As The Deaths Pile Up, Experts Ask: Why Are Police Involved In Mental Health Crises?

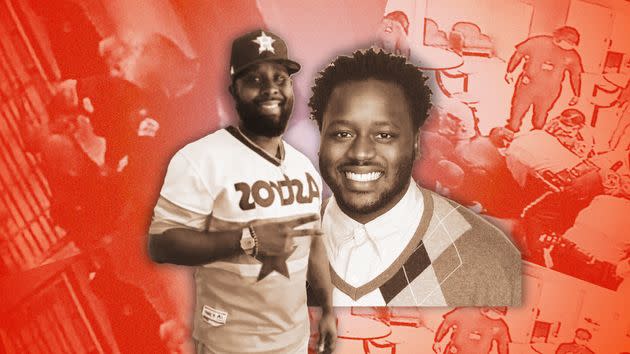

Two Black men, Gershun Freeman (left) and Irvo Otieno, were experiencing a mental health crisis before they died in police custody.

Gershun Freeman died inside a Memphis, Tennessee, jail in October. A few months later, in March, Irvo Otieno perished inside a state hospital shortly after police and hospital staff knelt on him for several minutes. Aside from being two more Black men in America who died in police custody, their stories share another commonality: Both found themselves under arrest by police officers during a mental health crisis.

On Oct. 5, 2022, Shelby County sheriff’s deputies opened Freeman’s cell inside the county jail. Freeman lunged toward the officers, who began to punch, kick, strike him with handcuffs,and pepper-spray him in an effort to subdue him, video footage shows. He died shortly after.

An autopsy conducted by a county medical examiner found Freeman died of exacerbation of heart disease due to the physical altercation and being subdued by officers, and classified the death as a homicide. In addition, Freeman had psychosis, a mental health condition that can cause people to perceive things differently than what is around them, his family has said.

Police had booked him four days earlier on aggravated kidnapping and aggravated assault charges following an incident with his girlfriend a week before his death, Shelby County court records show.

Freeman’s family and attorneys alleged corrections officers were too violent with someone suffering from a mental health emergency. “I don’t know what’s going on in America where law enforcement treats mental health issues like criminal issues,” civil rights attorney Benjamin Crump said during a press conference.

No charges have been filed against the guards, and there’s been no indication that any were reprimanded. Attorneys said at a recent press conference last week that all guards seen on camera are still working inside the Shelby County jail.

On March 3, Irvo Otieno was taken into custody because a neighbor called authorities alleging he was gathering lawn lights from a yard. Officers took him to a hospital for evaluation and then to jail, where they said he was “physically assaultive” to officers. (His family contests there was any dispute.)

Caroline Ouko makes remarks at the March 29 funeral for her son Irvo Otieno, killed by sheriff deputies and employees of Central State Hospital in Richmond, Virginia.

While handcuffed in custody at the hospital, video footage showed at least 10 Henrico County sheriff deputies and hospital staff kneeling on Otieno for 11 minutes. He became unresponsive and died on the floor on March 6. His death was a homicide due to asphyxiation, according to the state medical examiner’s office.

Seven officers from the Henrico County Sheriff’s office in Virginia and three hospital staff workers from that day have been charged with second-degree murder.

Otieno was diagnosed with bipolar and anxiety disorders during his teen years and had prior hospitalizations. However, according to his family’s attorneys, correctional officers deprived Otieno of his medication during his three days in jail.

The idea that law enforcement should not be involved in handling people experiencing a mental health crisis has grown following similar high-profile deaths in police custody.

“You cannot watch those videos and not think police and law enforcement are ill-equipped to respond to calls to help people in situations of crisis,” Daniela Gilbert, the director of the Vera Institute’s Redefining Public Safety program, told HuffPost. “It really continues to emphasize the need for a different approach to these kinds of situations, and more broadly, a different approach to public safety overall.”

