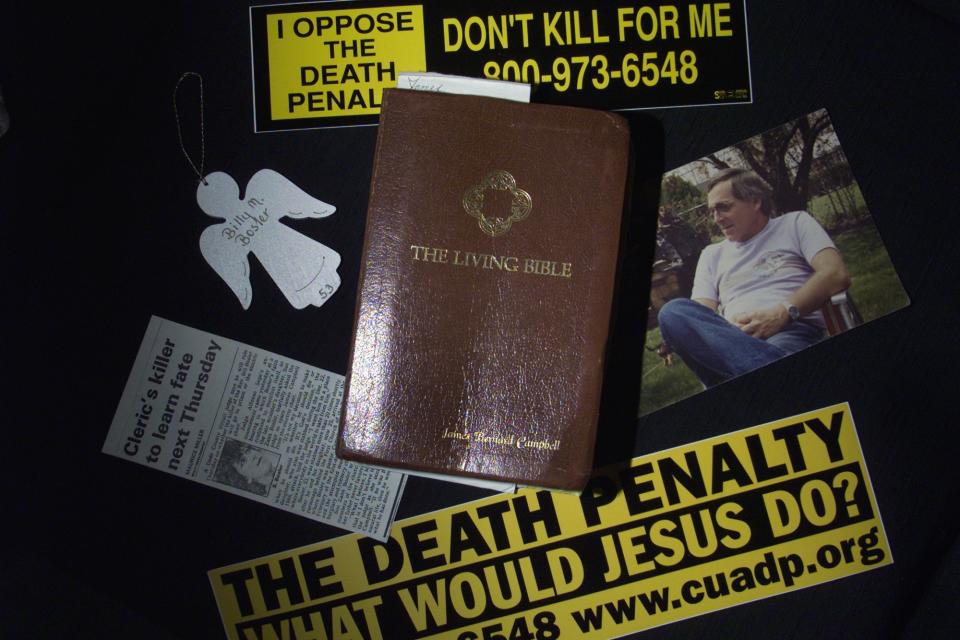

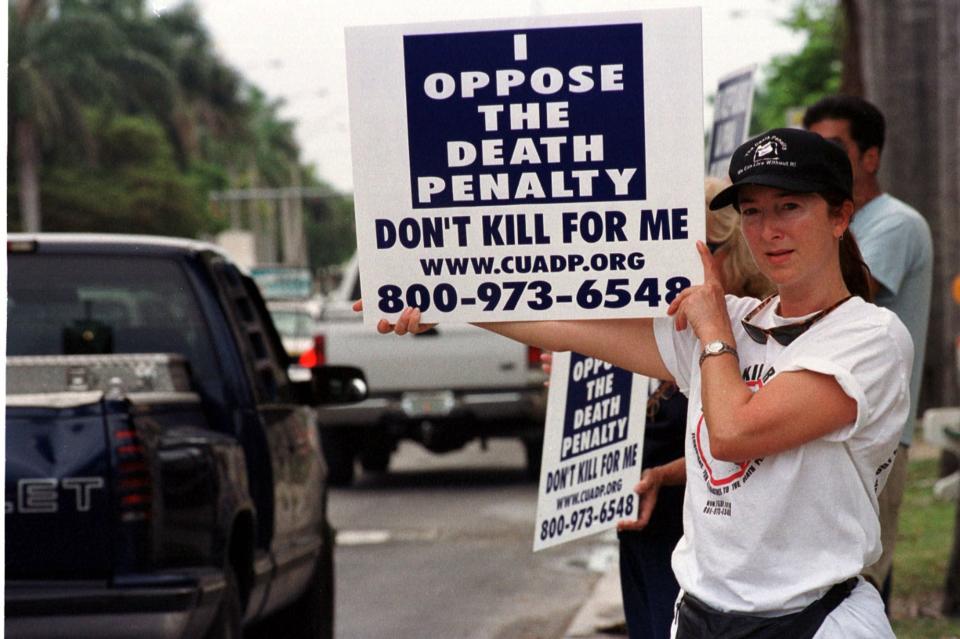

Some victim survivors oppose the death penalty for moral, personal or religious reasons. Among them is SueZann Bosler of Hollywood, an active member of Floridians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty.