Police reformers and experts argue that an officer’s presence increases the risks of an interaction turning violent ― even when the person never posed a threat. Likewise, experts told HuffPost disturbances, welfare checks, trespassing and other minor situations should not require law enforcement.

Gilbert says these calls, like minor traffic infractions, can often turn deadly due to implicit bias officers are holding.

“Our [American] culture of criminalization and use of aggressive policing and arrests as a primary tool for addressing social issues, all of that is rooted in a violent legacy of slavery and white supremacy. And it is inadequate and does not produce public safety,” Gilbert said.

“Tinkering around the edges of reform is not enough. Policing is embedded in the larger infrastructure of the criminal legal system.”

Civil rights attorney Ben Crump speaks during a news conference with the family of Gershun Freeman, a Black man whose death in custody at the Shelby County Jail in October 2022 has been classified as a homicide, in Memphis, Tennessee, on March 17.

In 2022, The Washington Post analyzed incidents between 2019 and 2021 where police were called for mental health or wellness checks — and found 178 cases where law enforcement killed the people they were called to help.

“There is no need for someone with a gun to respond to these situations when people really need someone who is better equipped to provide them with the help and resources they deserve,” Gilbert said.

In 2022, a total of 110 people were killed after police responded to someone “behaving erratically,” according to a study from Mapping Police Violence.

A recent report from the Treatment Advocacy Center found people with untreated mental illness were 16 times more likely to be killed by law enforcement.

Some areas have begun to reform how they handle mental health calls. For example, Denver began using social workers in some situations instead of police, and in 2021 New York Cityalso began to send social workers for some 911 calls.

In Washington, D.C., police started a pilot program that removes officers from some mental health calls and routes them instead toward city social workers.

Other cities like Portland established street response teams, specifically tasked with addressing people with mental health issues — and have faced success, according to researchers from Portland State University. The street response team operates unarmed weapons and is trained mainly to de-escalate encounters with civilians suffering from mental health issues.

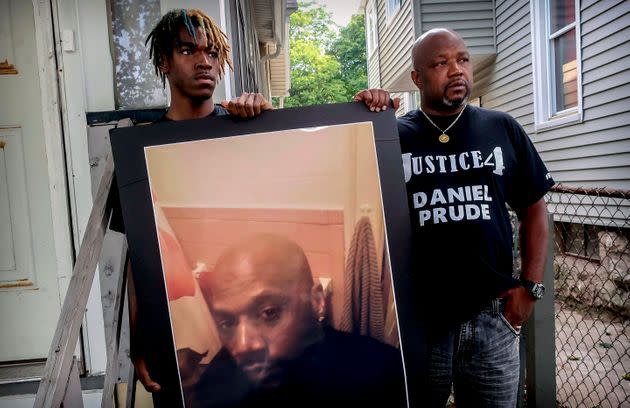

New York lawmakers proposed “Daniel’s Law” this year, which would create special civilian teams throughout the state who are trained in nonviolent response. It followed the March 2020 death of Daniel Prude, who was reportedly acting erratically before police in Rochester killed him.

Armin Prude (left) and Joe Prude hold an enlarged photo of Daniel Prude on Sept. 3, 2020. Daniel Prude died following a police encounter in Rochester, New York. City officials have agreed to pay $12 million to the family of Daniel Prude, a Black man who died after police held him down until he stopped breathing after encountering him running naked through the snowy streets of Rochester.

His brother said Prude experienced a mental health emergency after ingesting PCP and was naked in the street.

Prude’s family called 911, but things quickly turned violent after officers placed a “spit hood” over his head, a restraint device used to prevent people from spitting or biting. Prude was declared brain dead upon arriving at the hospital and died a few days later after being taken off life support. Prude was suicidal, according to his brother.

“There needs to be policy changes to make mental health care more affordable and a more diverse workforce of therapists to meet the need in our communities,” said Erlanger Taylor, an associate professor of psychology at Pepperdine University. “This may help to ensure that people can get help before it escalates to a crisis situation.”