Seriously wounded in an intruder’s relentless knife attack that killed her father, the Rev. Billy Bosler, of Opa Locka, she successfully advocated a life sentence for killer James Campbell — as she said her father would have wanted — but it was a drawn-out and painful process involving two trials and repeated court appearances.

“His title is a murderer, and if I were to help the government give him the death sentence, what would you make me? I said to myself that would make me a murderer, too,” Bosler said in an interview with the Sun Sentinel editorial board.

“First of all, I don’t want ‘closure’ in my vocabulary,” she said, describing the emotional ordeal of facing the killer and reliving the crime over and over, only to have a prosecutor treat her like an “enemy of the state” — her words — when she opposed his efforts to get the death penalty.

“I’m still going through things because of those 10 1/4 u00bd years they put me and my family through,” she said. “The courts have got to stop giving us more trauma to go through.”

A 2012 Marquette Law Review study compared survivor family members in Texas and Minnesota, a non-death penalty state. Those in Minnesota were better emotionally and psychologically because “the appeals process was successful, predictable and completed within two years after conviction.” In Texas, it was “drawn out, elusive, delayed and unpredictable.”

If the death penalty isn’t a deterrent and its other values are so tenuous, why keep it? What might persuade the Legislature to repeal it?

“I would look at the cost,” says Harry Shorestein, a former state attorney in the circuit serving Duval, Clay and Nassau counties. “It doesn’t serve any purpose. It just doesn’t.”

Originally a supporter of capital punishment, Shorestein began encouraging his assistants to take it off the table in exchange for guilty pleas.

“You know how long it takes for a guilty plea? Fifteen minutes. You know how long it takes for a death sentence? Thirteen years,” he told them.

The death penalty is most effective as a tool for law enforcement officers and prosecutors to extract confessions and testimony against co-defendants. Nonetheless, those in states without the death penalty have other inducements available.

As a public defender in New York explained to us, prosecutors can still bargain over degrees of homicide, sentence lengths, parole eligibility and whether sentences for multiple crimes would run concurrently or one after the other.

“There’s definitely a tremendous amount of leverage built into the statutes and sentencing guidelines,” he said.

In Florida, prosecutorial decisions of what charge to file and whether to seek the death penalty reflect wide discretion. According to the Office of the State Courts Administrator, Florida’s 20 state attorneys filed about 16 percent of their homicide charges as capital cases in fiscal 2019-20, but the rates varied from 31.9 percent in the Panhandle First Circuit to zero in three others, including the Fourth (Jacksonville) where Republican primary voters in 2016 turned out a death-seeking state attorney in favor of a reform candidate.

Consistency is elusive. Florida executed Leo Jones in 1998 for murdering a Jacksonville policeman despite compelling evidence of another man’s guilt. Dan Hauser died in 2000 for strangling an exotic dancer after he refused to appeal and volunteered, in effect, to be executed. But prosecutors in Pinellas waived the death penalty for John Jonchuck, who had dropped his five-year-old daughter from a bridge in full view of a state trooper. Christopher Vasata, known as the Super Bowl killer, is serving life for three murders for lack of a unanimous death recommendation from the Palm Beach jury that convicted him. A Broward jury spared three men convicted of murdering a sheriff’s deputy. And in Palm Beach County, Clem Beauchamp got life sentences in exchange for pleading guilty to the murders of his ex-girlfriend and her two children.

There were plausible reasons for each outcome, but the bottom line is that the death penalty in Florida is capricious, unpredictable and unrelated to public safety. It should be repealed.

Editorials are the opinion of the Sun Sentinel Editorial Board and written by one of its members or a designee. The Editorial Board consists of Editorial Page Editor Rosemary O’Hara, Dan Sweeney, Steve Bousquet and Editor-in-Chief Julie Anderson.